Cruise the tables at antiquarian book fairs and the name Carolyn Wells is bound to catch your eye sooner or later, likely on a garish paperback with a title like The Radio Studio Murder or The Roll-Top Desk Mystery. Little known today, Wells wrote as many as 167 books, of which approximately 82 are mysteries, beginning at the turn of twentieth century and continuing into the early 1940s.

One of her most famous is Murder in the Bookshop (1936), which was revived by London’s Detective Club Crime Classics series in 2018 and will be available in the U.S. this month via HarperCollins. Featuring her beloved detective, Fleming Stone, who stars in 61 of her novels, its popularity probably has less to do with what Curtis Evans in the introduction to the new edition calls “the resurgence of popular interest in vintage mystery fiction,” and more to do with how well Wells knew this insular world. She was a die-hard book collector whose “outstanding” collection of early Walt Whitman editions was donated to the Library of Congress upon her death in 1942.

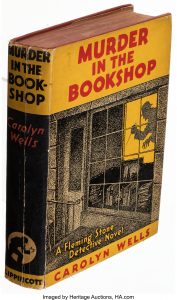

A first edition of Murder in the Bookshop in “fair” condition sold at auction this past December for $625. Courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

A first edition of Murder in the Bookshop in “fair” condition sold at auction this past December for $625. Courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

A delicious anecdote relayed by octogenarian book collector Edward Naumburg, Jr., in 1987 bears this out. He recalls a time in the early thirties when he visited At the Sign of the Sparrow, the rare bookshop of New York City’s Alfred Goldsmith, who happened at the time to be on the phone with Wells. She had called to ask about a good getaway technique for one of her characters. Goldsmith answered, “Let him jump out of the backroom window into the yard.” When he hung up, he boasted to his client that the author is writing a mystery about a bookshop, “and she’s visualizing this store for the killing.”

It wasn’t bluster. By that time, Wells and Goldsmith were old friends. When she decided, nearly two decades before, on a whim spurred by two collector friends, to expend her ample bank account buying rare Whitman editions, she relied on Goldsmith to guide her acquisitions. In her 1937 memoir, The Rest of My Life, she refers to book collecting as a “wild fancy” and breezily recounts buying two copies of every book she wanted, as well as signed copies, manuscripts, photos, letters, and postcards; she yearned for a lock of the poet’s hair, but never got one. “I know of no Whitman item that I do not possess,” she eventually concluded.

The 1855 first edition of Leaves of Grass, from the Carolyn Wells Houghton collection at the Library of Congress. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The 1855 first edition of Leaves of Grass, from the Carolyn Wells Houghton collection at the Library of Congress. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In 1922, the same year she published The Mystery Girl and The Vanishing of Betty Varian, Wells and Goldsmith co-authored A Concise Bibliography of the Works of Walt Whitman, With a Supplement of Fifty Books About Whitman. Wells preferred to call it a checklist, because it “lacks much of the minutiae a true bibliography should have.” In describing the basic physical attributes of nearly 100 copies of Leaves of Grass, there was still plenty of minutiae, though, e.g. the 1855 first edition is described: “Quarto. Green cloth. Blind-stamped, rustic lettered title, also triple-line border stamped in gilt on front and back covers. Backstrip shows lettering and ornaments gold stamped. Gilt edges. Marbled endpapers. Frontispiece portrait on plain paper. Author’s name in copyright notice on verso of title-page, and again on page 29….” Every item cited in this book went to the Library of Congress, including a signed copy of Whitman’s Memoranda During the War and Letters Written by Walt Whitman to his Mother from 1866 to 1872, of which only five copies are known to exist.

A paperback reprint of Wells’ The Radio Studio Murder. Courtesy of a private collection.

A paperback reprint of Wells’ The Radio Studio Murder. Courtesy of a private collection.

Wells knew keenly the mind of a collector. In Murder in the Bookshop, the first victim, a New Yorker named Philip Balfour, is smitten not by Whitman, but by Button Gwinnett, even now regarded as the rarest signatory to the Declaration of Independence. One evening, he urges his personal librarian to join him in visiting bookseller John Sewell, but when they arrive at the bookshop, it is closed. Nevertheless, they enter and browse the bookshelves, until the moment when the lights flicker out, and Balfour is stabbed with a foot-long silver skewer. The librarian, anesthetized by chloroform, is an unreliable witness, and soon enough becomes one of the main suspects. When it’s discovered that a $100,000-book signed by Gwinnett is also missing, the plot thickens.

Back at Balfour’s Park Avenue home, the police round up those who might be culpable: the librarian; the bookseller; the bookseller’s apprentice; Balfour’s much-younger wife, Alli, who also happens to be in love with the librarian; and Balfour’s louche son from his first marriage. The police are confounded, and Fleming Stone is called in to help, after which a second murder and a double abduction drive the story to its finale.

To the modern ear, the writing sounds a little wooden. However, as Margaret D. Stetz, professor of women’s studies and professor of humanities at the University of Delaware, points out, “the scene-setting in a high-end antiquarian bookstore, as well as in a private library in a New York mansion, is right on the money.”

The new reprint edition of Murder in the Bookshop was published by London’s Detective Club Crime Classics series. Courtesy of the publisher.

The new reprint edition of Murder in the Bookshop was published by London’s Detective Club Crime Classics series. Courtesy of the publisher.

Wells herself had a plush library inside her duplex on 67th St. overlooking Central Park. She had moved there after her marriage in 1918 to Hadwin Houghton at the age of 55. She remained there after his death just a year later, according to an obituary, “after a long illness,” at the age of 63—a fact that might strike some as suspicious given her line of work. How long of an illness? Houghton, who was not in his family’s publishing business, had been superintendent of a varnish manufacturing company. Her income plus what she inherited from him made her very wealthy, which bolstered her ability to surround herself with rare books.

Stetz, virtually the only scholar studying Wells, is publishing an article on her this spring in the Gazette of the Grolier Club, based on a talk she gave there in 2018. She prefers Wells’ comic writing to her mysteries. “If I had to pick a favorite book, it might be her viciously funny parody of Sinclair Lewis’ Main Street—Ptomaine Street. My gosh, she wasn’t afraid to be nasty!”

As Stetz notes, neither Wells’ book collecting nor her success as a writer should come as a surprise when one looks further into her history—the bits that can be pieced together from obituaries, old magazine articles, and her flighty memoir, that is. She got her professional start in life as the town librarian in suburban Rahway, New Jersey, a job she seemed to enjoy, and a trip with the American Library Association introduced her to several renowned institutional libraries. She deemed the Boston Athenaeum the “coziest place in the world to read.”

She began publishing in magazines in the early 1890s and parlayed that into books, young adult fiction and collections of nonsense verse. Inspired by the work of American detective novelist Anna Katherine Green, particularly Green’s 1897 novel That Affair Next Door (also to be reissued this month), she tried mysteries. The first Fleming Stone novel, The Clue, appeared in 1909, followed by The Gold Bag in 1911, and A Chain of Evidence in 1912. She became such an old hand at it by 1913 that she published The Technique of the Mystery Story, a writers’ guide to the genre.

Why then is she not better known? She had enormous commercial success; her Stone mysteries alone grossed $1 million by 1937, about $17 million today, according to Evans. When an anonymous writer in the Book Collector journal in 1984 posited that “the modern biblio-mystery seems to have originated in America,” he listed Wells among the select few originators.

Carolyn Wells’ bookplate, found within a first edition of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden that she once owned. In addition to Whitman, she liked to collect the “Concord poets” as she called them. Courtesy of a private collection.

Carolyn Wells’ bookplate, found within a first edition of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden that she once owned. In addition to Whitman, she liked to collect the “Concord poets” as she called them. Courtesy of a private collection.

Maybe she was overexposed. Wells’ literary output was indeed copious. Stetz thinks that could be part of the problem.

“There has always been a prejudice against women writers who have been defined as excessive and as overflowing some arbitrary boundaries: who allegedly have written too much, who have succeeded in too many categories, who have been too popular, who have made too much money, etc. Carolyn Wells was guilty of all of these so-called crimes, and she was marvelously unapologetic.”

Nevertheless, some of her books are collectible. Because of its special interest to fellow bibliomaniacs, Murder in the Bookshop is perhaps the most coveted of her books. Depending on its condition, a first edition in the original dust jacket can go for $500-$3,000—a legacy that would have pleased her.