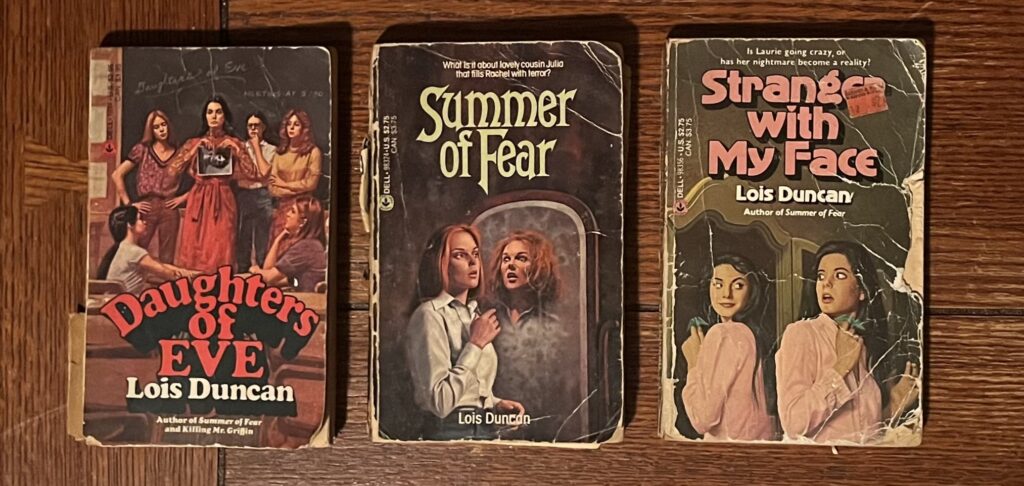

I still own three of Lois Duncan’s books. Growing up, I read so many, but these are the three I have left: Daughters of Eve, Stranger with My Face, and Summer of Fear. The covers are creased and falling apart, and the pages are so fragile that they tear when I try to turn them, but each book burns as relevantly and brightly as when they were glossy and new and first belonged to me.

The prolific Duncan practiced her craft in various genres, including children’s books, poetry, and non-fiction (two of her books are about her daughter Kaitlyn’s 1989 murder, which went unsolved for the duration of Duncan’s life). But beginning in the early 1960s, she wrote horror and suspense novels for teens—and never pulled any of the punches that might be expected of a “young adult author.”

Duncan was not precious. She was precise. She excelled at identifying the traumatic aspects of being a teenage girl, writing about topics such as eating disorders, popularity, sex, domestic violence, suicide, authority, dating, and unplanned pregnancy, just to name a few, and amplifying the horror of each one into full-blown nightmares—which, come to think of it now, was comforting to me as a developing young woman. It meant she was a writer who took teenage girls seriously. She felt our pain.

Take Locked in Time (1985) as an example, in which petulant teenager Josie is magically, permanently paused in mid-adolescence by her mother, who wishes to remain eternally young. Unfortunately, the cessation of the aging process comes at the worst, most awkward point possible for Josie. She is on the cusp of becoming her adult, autonomous self, and must endure acne, mood swings, and a body and self that will remain undeveloped until the end of time. It’s an excruciating fate, but Duncan knew—as evidenced in many of her books, particularly the three that I still own—that Josie’s fate was a version of purgatory, and the transition from teenage girl to woman is the true hellscape, a perilous and potential never-ending journey that pits our true selves against the women the world wants us to be.

After all, when we are growing up, we wonder who we will become. How much of our early selves will remain within us when we are adults? How will we flourish, where will we fail, and what will we be expected to “get over”? Lois Duncan seemed to map it all out, her books creating a nightmarish “Choose Your Own Adventure” series in which the pitfalls of growing up are always life or death. The difficult decisions belong to us, if only we can make out our options clearly—and then fight like hell to be able to make those choices.

Daughters of Eve (1979) sets a group of teenage girls on their life course with the cutting precision of a razorblade. Set in a small Michigan suburb called Modesta, it tells the story of nine high schoolers—Ann, Tammy, Kelly, Holly, Paula, Bambi, Ruth, Laura, and Jane—in varying degrees of thrall to teacher Irene, who is the leader of their exclusive after-school club Daughters of Eve. The club focuses at first on extracurricular activities such as selling raffle tickets to raise money for an all-girl soccer team. But when popular boy Peter’s cruelty leads to a vulnerable member’s suicide attempt, the Daughters of Eve join together under Irene’s leadership for a different kind of activity: ambushing Peter in the woods, holding him down, binding his throat so he can barely breathe, and shaving his head, all the while laughing and jeering at him as he’s being frightened nearly to death. The act renders him homebound for the rest of the school year and, in the context of his former life as big man on campus, effectively impotent. From that point on, the girls in the book will decide one by one where they stand—and if they will fight—in a world populated by cruel, incompetent men and the women they have broken.

The abrupt, devastating ending—in which Jane, one of the members, commits an act of murder both as a release from a future spent serving her violent, abusive father and to protect Irene from discovery—is followed by a brief epilogue. For the Record (three years later) updates, in chillingly neutral language, the status of each girl; who went to college, who stayed home to become a housewife (Irene’s idea of a decision equivalent to death), and which one is “a patient at the State Mental Hospital in Ypsilanti, Michigan.” The end seems to pose the question to the reader: who will you decide to be?

1981’s Stranger with My Face supplies some important data to help you answer that question. The cover depicts a conflicting mirror image: a young woman with long black hair and a pink blouse holds a turquoise bird figurine and looks over her shoulder at her reflection in a mirror, which looks back at her with a knowing smirk that most certainly does not match the other girl’s frightened expression.

The book tells the story of Laurie, a teenager who lives with her family on an island off the coast of New England. Through her apparent doppelganger, Laurie finds out that not only is she adopted, but that she had a twin sister named Lia who was so obviously evil even as a baby that Laurie’s adoptive parents decided to bring only Laurie home, leaving Lia behind.

“It seemed wrong to separate twin sisters,” Laurie’s mother recalls about the unorthodox adoption process. “I picked you up and cuddled you, and I knew I never wanted to let you go. Then I… picked up the other baby… I wanted to put her down…. She felt alien in my arms… I knew I would not be able to love her.”

Unfortunately for Laurie and her family, the “alien” baby grows up to be evil and an expert in the art of astral projection. It is Lia who appears as Laurie’s doppelganger—a reflection who does not obey the girl looking in the mirror—to tell her the truth about her family.

Laurie has now learned in an instant what it takes many children years to slowly absorb (and then discuss in therapy): that they are loved when they are “good,” and not when they are “bad.” Laurie’s mother was just laying it all out there on the table by explaining that she held the identical babies and perceived one to be “alien,” so she left her behind, while adopting the “cuddly” baby and giving her a life of unending emotional and material riches. I feel like even if Lia wasn’t “bad” as a baby (which is an impossibility in real life anyway), she sure as shit became vengeful when she figured out what happened to her!

Throughout the book, the theme of a “good Laurie” and a “bad Laurie” persists, as no one believes in Laurie’s story that Lia’s astral projection is real, present, and causing serious problems that range from broken relationships to near-fatal “accidents.” But the story skews closer to reality if there really is only one “Laurie” (as opposed to “Laurie and Lia”). Lois Duncan’s persistent theme throughout her books of “You’ve changed”—from parent to child, friend to friend, sibling to sibling—is evident more than ever in Stranger with My Face. Laurie is growing up on an island, literally. She becomes emotionally estranged from her family and friends and drawn to outsider Jeff, who is badly disfigured from a terrible accident that left half his face burned beyond recognition. The people who were close to her see her as having become a completely different person. And who hasn’t felt that way about themselves during life transitions, whether it’s from child to teenager, teenager to adult, or an innocent-turned-trauma survivor? All of these transitions leave us “changed.” Do we really have to turn our backs on our “changed” selves in order to be loved? According to Stranger with My Face, the answer seems to be yes, making it a very effective horror novel indeed.

Summer of Fear (1976) was the first Lois Duncan book I ever read. My friend had received it as a gift and showed it to me at a sleepover. The cover depicted a pretty redheaded girl looking anxiously at the warped, feral reflection that stares back at her with wild eyes and a mouth curled up in a snarl. The cover scared us so much that we turned it face-down so it wouldn’t “look at us” overnight. The next morning, my friend told me to take it because she didn’t want it in her room anymore. It’s the same copy I still have, over three decades later.

In Summer of Fear, teenager Rachel has her life turned upside down when her aunt and uncle are killed in a fiery car accident and their daughter, Julia, comes to live with Rachel’s family. The enigmatic Julia turns out to be a witch from the Ozarks who tears apart Rachel’s life piece by piece. She renders Rachel unable to attend a dance by giving her a terrible case of hives, steals the attention—and loyalty—of Rachel’s brother, seduces Rachel’s boyfriend, kills Rachel’s dog, and finally goes in for the ultimate kill, planning to murder Rachel’s mother and marry Rachel’s father. Because of this, or manifested by it, Rachel fears womanhood: what it might hold for her, and whether any of her carefree, gilded childhood will remain. The hives that Julia sics on Rachel make her unrecognizable when she looks in the mirror: The face that looked back at me was not my own, Duncan writes. It was a grotesque mask, bloated and red and patchy.

My experiences with Lois Duncan’s books began in childhood and immediately became meaningful, so it’s been important to me to preserve my own insights and feelings about her work. I have not sought out other interpretations of her novels, and I don’t know what Summer of Fear represents to other people. I only know that for me, Julia’s arrival and subsequent stay with Rachel’s family is a perfectly crafted description of trauma. It could be about a traumatic incident or relationship, or simply the extreme emotional dissonance of becoming a woman, or both. Either way, it accurately depicts how a trauma survivor’s notions of safety have been scattered to the winds, their new consciousness left standing like a blown-out building in the wake of a natural disaster.

óAs a child of divorced parents, I wonder if the fiery end met by Julia’s parents represents divorce, and that perhaps Julia is a stand-in for a stepparent who takes over as the most important person in the lives of the men Rachel depends on—her brother, boyfriend, and father—who are all shown to be at the mercy of Julia’s womanly, sexual energy. Rachel’s sweet puppy, Trickle, an obvious symbol of her early life’s happiness, dies a slow, miserable, isolated death—which is exactly how some people feel about their own childhoods when their growing up process is interrupted by trauma. The happy ending of Summer of Fear reads less like closure and more like the kind of dreamlike state one falls into after sobbing oneself to sleep, with Julia out in the world presumably wreaking havoc on new victims and Rachel embarking on her adulthood. Once again it is summer. Golden summer, muses Rachel four years later, now a college student, back with her former boyfriend, and whistling for the new dog she has named Lucky.

Take all the luck you can, Rachel. You’re gonna need it.

***