The Cold War was not an event. It was the air you breathed.

I could not remember being without it even if I was about as aware of it as air itself. It was there. It was air, it was smoke—it was the smoke curling up from ashes of Berlin in 1945.

So. . .we breathed this chilly air for a lifetime.

I’m a child of the Age of Austerity, born just after the hot war, which blended almost seamlessly into the cold war. The last relic of the hot war was rationing, which lasted in Britain until 1957 (about as long as it took Russia to release the last German POWs), although most food items had come off by 1952. I still have my ration book. Pinned up above my desk as a ‘memento-I-know-not what.’ It was a potent symbol of the war we had won, lingering into the new era, the news from Berlin and Korea, of the war we could not win.

In 1989 Channel 4 TV (UK) sent me to Berlin to cover the opening of the film of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (yes, there have been two versions) at the Berlin Festival. It was scripted by Harold Pinter. We went via Prague. Harold introduced me to Vaclav Havel—quite possibly the human embodiment of the changing times. Harold flew on to Berlin, I chose the train. It was weeks before I saw him again, as once I’d seen what was happening at the Wall I diverted the crew to filming there. I never got to the Festival. Instead I breathed the smoke of cordite from fireworks, atop the Berlin Wall standing with hundreds of others. Looking down on rather narked DDR guards to whom we were just a pain-in-the-ass.

Some, most, breathed in freedom. Understandable. All the same I could not and have not been able to tell myself it’s over. If you don’t believe me, breathe deep, the chill is still there. Putin v. Trump may not be as cold Khrushchev v. Kennedy but you don’t have to look hard to see the frosting on the cake. Along the way the Cold War might have given rise to the most captivating genre in both film and fiction. I think I’ll call it Cold War Noir, at least until I come up with something better. It’s the culture of my lifetime.

If it is a genre unto itself. . .then it comes out of le Carré’s work as surely as the Russian novel crept out from under Gogol’s Greatcoat. He set the benchmark, the tone, the maxim. . .‘How to combat evil without becoming evil’. . .it’s genre of love, loss and betrayal. It might be summed up with ‘who can you trust?’ This is our theme. . .whether it’s played out as tragedy or comedy.

Rough-mapping the genre, it’s tempting to begin with Graham Greene’s The Third Man (a book as well as a film, although the film came first) but apart from the pure magic of its setting, post-war Vienna under occupation by the four victorious powers, the city that would become the world capital of espionage for the next ten years, it really doesn’t have a Cold War theme. Instead let’s say it begins with a slightly later Greene that just pre-dates the first le Carré.

Graham Greene, Our Man in Havana (1958)

The tale of Wormold, a man strapped for cash who reluctantly agrees to spy for the British in Cuba, where he runs an electrical goods shop. Greene called many of his books ‘entertainments’—that doesn’t mean they do not end in darkness. Wormold invents a spy network, and passes off drawings of vacuum cleaner motors as plans for weapons bases. I rather think le Carré has read this. His The Tailor of Panama reads like an homage to Greene. The film? Alec Guinness at his best.

Ian Fleming, From Russia With Love (1957)

Occasionally, perhaps often, a Bond film improves on a Bond book. More often they just ignore everything but the title. The film of Goldfinger, for example, neatly circumvents the impossibility of making off with the loot from Fort Knox by introducing an atom bomb—“I prefer to think of it as a device.” From Russia with Love is probably one of the least changed in the transition to film. Swap SMERSH for SPECTRE, but the Orient Express and the thoroughly captivating, thoroughly wicked Rosa Kleb remain as stars.

Richard Condon, The Manchurian Candidate (1959)

Is Richard Condon’s best known novel even in print now? So much of his work isn’t. I got lucky and stumbled across An Infinity of Mirrors, being used as ‘period decoration,’ in a pub in Soho. It’s the only copy I’ve ever seen. So I nicked it. Books are not wallpaper. The Manchurian Candidate is prescient, twice over. A political assassination some four years before Oswald shouldered his rifle. But ask yourself, isn’t the Manchurian candidate in the White House right now? I wonder who’s holding the Queen of Diamonds.

The Frankenheimer film is first rate. Don’t bother with the remake.

John le Carré, Call for the Dead (1961)

You may very well think it perverse of me not to pick The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, but this is the book that introduces Smiley. As such, it has to be a landmark in Cold War Noir. It was filmed a couple of years later with James Mason as Smiley, renamed Dobbs. I don’t think John le Carré cares much for the film, but it, like the book, has a stark simplicity, showing a cold war growing inevitably out of blurred margins of the hot one. It’s one of my favourite films.

John le Carré, The Looking-Glass War (1965)

This too has elements of Greeneland. A cockamamey scheme that cannot possibly work. The Cold War, or at least the British end of it, exposed as amateurish. In the end you feel the only truth is ‘trust no one.’ It was filmed in 1969, during the brief stardom of Christopher Jones. Perhaps most notable for an early appearance by Ray McAnally, who played ‘Rick/Dad’ in Arthur Hopcraft’s brilliant adaptation of le Carré’s A Perfect Spy in 1987. Anyone seeking an insight into that character can do no better than read le Carré’s essay The Author’s Father’s Son.

Len Deighton, The IPCRESS File (1962) and Funeral in Berlin (1964)

Two choices by Len Deighton — the book The Ipcress File is complex and difficult. Almost an experimental novel. The word ‘file’ means just that. Funeral in Berlin is a far easier read. (Between the two comes Horse Under Water (1963) which I suspect is regarded as a Deighton oddity.) But. . .The Ipcress File became one of the most iconic (not a word I care for) films of the 60s, with Harry Palmer (Michael Caine) seen as a less flash alternative to James Bond. . .he cooks, he listens to music. . .dammit he made a whole generation of us nerds look cool by wearing glasses. Superb direction by Sidney J. Furie. I’ve no idea whether Sid ever made another film.

Ian McEwan, The Innocent (1990)

I wish I’d written this. I knew the story on which it’s based. . .another tunnel under Berlin, an expensive act of espionage utterly blown by the British double agent George Blake, but. . .but the finest novelist of my generation got there first. I think it may be the only McEwan novel dealing directly with the Cold War. It’s been filmed, he wrote the script himself, but I’ve never seen it.

Joseph Kanon, Leaving Berlin (2014)

Anything by Joseph Kanon. I think I’ll settle for the last one I read, Leaving Berlin. Berlin before the wall. The setting may be the most familiar one in Cold War fiction, but the theme isn’t. It isn’t about ‘us,’ the victors, it’s about ‘them,’ the Germans. About the poverty of Berlin in the 40s, about survival, about the exploitation of a writer as an agent of the CIA. I found this fascinating and original—even Brecht appears as a minor character, portrayed by JK without reverence. Berlin stands for the rest of us, for all of us at the depth of the frost. . .caught between the two great and ruthless powers.

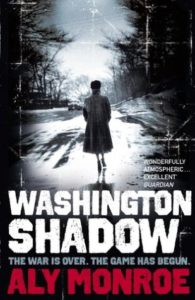

Aly Monroe, Washington Shadow (2009)

I took too long to discover Aly Monroe. Too long in that we enrolled in the same English university on the same day fifty years ago and did not meet face to face until 2012. . .by which time Aly had three books in her Peter Cotton series in print. Washington Shadow is the second. I’ll let Aly speak for herself :

“Cotton is a kind of half—son of Empire, something of an outsider in the UK and anywhere else he goes. His gaze on the US is not that of a Brit—and his gaze on the British is not that of a native.

“Washington Shadow is set in 1945, the year John Maynard Keynes was sent to Washington to beg for a loan from the Americans. I wanted to show the impoverished British experiencing the fabulous wealth of the US, at the time, and the transformation of Washington DC from provincial capital to the centre of the new world order.”

This novel captures the beginning of the unhealing rift between British and American Intelligence that was confirmed by the espionage of Klaus Fuchs and defection of Guy Burgess, and writ in stone by the fiasco that was Suez. Our empire was over. We had no role on the world stage. It just took ten years for us to know it. Listening to British politicians today it is possible to think that there are those among us who still do not know.

Why Aly Monroe is not published in the USA baffles me. And there’s a hint the size of a small planet.