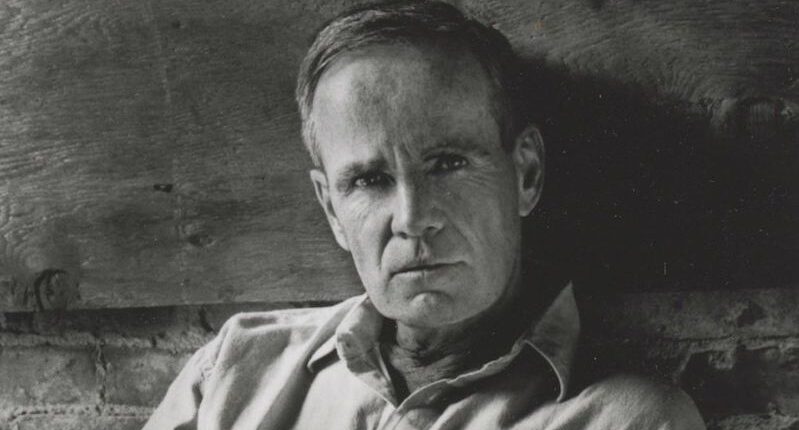

The late Cormac McCarthy, widely regarded as the literary heir to Herman Melville and William Faulkner, a traditionalist in a sea of deconstructionists, had a flair for violence.

Sometimes he boiled everything down to the brutal essentials. From his novel “No Country for Old Men”:

“Chigurh stepped into the doorway and shot him in the throat with a load of number ten shot. The size collectors use to take bird specimens. The man fell back through his swivel-chair knocking it over and went to the floor and lay there twitching and gurgling. Chigurh picked up the smoking shotgun shell from the carpet and put it in his pocket and walked into the room with the pale smoke still drifting from the canister fitted to the end of the sawed-off barrel.”

And sometimes he went more baroque. From one of the more famous sequences in “Blood Meridian,” in which a tribe of Native Americans butcher a legion of hapless soldiers of fortune:

“A legion of horribles, hundreds in number, half naked or clad in costumes attic or biblical or wardrobed out of a fevered dream with the skins of animals and silk finery and pieces of uniform still tracked with the blood of prior owners, coats of slain dragoons, frogged and braided cavalry jackets, one in a stovepipe hat and one with an umbrella and one in white stockings and a bloodstained weddingveil…”

Whatever the action, he gave it weight and texture. McCarthy’s style, light on punctuation but heavy on the conjunctions, sprinkled with the occasional sentence fragment and anachronistic word, is simultaneously reminiscent of a Biblical text and an old-school noir novel; think Deuteronomy meets Jim Thompson. His early books were steeped in Southern Gothic; as he progressed through the decades, he shifted West for his masterworks (“Blood Meridian” and the Border Trilogy), his prose increasingly lean. His last two books, “The Passenger” and “Stella Maris,” coalesced these literary forms; the former is dense and heartfelt, occasionally galactic in scope, while the latter is a pure dialogue of ideas that ends on a nihilistic note.

Attempting to analyze McCarthy’s work through the lens of ‘crime fiction’ is an interesting exercise. His books were saturated with ‘crime’ in the most primal sense: murder, theft, baby-eating, massacre and genocide. “There’s no such thing as life without bloodshed,” McCarthy told The New York Times in 1992. “I think the notion that the species can be improved in some way, that everyone could live in harmony, is a really dangerous idea. Those who are afflicted with this notion are the first ones to give up their souls, their freedom. Your desire that it be that way will enslave you and make your life vacuous.”

Crime fiction also revolves on the axis of crime and punishment, law and outlaw—but even in his most grounded novels, McCarthy wasn’t interested in the niceties of societal justice. The marauders of “Blood Meridian” pillage with impunity until more savage forces tear them apart; the police in “Child of God” are little more than a cleanup crew once the full scope of the protagonist’s horror is revealed; the cops who scurry through “No Country for Old Men” are powerless before the ruthlessness of Anton Chigurh, a professional hitman and fixer who pontificates about fate before murdering people; and in “The Road,” set in a post-apocalyptic America coated with ash, the laws and tenets of the old world are a fading dream.

Much of crime fiction is obsessed with balance: the forces of law and order win, or at least the guilty get what’s coming to them. The arc of McCarthy’s literary universe bends not toward justice but something far darker. In “Blood Meridian,” man is described as the “ultimate practitioner” of war, the “ultimate trade.” War, in the book’s context, isn’t the orderly movement of troops around a field—it’s slaughter and pillage, much of it conducted on territory where burning down a village and killing its inhabitants for their scalps is considered just another Tuesday. Humanity perfected violence, and violence pushed humanity onto a merciless evolutionary path: Sheriff Bell, the old-fashioned lawman in “No Country for Old Men,” laments that a man he sent the death row “wasn’t nothin compared to what was comin down the pike.”

That incomparable force is Anton Chigurh, not so much a psychopath as a human tailored to his environment. Among McCarthy’s rogues, he’s matched by the Judge, the giant killer genius at the heart of “Blood Meridian,” and Malkina, the antagonist (or perhaps the protagonist?) of “The Counselor,” a 2013 film written by McCarthy and directed by Ridley Scott. They’re all apex predators; the only laws that matter to them are the most primal ones.

With “The Passenger,” the longer of his final two-book salvo, McCarthy starts out with the trappings of a conspiracy thriller. A plane has crashed into the Gulf of Mexico, and a passenger onboard is missing, along with an instrument panel and the pilot’s flight-bag; one of the divers sent to survey the wreck, Bobby Western, soon finds himself pursued by mysterious government men. It seems like McCarthy’s setting up a tense chase along the lines of “No Country for Old Men,” but then the narrative… trails off.

Instead of pursuits and gunfights, we’re treated to long, digressive conversations about everything from nuclear physics to the JFK assassination. In the months since the book’s release, theories about this narrative drift have proliferated across the internet. Perhaps the story is actually Bobby Western’s coma dream (it certainly plays like a dream at moments); perhaps McCarthy performed the ultimate flex of the world-famous writer: using a narrative as a thin pretense to talk about the things that interest him. Whatever the motive, crime fiction aficionados heading into “The Passenger” expecting a thriller were treated to something radically different.

“The Passenger” (and to a smaller extent, “Stella Maris”) also offers a counterbalance to the darkness and nihilism that dominated so many of McCarthy’s previous narratives. It’s a cruel and violent world, the books suggest, but love among family, among friends, is what sustains us through it: “He knew that on the day of his death he would see her face and he could hope to carry that beauty into the darkness with him, the last pagan on earth, singing softly upon his pallet in an unknown tongue.” It’s our solace among the bloodshed.