In the mid-1970s, the CIA and KGB were both watching Karel Koecher closely–and they were both convinced he was working for the enemy. They were both right.

___________________________________

In September 1944, the first units of the Red Army crossed into Eastern Slovakia. On May 5, 1945, with the Red Army on the outskirts of the city, the Prague uprising began. The next day, sixty miles west, US general George Patton’s Third Army liberated the city of Plzeň and its famed Pilsner Urquell brewery. After quaffing a celebratory pivo or two, Patton and company halted their advance eighteen miles short of Prague before retreating back across the German border. The victorious allies had allocated Czechoslovakia to the Soviet zone of occupation, and for many in Czechoslovakia, the word Yalta—the location of the February 1945 conference that outlined the postwar occupation plans—joined Munich as shorthand for betrayal.

The first Russians into Prague were led by General Andrei Vlasov. Earlier in the war, his units—a ragtag bunch of right-wingers, ex-czarist aristocracy, and veterans of the White Army that had battled and lost to the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War—had sided with the Nazis to fight against the Red Army. Once it became clear the Nazis would lose, the “Vlasovci,” as they are known in Czech, switched sides. Hoping to surrender to the Americans rather than the Soviets, the Vlasovci turned their guns back on the Germans and fought their way west. For Vlasov at least, the plan failed. He was captured by the Soviets, transferred to Moscow, and executed. But a good number of soldiers from this rogue unit survived, fled to the United States, and found employment with the CIA—where Russian speakers who hated reds were always in high demand. Karel and the Vlasovci would meet again some three decades hence.

In April 1945, a provisional Czechoslovak government passed a law revoking citizenship for all ethnic Germans and Hungarians. Nine of the twenty-five ministers in that government were members of the Communist Party, but that ratio was about to change. At the time of liberation, the Czechoslovak Communist Party had just fifty thousand members, but eleven months later, there were more than 1.2 million members. By 1948, the party counted 2.5 million acolytes—one of every three adults.

Starting in June 1945, people’s courts tried alleged Nazi collaborators—97 percent of the accused were convicted. More than 660,000 ethnic Germans were removed from the country in the first burst of an ethnic cleansing orgy. A further 20,000 were executed. In August 1945, the Beneš Decrees, named after the reinstalled president, codified the earlier law stripping Germans and Hungarians of citizenship. During 1946, 2.8 million more ethnic Germans were forcibly removed from Czechoslovakia. Property in the Sudetenland, now returned to Czechoslovakia, was seized from ethnic Germans and collaborators. Accounting for one-quarter of the national wealth, it was turned over to 1.5 million ethnic Slavs who were brought in from elsewhere in the country.

***

In the autumn of 1945, eleven-year-old Karel, by now speaking English “more or less fluently,” was one of many enduring postwar hardship. A government report from January 1946 found seven hundred thousand children in Czechoslovakia living in poverty; half had tuberculosis. Young Karel suffered from severe middle ear infections. At the time they were treated by poking a hole behind the ear to drain fluid. Karel would bear those scars for the rest of his life.

Even though Czechoslovakia was counted as part of the Soviet sphere, and the Communist Party was in the ascendancy, politics remained democratically contestable for at least three years after the war. In the May 1946 elections, the Communists received the most votes, with a 38 percent share. Gottwald, the Communist leader who had fled in 1938, returned to lead an eight-party coalition government as prime minister. Beneš, a Social Democrat, stayed on as president. In the meantime, the Communists were infiltrating institutions from the ground up.

A university student named Rita Klimová, then an ardent Stalinist who—in a classic Cold War about-face—later embraced free market zealotry to become Czechoslovakia’s first post-Communist ambassador to the United States, tried to recruit a young Karel to spy on his classmates. “She told me I could have anything I wanted, party membership when you are fifteen or a diplomatic career, or whatever,” Karel said. “I told her to go fuck herself.”

Karel was already proving himself a willful, to put it kindly, individualist. “I got into trouble right away with some of the other kids. We were protesting the hanging of Stalin’s picture on the wall.” In 1946, that was impolitic, and Karel was briefly expelled from school. “I guess the Communists were still not strong enough, so I succeeded with an appeal,” Karel recalled.

He joined a scouting group, traveling to England in 1946 and France two years later. “Until my fourteenth year, I was raised by my father. I was a boy just like all other boys—perhaps only more mischievous, for I have a very lively temperament,” he would later write of himself in a university admissions essay. “I joined the scouts, and it was good for me, because I came in contact with a group of boys my age and I had to adjust my behavior accordingly.”

The people of Prague also wondered how best to behave in this new status quo. With little idea of what else to do, they naturally reverted to prewar cultural norms. Karel recalled that he “went to church regularly, because my father is a fanatical Catholic.” That practice was to continue “until I was thirteen to fourteen years old. After that, the church’s teachings were too strong even for my adolescent head and I became a heathen, which I remain to this day.”

As well as his metaphysical doubts, Karel had another good reason to stop attending Mass. The church, like many other traditional Czechoslovak institutions, was about to be eclipsed by the Communist Party. On February 26, 1948, the headline in the Communist Party’s Rudé pravo newspaper read, “The People Cleanse the Republic of Saboteurs, Traitors and Unreliable Elements,” as the Communists asserted full control. Non-Communist ministers in the coalition government had resigned over a dispute about policing. They had hoped the tactical move would force a policy shift, cabinet reshuffle, or new elections, but instead the remaining Communist ministers simply continued governing without them.

“The parties of order, as they call themselves, died by the legal state they created,” Jan Kozák, a member of the Communist Party’s central committee, wrote as the soft coup of February 1948 hardened.

Under Soviet guidance Karel’s future employer, the Státní bezpečnost (State Security, or the StB), was created—merging intelligence, counterintelligence, and internal security in a single organization. On March 10, Jan Masaryk, Czechoslovakia’s foreign minister and son of the country’s founder-president, died after a mysterious fall from a ministry window. On May 9, the Communists imposed a new constitution. In the May 30 elections, more than 87 percent of Czech votes and some 85 percent of Slovaks supported Communist-allied candidates. On September 3, 1948, Beneš—the last prewar president, leader of the wartime government in exile, first postwar president, and bridge to the golden age of the First Republic—died.

Confident that friends and fellow travelers now controlled Czechoslovakia, the Soviets asserted themselves elsewhere in the region. In hopes of subsuming British-, American-, and French-occupied West Berlin into what was otherwise Soviet-controlled terrain, on June 24, 1948, the Soviets blockaded the allied zone from the rest of the world. Two days later, the United States launched the Berlin Airlift, flying in thousands of tons of supplies every day. It proved mere overture to the division of Germany into the Western-allied Federal Republic and the Soviet-backed Democratic Republic the next year. All-powerful Germany had splintered in two and hardened into the front line of a new kind of war.

On June 28, Yugoslavia was expelled from Cominform, the Soviet-led body directing the global Communist movement. Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito had liberated his country from the Nazis without Soviet assistance and thus insisted on maintaining independence from Moscow. In response, Stalin cut him off, and henceforth the term Titoist became shorthand for any supposed conspirator or terrorist deserving of death in Eastern Europe.

Spotting an opportunity, the United States countered by supplying Tito’s Yugoslavia with aid, and early moves by both sides upped the ante to codify the early Cold War. In 1947, the CIA was created, and the next year, the US National Security Council expanded the CIA’s modest mandate to include “propaganda, economic warfare; preventative direct action, including sabotage, anti-sabotage, demolition and evacuation measures; subversion against hostile states, including assistance to underground resistance movements, guerrillas and refugee liberation groups, and support of indigenous anti-communist elements in threatened countries of the free world.”

***

The political tumult, a grotesque amalgamation of rigidity and absurdity, was dizzying, especially for a teenage boy. So young Karel Koecher battled away on the home front. In 1949, he started attending the French lycée in Prague, a school full of “girls who were beautiful because their mothers were beautiful,” Karel recalled. As he and eight other newcomers joined up, they were considered “social nobodies.” Still, Karel picked up the new language fast. Out of his element, Karel’s burgeoning disdain for authority surfaced following a round of staffing changes, after which “the teachers’ department started reeking of undisguised philistinism,” he would write.

“I found it revolting to flatter the professors and then later slander them behind their backs, to nod obediently to everything and never say what I think, not even to my classmate. So I was always in a fight with the school rules. That lasted until my graduation,” he continued.

Karel took his rebellious schoolyard persona out into the streets too. In November 1949, he met up with classmate Jiří Kodeš in Prague’s Wenceslas Square. There, they connected with a third student, Michal Tanabauer. “We decided to form this illegal group where we would be doing all sorts of things against the current regime,” fifteen-year-old Karel later admitted under interrogation from the StB.

A week after their first meeting, Karel received a letter setting a second rendezvous for Wednesday night on Prague’s famed Charles Bridge. At six o’clock, Karel joined up with his coconspirators, and the group moved to the shadows of a nearby park to plot. The next week, they met again. A student who identified himself as Josef Urban “stressed that on January 1 it is all going to burst and that we need to prepare ourselves. He further said we are expecting a lot of money,” Karel said later. “He also said he has some weapons hidden in his chimney and that he will lend them to us if we need them. After Christmas we were together in Prokopské údolí [a wooded recreational area in Prague], where Urban showed us an old revolver and an old gun. He fired it twice.”

According to StB files, Urban implored the rest of the group to scan their neighborhoods for gun shops or potential weapons caches. “Prior to Urban leaving for the New Year holidays, he mentioned that he knows a certain person who has some connections to the American embassy. After his return he told us he managed to get the name of this person and his name is Bach,” Karel later told his interrogators.

Early in January, in an attempt to find this mysterious, possibly mythical Bach, Karel, Urban, and others visited the US embassy. They were turned away. “When it comes to the weapons or the guns, he would always talk about seven guns, revolvers, that he was hiding at home,” Karel told the StB.

In a trial run of clandestine meetings to come, Josef Urban asked Karel and Michal Tanabauer to go to the Romanian wine bar on Rybná Street to congregate with another rebel group. The meeting was set for 9:00 p.m. “They were supposed to give us some sort of a letter,” Karel later told the StB. “We were supposed to wait until three young men came to the bar and then we were supposed to ask them for matches. Then they were supposed to give us the answer that they don’t smoke and offer us something to drink. Then they were supposed to give us a letter. We never saw any of those young men; we waited for about an hour.”

Instead, Karel and his friends were arrested and hauled in for questioning. The StB files make it clear that the group had been penetrated by informants from the beginning. Karel was eventually released without charges—even Stalinists, it seems, make exceptions for inane teenagers—but he had already acquired a permanent StB file.

“I have joined this group against the state, which was further supposed to initiate some actions against the state and the democratic systems in the Czechoslovak state. I apologize for my behavior,” Karel confessed to the StB. “I did not actually take the whole thing seriously in any way. I understood it as a romantic adventure. I have not alerted the security apparatus; I have not told them about the existence of such a group and that was because I did not want to let my friends down.”

Karel’s social circle was hardly the only one penetrated by Communist agents. “It was all over by 1950,” he recalled. “They had spies everywhere. It was absolutely impossible to resist, especially in an armed way.”

Cold War paranoia was at an all-time high everywhere. The Korean War kicked off in June, and the view from Eastern Europe was scary. In 1950, the Soviet economy was about 30 percent the size of that of the United States. Americans had 369 operational atomic bombs; the Soviets had 5. The same year, another US National Security Council directive, NSC-68, cleared the way for the American government to use “any measures, overt or covert, violent or nonviolent,” in the name of national security.

The gloves were off, and over the next three years, the number of covert CIA staffers increased from 302 to 2,812, with another 3,142 contractors working abroad. Seven CIA stations became forty-seven, and the budget for covert activities ballooned from $4.7 million to $82 million. On November 1, 1952, the United States tested its first hydrogen bomb. Ten months later the Soviets did the same. In 1953, the CIA overthrew the democratically elected leftist Mohammed Mosaddegh in Iran as the “third world” emerged as a Cold War battlefront.

Under Communist leadership, Karel’s homeland underwent radical change. “The consequences of the communist social revolution had been felt more dramatically in Czechoslovakia than elsewhere, in large part because it really was a developed, bourgeois society—in contrast with every other country subjected to Soviet rule,” historian Tony Judt wrote.

In 1948, 60 percent of Czechoslovakia’s trade had been with the non-Communist world, but five years later, that number had fallen to 21 percent. In 1953, currency reform decimated the savings of everyone with anything left. As Soviet security advisors asserted control over the StB, political purges accelerated. During the 1950s, there were an estimated one hundred thousand political prisoners in a country of thirteen million people. Titoists, Trotskyites, and bourgeois nationalists were the targets. As of spring 1951, the Soviets directed Prague to root out so-called Zionists too, including Rudolf Slánský, the Communist Party’s second-in-command. As if to guard against anyone presuming Slánský innocent following his November 1951 arrest, he was branded with a sterile, yet prejudicial, nickname in the press—“The Spy Slánský.”

A spate of similar arrests followed, and the resulting trials were broadcast on national radio between November 20 and 27, 1952. Eleven of the fourteen accused in the Slánský trial were Jewish. The indictment alone took three hours to read, with the defendants accused of being “Trotskyists-Titoists-Zionists, bourgeois nationalists and enemies of the Czech people,” alleged to be working “in the service of American imperialists and under the leadership of Western intelligence services.”

All fourteen were convicted. Three received life sentences, and the rest were executed, their ashes scattered on an icy road outside Prague. In a preposterous twist, the Communists tried to spin the Slánský episode as emblematic of their love for the Jewish people. “Normally bankers, industrialists, and former kulaks don’t get into our Party,” President Klement Gottwald said. “But if they were of Jewish origin and Zionist orientation, little attention among us was paid to their class origins. This state of affairs arose from our repulsion of anti-Semitism and our respect for the suffering of the Jews.”

Some estimate more than one million Communists were killed in Eastern Bloc purges during the years 1949 to 1953. With comrades like that, who needed enemies? As the violent birth pangs of a new totalitarian age subsided, a certain repressive banality set in. Then, on March 5, 1953, Josef Stalin died. Among his final words, muttered from the depths of a paranoid confusion he had managed to institutionalize, he said, “I’m finished. I don’t even trust myself.”

___________________________________

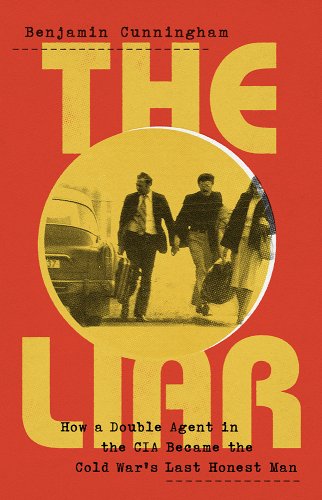

This article has been adapted from The Liar: How a Double Agent in the CIA Became the Cold War’s Last Honest Man by Benjamin Cunningham. Copyright © 2022. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group.