The snow continued for a week, stopping even the mail and the telegram service. The snow just kept falling and somewhere south of them the Cornelia Lawrence was still sitting in the shipyard. Watching their savings diminish, Joshua Patten was growing impatient and a little worried.

Then, in the spring of 1854, a new opportunity popped up unexpectedly. Captain Patten was offered the temporary command of the Flying Scud, a 220-foot-long extreme clipper that had launched in Damariscotta, Maine, on November 2, 1853. There was a gap in the ship’s schedule. The next fall, she was destined to be put in the service of an emigrant packet line from New York to Australia.

Damariscotta is not twenty-five miles from Rockland, and this was the Flying Scud’s maiden voyage. Joshua would finally have his chance to earn the kind of hard-sailing reputation that by summer would launch him into the fast-paced and dangerous world of international extreme clipper deliveries as an up-and-comer.

It was thanks to a dramatic impromptu race against the celebrated master Captain Samuel Samuels that had the sea captains and ship’s owners talking.

Clipper ships, especially the so-called extreme clippers like the Flying Scud, were marvels of engineering, but, like performance race cars, they were built for power and speed, not safety. The 1850s were the golden age of these astonishing sailing vessels, and the captains who sailed them hardest and fastest were international celebrities. A clipper could travel at previously unimaginable speeds and cut days or even weeks off the long sea voyages that integrated trade in a global economy. They were, if you will, the “just-in-time” portion of the nineteenth-century supply chain, the expedited couriers of the 1850s. When it had to be there and fast, it had to be clipper.

___________________________________

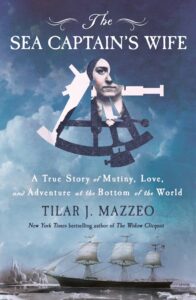

From The Sea Captain’s Wife: A True Story of Mutiny, Love, and Adventure at the Bottom of the World by Tilar J. Mazzeo Copyright © 2025 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

___________________________________

Speed cost, but it also paid. Speed paid off for the shipowners and the cargo owners, who charged a premium for the clipper service, and it paid for the captains, who were rewarded for delivering results. A sea captain who could transport goods and passengers from New York to San Francisco in under one hundred days could generally count on a salary of $3,000 plus a bonus of several thousand dollars more, for a total compensation, in modern terms, of over $200,000. A captain ferrying passengers could generally double that amount with the receipts for passage. It was a fine wage, easily twice what Joshua could earn as a coastal captain on the run between Rockland and Boston.

But the salary was not how clipper captains became fabulously wealthy. The real money came from fast international cargo transport.

The extreme clippers were large ships, anywhere from 150 to nearly 300 feet long; 200 feet from bow to stern was common. They were three-, four-, sometimes five-masted ships, rigged tall and square, with gleaming black hulls and bright, copper bottoms, and carrying ten thousand square feet or more of canvas sail, controlled by a complex system of lines. “Learning the ropes” to qualify as an able seaman was no metaphor. The Flying Scud flew seventeen sails. Ambitious young captains used every inch of those sails to press for speed, reducing the canvas only when the wind’s power was too great to manage. Sometimes, captains didn’t reef their sails even then, with occasionally fatal consequences. For these were also narrow boats, with sharp lines, designed to cut swiftly through the water, generally overpowered and often under-ballasted.

The evolution of the clipper was largely due to American and then, later, British innovation and to the intense mercantile competition between the empire and her former colony. From the early use of the nimble Baltimore-built clippers that ran the British blockades during the War of 1812 and the opium clippers that smuggled narcotics in and out of China, to the innovation of the “extreme” clippers after 1845 that Joshua was sailing and that raced to bring the spring tea harvests to New York and London markets, it was always about speed and lucrative cargo.

But the height of the clipper ship era began in 1848, the same year that South Thomaston became a town, with the discovery of gold in far-off California. The wealth of one fueled the prosperity of the other.

The transcontinental railroad did not yet exist. Neither did the canal in Panama. Slow and sturdy frigates were not fit for purpose when there was a frantic race to move mining equipment and eager young men to the other side of a continent in a hurry. There were fortunes to be made; prospectors rushed to get their claim in early. When gold was discovered next in Australia in 1851, the push to build clippers only accelerated.

The public was fascinated by the stories of extreme maritime adventure aboard the clippers, and passengers’ journals of these voyages to California or Australia were often collected and published in volumes of thrilling sea stories. One such nineteenth-century volume recounted for an eager reading public a storm at sea aboard the clipper the Sagamore. “Tacking a large square-rigged vessel is considerable of a job at any time, but at night, and in a hurricane, it is an arduous task,” one unfortunate passenger reported:

“The stiffened braces, wet with icy salt water, got tangled up, and occasionally a man would make a mistake amid the maze of ropes . . . Several times [the ship] went over so far that captain and mates hardly dared to breathe for fear she was on her side and would never right . . . At each roll, the bulwarks went far under, allowing a flood to come roaring and tumbling aboard; washing about the main deck, tangling up ropes, and knocking men off their feet.”

A ship’s boy was not a seaman until he had survived at least three or four offshore voyages. Survival was not assured: A full 75 percent of the ship’s logs from this period record the death at sea of at least one crew member.

Speed did not pay for the crew in these circumstances. Crews and captains had competing objectives. Sailing conservatively in foul weather, even if the ship lost speed by it, was safer for a sailor. Men were lost at sea all the time by falling from a mast or being knocked off their feet and off the decks, and few could swim well enough to tread water for long. There was no easy way to turn a ship around, no way to save them in time. Besides: Crew were paid by the month. Captains, on the other hand, had every incentive, especially in the clipper trade, to push their crew to the limit.

Merchant sailing ships were not floating democracies. At sea, a captain’s power was nearly unfettered. He was the master. He alone chose where they would sail, under what sail power, and at what risk to the ship and the crew. A seaman’s contract was binding; there was no quitting in some distant port to find another vessel. A man who breached his shipping articles was a deserter and subject to arrest or forced return to a disgruntled captain. The captain had the authority to discipline any crew member who disobeyed his orders; a sailor wanted, if he could, to choose his captain carefully because there were “bully captains” who flogged sailors on sea voyages for minor infractions.

Life onboard was strictly divided along the lines of this hierarchy. The seamen—and on a clipper ship they might number thirty, forty, or even fifty or more, from as young as fourteen or fifteen to someone like the forty-year-old seaman George Brown in 1850—lived and passed their free time “before the mast,” literally in the area of the ship known as the forecastle or “fo’scle.” Here, a captain did not enter.

Generally located between the first and the second mast of a three-masted clipper, the forecastle was a raised utilitarian bunkhouse, built on deck, forward of the main hatch, with a galley at one end, the ship’s carpenter’s room at the other end, a long mess table down the center, and tightly stacked bunks on all sides of the mess table. A seaman who wished to relieve himself faced a trudge to the bow or the bucket, and relieving oneself on a pitching vessel at night required some agility. Even today, more than one unlucky sailor has pitched overboard taking a nighttime pee, and grog generally does not help matters. Privacy was not a seaman’s lot, and neither was regular bathing.

The quarters occupied by the captain, his senior officers, any genteel paying passengers, and the agent of the ship’s owners were located at the rear of the ship. Life at sea was never easy, but the conditions here were very different. A sea captain and his officers were not working-class mariners. The captain was a gentleman, waited upon by a steward, and his authority rested as much on maintaining a strict class separation from his crew as from meting out physical discipline. The men who commanded the fastest clippers had an international celebrity that today is almost unfathomable. They were the rock stars and elite athletes of the mid-nineteenth century. No member of the crew was permitted even to address the captain unbidden.

At the aft of the ship, the captain’s quarters were also a raised bunkhouse stepped up above deck, but the proportions were entirely different. Where the roof of the forecastle was often used for lifeboat storage, the captain’s quarters could be two stories high, with banks of leaded glass windows providing floods of natural light, spaces that often looked, more than anything, like the interior of a small and particularly beautiful chapel. On the top of the captain’s quarters was the “poop deck,” where the captain scanned the horizon and took navigational sightings. In the center of the main saloon was a large and spacious captain’s table that opened onto the captain’s office, where he kept the ship’s library and the chartroom. To one side were the captain’s personal suite of rooms, with a bedroom, private sitting room, and facilities, and ranged around the open dining room were staterooms for the first mate, the ship’s agents, and any paying passengers. The 180-foot tea clipper Foochow had a half dozen additional staterooms and was probably typical.

The wine at captain’s table was good, and the suite of staterooms at the aft of a clipper were luxurious. The storeroom and armory were both accessed through the captain’s quarters, which also served as a kind of shipboard fortress in the event of mutiny or pirates. Polished wood gleamed in the saloon and master’s stateroom (though the officers’ cabins were small and spartan), and cozy fires burned in front of rich oriental carpets and other luxurious souvenirs of a captain’s far-flung voyages. The Witch of the Wave, a clipper built in 1851 for the trade, was recorded as boasting “interiors of bird’s eye maple . . . enameled cornices edged with gold [and] dark imitation marble pedestals.” One sea captain’s wife, Hannah Rebecca Burgess, writing in the same winter that Captain Patten commanded the Flying Scud to Liverpool, recorded in her journal that the staterooms aboard the clipper Whirlwind boasted a dining room “painted with Zinc paint of a cream color . . . beautifully ornamented with gilded work,” a parlor “of Mahogany, rosewood, and satin wood,” and a suite of staterooms for the captain and officers “carpeted with nice velvet tapestry.”

Aboard a clipper were, notably, no women unless the captain’s wife sailed with the ship or the captain took aboard paying female passengers. Joshua sailed the Flying Scud that winter solo. His time commanding emigrant packets had taught Joshua to dislike taking passengers, especially ladies. He much preferred to fill his staterooms with additional cargo.

The Flying Scud would sail from New York. Mary Ann remained in Boston during Joshua’s absence.

___________________________________

From The Sea Captain’s Wife: A True Story of Mutiny, Love, and Adventure at the Bottom of the World by Tilar J. Mazzeo Copyright © 2025 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.