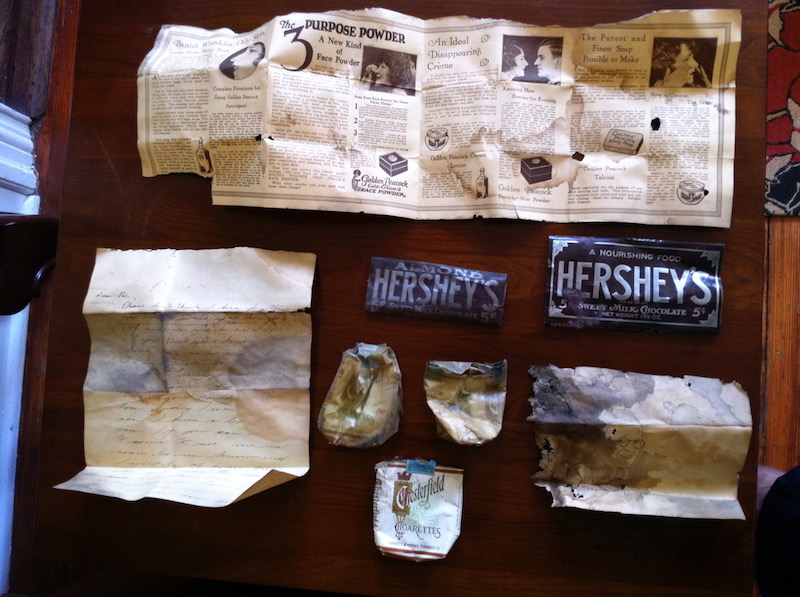

Several years ago, I decided to redecorate my office. The idea was to make it more aesthetically conducive to writing: fresh paint in pleasing earth tones, new furniture made from recycled pallet wood, everywhere clean, modern surfaces—a blank canvas from which to create. In truth, it was an elaborate (and expensive) excuse to procrastinate revising the ending of my novel, Dodging and Burning. One Saturday, passionately avoiding my laptop, I grabbed my husband, and we moved the furniture out and ripped up the frayed wall-to-wall Berber carpeting. Underneath, we discovered a loose board in the pine flooring. Our curiosity piqued, we removed it. Between the support beams, peeking through the dust, we found a treasure trove: three Chesterfield cigarette packets, two Hershey bar wrappers, an ad for women’s cosmetics, a hand-drawing (perhaps a tracing) of the silent film comedian Harold Lloyd, and the remains of a letter penned by a woman named Catherine, all dating back to the 1920’s or early 1930’s.

Located on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, our townhouse was constructed in 1901, and for nearly thirty years, it served as a women’s boarding house, a fact I discovered when applying for a business license to rent out the basement apartment. The building has retained most of its original Victorian floor plan, the top two floors compartmentalized like a dormitory. My office, in a nook on the third floor, could’ve have served as a small bedroom, the tight quarters only mitigated by a tall window overlooking East Capitol Street.

As a mystery writer, I live for this sort of thing. Finding tangible evidence from a life lived during the 1920’s or 30’s, especially fragments not orchestrated for posterity, is food for the imagination. After cleaning off the dust and inspecting the artifacts, I transcribed Catherine’s partially disintegrated letter:

Dear Pal,

Please don’t think I have forgotten you I only wish you thought of me as much as I do of you. But you know everything is with … it is quite unfors … me … to see you … then I do … wish you could … how badly I want … you I have a lot … you. If you can a … to come to see me real soon let me know and I will be at home any day you say. The weather have has been very hot and sulky here we haven’t … any rain for nearly three … so you know how hot … I went to the movies and saw dancing sweeties. I mean it was a really hot picture. I just wish you could see me now. It is 3:00 AM and I still have my night gown … I haven’t even combed my hair … writing this letter with … me and I got ink all … night gown and leg. Some … [a]sk?) We were Chapel … s Sunday. W… the water … stagesant [stagnant?] do to hot weather … [wou]ldn’t allow you to take any showers on account of the shortage of water. For there hadn’t been any rain for a long while. Gee it surly is lonesome here all day with nothing to do … time I realy hate my self … answer soon as I want … from you— Catherine

Article continues after advertisement

Who is Catherine? Who is the “Pal”? Did Catherine live in my office, or was it the letter’s recipient? She must have loved Hershey’s bars and Chesterfield’s. But why keep the wrappers? Was smoking forbidden in the house? Was she sneaking cigarettes and blowing the smoke out the window? Perhaps the chocolate bars were an indulgence she didn’t want to share. Why did she keep a doodle of Harold Lloyd? Why hang on to a cosmetics ad? And what is the true nature of this letter after all? Is it correspondence between friends or lovers? There’s no reason why Pal couldn’t have been a woman, right? One thing is certain, Catherine missed this person and felt insecure about their relationship: “I only wish you thought of me as much as I do you.” There is irrefutable residue of her emotion.

Like the letter itself, the lives of these women are full of ellipses, but the ellipses intrigue. We can dream a story to life. Maybe Catherine was in a lesbian relationship. Maybe her lover was married and couldn’t get away. Maybe they first met at the cinema, sitting next to each other, each an enthusiastic fan of Harold Lloyd. Maybe just this once Catherine decided she’d share her Hershey’s bar. Or maybe the other woman bummed a cigarette from Catherine on their way out of the theater and they struck up a conversation.

***

All fiction writers begin with fragments—a moment of insight, the memory of an experience. Through writing, we try to make sense of these fragments. Mystery writers bring this endeavor to the surface of the story. The detective is deliberate about it. Whether amateur or professional, Miss Marple or Harry Bosch, this protagonist considers it his or her job to uncover the truth. In traditional puzzle mysteries, such as Agatha Christie’s, the detective’s role is to restore order to a community after a crime has disrupted the status quo and brought about instability. The detective must arrange those fragments to unlock the truth, unveil the culprit, and return the world to an orderly state. These stories are enthralling and satisfying, but they rarely describe what we experience in life. So often, like my experience discovering the Catherine’s keepsakes, we want to make sense of the fragments, but don’t have the adequate information to do so.

All fiction writers begin with fragments—a moment of insight, the memory of an experience. Through writing, we try to make sense of these fragments. Mystery writers bring this endeavor to the surface of the story.Several contemporary writers have structured novels that both satisfy the desire for closure in a reader and challenge the notion that a tidy resolution is always inevitable. In Laura Lippman’s After I’m Gone, a father of three vanishes to avoid a fifteen-year prison sentence for mail fraud, leaving his family to pick up the pieces. By the end of the novel, the reader knows what happened to the father, but many of the characters don’t. The reader receives the emotional closure, but in the world of the story, much like that of life, loose ends remain. Val McDermid takes this strategy a step further. In her novel, Place of Execution, a girl goes missing in 1963, and a man is arrested for the crime. Even though no body is found, he is sentenced and executed. In the 90’s, a journalist digs up the past, discovering that the original arrangement of the facts was shockingly incorrect. Both the original story and the revised story have dire consequences. In the first, a community is shattered and then reassembled. Closure comes in the form of an execution. In the second, the detective who got it wrong is broken, and McDermid leaves us with the question: Is it better to tell the truth and throw a community into upheaval, or preserve the lie and maintain order?

I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, Michelle McNamara’s true crime memoir, chronicles her dogged, yet unresolved, investigation into the notorious Golden State Killer. Before McNamara could finish the book, she died suddenly, leaving her husband and editors to piece together the book with no definitive unveiling of the notorious serial rapist and murderer. Although not as assuring as fiction, it speaks most directly to lived experience: we all have mysteries in our lives that resist resolution and haunt us. In the face of fragments, Ian McEwan’s Atonement shows us yet another possibility. Although not marketed as a mystery, the novel centers around a crime and its fallout, specifically a false accusation. Thirteen-year-old Briony Tallis accuses her older sister’s lover of rape, a lie which has heartbreaking consequences. By its end, Briony, now an elderly woman and a renowned novelist, offers an alternate history, a fictional resolution, to her story to atone for her childhood offense. In the absence of satisfying resolution, McEwan suggests, we must create our own closure by telling the story as it should have ended.

Perhaps that’s why we continue to read traditional mystery fiction: Time and again, these stories give us satisfying narratives we can turn to in a world full of inconclusive evidence.Perhaps that’s why we continue to read traditional mystery fiction: Time and again, these stories give us satisfying narratives we can turn to in a world full of inconclusive evidence. Of course, some crime writers, such as Lippman and McDermid, wish to level with reality and depart from a wholly comforting narrative. Others, like McNamara, have no choice but leave questions unresolved. McEwan in Atonement takes a more metafictional approach. Within the novel, the act of storytelling brings about resolution even though it’s a fabrication. Narratives, regardless of their inherent truth, have the power to offer emotional closure.

***

Set during WWII, my novel, Dodging and Burning, is the story of the youthful romance between two gay men, Jay and Robbie, and the horrible murder that tears them apart. Two women, one a society girl and the other a tomboy, share the telling of the story, each loving the men in different ways. I was pleased with my draft, but something still wasn’t right about the ending, hence my plunge into redecorating. My narrators searched for closure through the clues about Jay and Robbie, much as I tried to make sense of the keepsakes under my floorboards, but the conclusion felt too pat, too neat.

As I dove in to the revision, I channeled my own desire to uncover a good story about Catherine’s letter and the other mementos. I would never know the truth, but the act of finding a story in the fragments brought meaning to my life and resonated with my novel. I then understood that my narrators needed to tell different versions of the same story, that they weren’t seeking one truth, but separate truths. Like McEwan’s elderly Briony, they must arrive at closure through an imaginative gesture; they must dream up the ending they need to make sense of the world.