For several months after I first watched Psycho as a teenager, I had difficulty sleeping. It wasn’t just the famous shower scene. It was the image of the Bates Motel in the darkness, Norman Bates’s demonic face, the claustrophobic interiors. Alfred Hitchcock deployed his command of the visual possibilities of cinema to produce an electrifying effect on his audience. His style might seem clichéd today, but that’s only because it’s been copied and riffed-on so often.

Hitchcock’s filmmaking career began in London during cinema’s silent era. His first credited film as director was Number 13 (1922), and his last—more than fifty features later—was 1976’s Family Plot. In between those, he directed suspense classics like The Thirty-Nine Steps (1935), Rebecca (1940), Shadow of A Doubt (1945), Rear Window (1954), To Catch a Thief (1955), and The Birds (1963). His thoughts on filmmaking are explained in a series of interviews conducted by Francois Truffaut and collected in Hitchcock, a volume that’s a must-read for film fans.

What makes Hitchcock’s films so memorable is the clarity and impact of his visual sequences. His best films often contain a single image, short sequence or repeating visual motif that encapsulate the dilemma of the main character or of the film as a whole. Hitchcock wanted nothing to detract from the audience’s experience of suspense, and strove to keep his visuals as clear as possible. “I’ve often found that a suspense situation is weakened because the action is not sufficiently clear,” he explained to Truffaut. “For instance, if two actors should happen to be wearing similar suits, the viewer can’t tell one from the other… and if a crucial scene unfolds while he is trying to figure these things out, its emotional impact is dissipated. So it’s important to be explicit, to clarify constantly.”

Here, in chronological order are some obvious, and also less well-known but equally compelling, examples of Hitchcock’s visual storytelling and gripping suspense creation.

Suspicion (1941)

Joan Fontaine plays a young bride who suspects that her debonair husband, played by Cary Grant, is plotting to kill her. In a particularly striking sequence, Grant walks up the staircase carrying a glass of milk on a tray for his wife who is in bed. The viewer, like the character played by Fontaine, fears that the milk might be poisoned. The film keeps the viewer and Fontaine on edge about whether Grant’s behavior is truly sinister. To convey the fear in Fontaine’s mind without resorting to dialogue or close-ups of the glass, Hitchcock films Grant in the shadows and lights the glass from inside so that it’s luminous. He tells Truffaut: “I put a light right inside the glass… Cary Grant’s walking up the stairs and everyone’s attention had to be focused on the glass.” The implications for the viewer couldn’t be clearer.

Strangers on a Train (1951)

Based on the novel by Patricia Highsmith, Strangers On A Train tells the story of what happens when a psychopath, Bruno Anthony (Robert Walker), offers to “trade murders” with an unsuspecting tennis player, Guy Haines (Farley Granger). The opening credits—two sets of footsteps arriving at a train station and walking in different directions until they finally bump into each other—is a clever Hitchcock touch and neatly encapsulates the film’s premise of two lives that collide seemingly by accident. The climactic sequence on a an out-control carousel is also unforgettable. But the murder of Guy’s wife, filmed from the perspective of its reflection in the female victim’s fallen spectacles, perfectly captures the film’s themes of distorted doubles and the undesirability of women with minds of their own. (Women and glasses come up again later in the film to trip up Bruno.)

Vertigo (1958)

Another story about doubles, this time with an added fear of falling and obsession with a woman who never existed. The camera lingers on Kim Novak’s spiral hairdo, which mirrors the spiral hairdo in a portrait that Novak’s character spends a fair amount of time gazing at, which mirrors the images of the abyss or unknown (flight of stairs in the cathedral) that Jimmy Stewart if so afraid of falling into. Spiraling out of control is one of Vertigo’s central preoccupations, and it’s not-so-plausible plot takes on an eerie and unsettling resonance precisely because of Hitchcock’s use of strong and repeating visual imagery.

North By Northwest (1959)

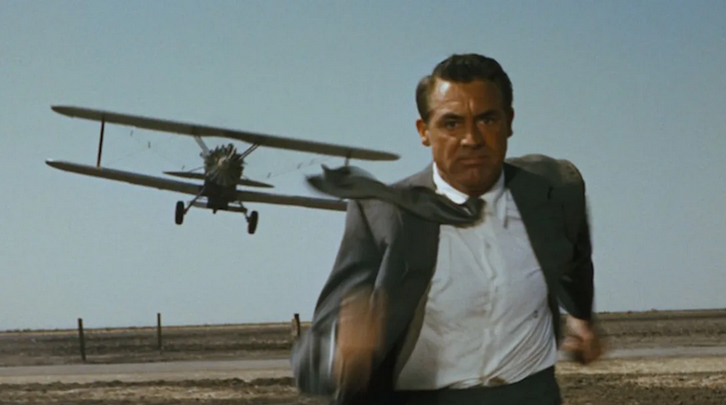

Cary Grant chased through cornfields by a crop duster is such an iconic image that it seems to exist outside the film in which it occurs. The sequence transcends the narrative of North By Northwest by perfectly dramatizing the terror of being chased by a nameless, faceless threat with nowhere and no one to turn to.

Hitchcock explains the manner in which he stretched out time to build up the suspense of the moment. If the scene had been filmed to show the way it was experienced by Grant’s character, it would be finished in an instant. Instead, Hitchcock stretches it over several minutes, during which he shows the barren, flat landscape and the vast distances involved, so that the viewer can see and fully appreciate that there is nowhere for Grant’s character to take cover. He also shows the crop duster before Grant’s character would have noticed it.

“This kind of scene can’t be wholly subjective [from Grant’s point of view] because it would go by in a flash,” Hitchcock told Truffaut. “It’s necessary to show the approaching plane, even before Cary Grant spots it, because if the shot is too fast, the plane is in and out of the frame too quickly for the viewer to realize what’s happening… You deliberately abandon the subjective angle and go to an objective viewpoint… so that that the audience might be fully aware of what is happening. [We have to] prepare the public for the threat of a plane dive.”

Psycho (1960)

Hand. Knife. Shower curtain. We know which film this is without having to be told. Hitchcock famously explained the distinction between surprise and suspense. Surprise, he says, is when a bomb goes off without warning. Suspense is when the public knows that the bomb has been placed and is waiting for it to go off.

“In the first case we have given the public fifteen seconds of surprise…” he tells Truffaut. “In the second case we have provided them with fifteen minutes of suspense.” Clearly, Hitchcock usually prefers the latter. But in Psycho, the audience is given the surprise of Janet Leigh, who appears to be the main character, being killed without warning, very early on in the film, and in an extremely violent manner. Unlike the scene in North By Northwest in which time is drawn out to create suspense and which consists of several long takes, here the scene is choppy: it required seventy camera set-ups but plays for just about 45 seconds. For Hitchcock, the satisfaction comes from using cinematic techniques to generate an emotional response from his audience. “I feel it’s tremendously satisfying for us to be able to use the cinematic art to achieve something of a mass emotion. And with Psycho we most definitely achieved this. It wasn’t a message that stirred the audiences, nor was it a great performance… They were aroused by pure film.”