Twenty-one years ago. That’s when Craig Clevenger’s debut novel, The Contortionist’s Handbook, came out. That’s when I read it. The book, about a young forger constantly reinventing himself to avoid the authorities—which, if you’re into labels, you could call neo-noir—was like a bolt of lightning in my hands. Stark and gritty, thoughtful and ever so carefully-crafted. If I had to make a little pile of books that pushed me to knuckle down and make a career as a writer, Handbook would hold a place of esteem near the top.

A short time after I read it, I wrote Clevenger—just tracked down his e-mail somewhere—and asked him if he had any advice for an up-and-comer. He came back with a 10-point list that, even looking at it now, so clearly formed the framework of who I am today as an artist. I was lucky to take a couple of workshops with Clevenger along the way, and his thumbprints are all over my work.

One of the points he made feels appropriate now:

Know that you might fail. Years of effort might yield nothing, not even a single publication in a small magazine. Sometimes dreams don’t come true, in spite of what Hollywood would have us believe. If you know that, and believe it to be true, and still want to write because the risk means nothing next to the need to do it, then even the most minor successes will be absolutely intoxicating because they will be wholly and completely yours.

Appropriate, because Clevenger followed up Handbook with Dermaphoria, a fever-dream drug-trip about a clandestine chemist that was bigger, weirder, and went deeper. It held the promise of a visionary writer who was just getting started.

That came out in 2005.

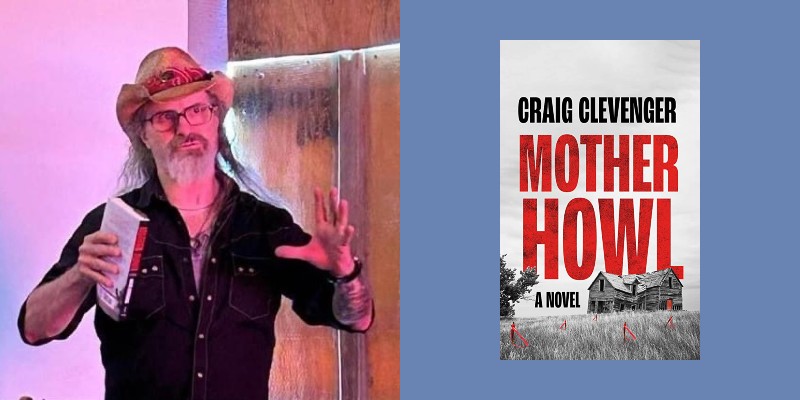

And here we are, with his follow-up: Mother Howl.

So, yeah, it’s been a minute. But the wait was worth it. The new book, published by the new crime imprint Datura, follows Lyle Edison, on the run—again, with reinventions—after his father is revealed to be a prolific serial killer. And then he crosses paths with a mysterious stranger, Icarus, who has a message for him… and may or may not be some kind of divine being.

The blurb I gave it was:

“Mother Howl is a live wire plugged into a world only Clevenger can see, and once he shares that vision with you, you’ll be powerless to look away. Equal parts vicious and elegant, deeply thoughtful and even more deeply human—the highest compliment I can pay it is: it reminds me of the power a book can have and challenges me to step up my own game.”

The blurb I wanted to give it?

“Clevenger, that m*****f*****, ought to have stayed retired—how in the sweet world of f*** are any of us supposed to compete with this?”

Rob Hart: So I guess the first question is, where have you been?

Craig Clevenger: How do I answer that politely and diplomatically? After Dermaphoria, I started writing this book while my old publisher was still in existence. But they eventually went under. In going under, they were determined to go under with a fight, and most of the writers in their stable became cannon fodder in that fight.

So for one thing, it began a years-long stretch of couch hopping, because a lot of my livelihood was coming from that. It’s hard to maintain a stable, steady writing habit when suddenly I’m couch hopping.

Beyond that, my first novel took two years, my second novel took three and a half, four, and I was savvy to the pattern early on. I want to be a better writer with each book. And this one I could tell was going to go on longer. The idea wouldn’t leave me alone. I think smarter writers, better writers would’ve just ditched something that wasn’t cooperating a lot sooner. This one, at least twice, maybe three times, I just tried to abandon it and said, “No, this is not working. Reboot, do something else.”

And so I had to have a lot of dead ends and false starts, and a lot of things just went into the files that never got used, until it finally took shape. That’s sort of the broad brushstrokes of everything because yeah, it’s been a very long time. And then on top of that, once it was finished, finding an agent and then that agent finding a publisher.

I’ve certainly had those myself, with ideas that aren’t leaving me. Then I feel like I’m hitting a wall I just can’t get past, and end up putting it aside because I hope at some point, I’ll come back to it. What was it specifically about this that felt like, “No, this is the project and I’m going to beat it into submission”?

I wish I had a specific part of this book I could point to, but you know how when you step away from the work and you’re doing whatever—at the gym or on the bus—and scenes start playing in your head? That’s just what kept happening. It kept coming back. Also, I’ve said many times before that I’ve never thought of writing in terms of a career. I don’t think in terms of future projects or my resume or a portfolio or anything. I approach every story like it’s the last thing I’m going to write and I’m on my deathbed.

So I don’t have a lot of irons in the fire. My notebook’s always filling up with brainstorms and what-ifs and notes to myself, but I don’t have multiple things in progress. I don’t shift gears to something else. I’m pretty obsessive about something when I start. So as far as this one, it just seemed important to me on some level that I’ve never been able to really figure out. I don’t know if that makes any sense at all.

No, it totally does. And I thought it was really interesting, that it felt like a departure for you. Because the first book—straightforward crime novel about a forger. You’ve got the second book, Dermaphoria, which got into some weirder places, around this idea of drug use and tripping. I’m always kind of hesitant to assign things genres, but this is almost like an urban fantasy-ish, crime fantasy sort of thing. What attracted you to broadening your spectrum there?

I refer to it as crime adjacent rather than crime. Crime adjacent with a touch of magical realism. The writers that have left the greatest impression on me have always been the ones that are the hardest to pin down, who are very genre fluid. I think Rob Roberge told me, I’d have to check the source, I think it was Steve Wynn, the musician, who said, “Every record company has someone in their marketing department whose job it is to take my work and condense it into a fifty-word description for a catalog. That’s their job. My job is to make their job as difficult as possible.”

The writers who have always left the biggest impressions on me are the ones that are fluid, that are not afraid to ignore the lines. And my imagination has always gone that direction. Most of what I read as a kid was science fiction and fantasy. But when it came to writing, I could never bring that stuff in. I always seemed to gravitate back towards the here and now. This time, I felt more comfortable going that direction. It seemed like that would be the best way to tell the story.

It’s also more fun, right? Because what’s the point of just coloring inside the lines? When you’re writing a book, you can do literally anything that you want.

When I was younger, like I said, I read science fiction and fantasy and I read it to escape. I discovered crime fiction, noir fiction in particular, James Cain, Jim Thompson, in my 20s. And I realized that’s what I read to understand what I was escaping from, and that’s a whole other bit of backstory there. I’ve always gravitated toward that stuff. But yeah, I’ve wanted to play around with form a lot since then.

I wanted to be a science fiction writer when I was younger because I didn’t understand the point of it, if I have my entire imagination of at my disposal, why do I want to write a story about coming of age in the Midwest? Why keep it grounded when I have all these other options? Growing up, I understood that. There’s a good reason for that. But now that stuff is bleeding back in, and it just seemed like the only way to tell the story.

You’ve got to use the tools that feel right for the job. And that’s the struggle sometimes—finding the right tools because, especially in a story like this, it’s very sprawling and it’s a little bit more complicated, because you have these two shifting narratives. I was reading it on my iPad, the copy that you sent me, and when you finally get where the two stories converge, it’s not until the fifty percent mark of the book, which I loved. The way they both felt so scattered and all of a sudden just clicked, they came together.

I tried really hard to have every scene where there’s a transition between the narrative, where it ends with one of them going to sleep and the other person waking up. I tried really hard just to underscore thematically that idea. But with having years of editing and reshuffling and working up chronological things that didn’t actually work for at least half of it.

So as much as I can, there’s the transitions between Lyle and Icarus, one is going to sleep and the other is waking up. That didn’t pan out to be 100 percent in the final draft, but that’s what I tried to do. It’s also the first book I’ve ever written almost completely in chronology, start to finish. It shifted around with the rewrites, but I pretty much started at the beginning of the narrative and wrote in order to the end, with the exception of the chapter with Lyle’s father.

So does that mean your previous books, you’ve kind of written them out of sequence or out of order?

Yeah, just trying to figure out where the load-bearing plot points were, and what I felt like I knew I’d worked out enough to get on paper, and then try to bridge plot points between them. This one I just started at A and wrote to Z.

That’s fascinating to me because—you’re doing an event with Jordan Harper. And Harper is a phenomenal writer and I love his stuff, and he writes out of order. And my brain just doesn’t work like that. I can’t conceive of it. I always write A to Z. The idea of pulling things out and doing them separately just seems kind of nuts to me. But I’m always fascinated to hear that someone could produce a really good book using a completely different process, because it just does not compute.

Sara Gran and I talked at length about that. And the more writers I talk to, the more radical variation I see in process. Like James Ellroy, you probably know, outlines to the Nth degree. His outlines will often run half the length of his books or more, they’re so detailed. Steve Erickson doesn’t outline at all. I don’t think Sara Gran outlines either. Helen Phillips outlines visually. She doesn’t do index cards or Roman numerals, she has a collage sort of thing. She just collects things that spark her mind and fit to the story, and builds these displays almost. So my process changes with each book. And the thing that has stayed consistent though with each of them is I take great pride in being able to write a good closing line.

A some point in the process, once I understand at least thematically the crux of the book—the closing line, the curtain line, the very last line of that story will crystallize in my head. And I will keep that either taped above my desk or on the very last page of my notebook because I’m working longhand. And when I fill that notebook up and I have to crack open a new one, one of the first things I do is go to the last page and write that closing line there. And that’s my guidepost that I’m always writing towards. That’s the one thing that stayed consistent.

That’s interesting. It’s a process and our process changes with each one, but there are those things that we need to stay consistent so we can stay grounded. But it’s also kind of fun to learn and grow a little bit with each one and push yourself and see what you can get out of it.

I want to be a different writer with each book, and a better writer as well. Ideally, I would like someone to read the Handbook and read this one without the byline, and not know they were written by the same guy. And I’d like to say the same thing of the next one as well.

So way, way, way back in the day, I remember when The Contortionist’s Handbook came out, it caused a stir in the crime fiction community. Even now, I’ll mention it to people and they remember that book. And it’s been a little bit of time since. How does it feel to be coming back out of the deep freeze? Are you hoping those people are still going to be there? Are you getting positive reactions from people?

I hope they’re still there. [The Handbook] is out of print in the US right now. I hope the people that first read it are still there, and maybe there are some new readers as well. It’s hard to gauge. People keep asking about the book, “Are you excited? Are you excited?” And I’m not. I’m relieved. My first book was exciting. This book, I feel like I’ve been stranded in the middle of nowhere for 15, 18 years, and I can finally see a tow truck in the distance. It’s a feeling of relief, like I’m back from the dead.

As far as who’s out there, it’s weird because unless you’re Stephen Graham Jones or Stephen King or somebody huge, you’re online following doesn’t seem to match your sales. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of overlap. I’m happy to see the responses I’m getting on social media, but I’m hoping that’s not the whole story. I know that’s the case for you, given your sales and the exposure you’ve had and such, you have way more followers than I do, but I still don’t think those followers equate to your readership. Am I making any sense?

Absolutely. An agent told me this years ago, which is 100 percent true: 10,000 followers is not 10,000 sales. I see the value in social media in terms of keeping people updated on releases or events or just saying dumb stuff every now and again. I don’t think social media actually sells a lot of books. Unfortunately, it’s hard to point to something else and say, “Here’s the thing that sells books.” If a movie gets made out of your book starring Brad Pitt, that’s going to sell books. Everything else is kind of a crapshoot.

I think doing all these things, whether it’s a bookstore appearance or an interview or a podcast or an Instagram account, the crapshoot isn’t to have a one-to-one book sale. It’s more that, the more people you reach, the better chance you have of hitting that one person who’s going to be some sort of amplifier.

Chuck Palahniuk blurbed my first book because a reader sent it to him, unbeknownst to me. Someone read a review, got it, read it and said, “I think he might like this.” Didn’t know him personally, just emailed it or mailed a hard copy to a webmaster unsolicited. That was Wendy Dale, who I owe a great deal of thanks to. So I’m not looking so much for a bunch of people to sell to, as much as there’s one person out there that maybe will carry some weight. You notice how I’m really working hard not to use the word influencer?

It’s admirable. But I think you’re exactly right. My attitude has always been that it’s a game of inches. I drove to Annapolis last weekend and did a book festival and I sold three books, and you know what? Three books I wouldn’t have sold otherwise, so it’s fine.

And who knows? Maybe somebody there already had the book or knows you or whatever, or saw you and told someone, “Hey, have you read this guy’s yet?” And I don’t want to sound like a mercenary here, that sounds awfully bloodless, just looking for sales. Nobody does this to get rich, but we don’t want to do it for nothing either.

Exactly. So Datura is pretty new. What’s your experience been with them thus far?

I don’t have a lot to compare to, but so far they are night and day. Datura is a small imprint from a larger British media company. They’ve had an imprint called Angry Robot, which is all science fiction. And the same editorial crew at Angry Robot is basically Datura.

My experience has been great. What attracted to me first was they liked the book and wanted to publish it. That goes a long way for a writer. But more than that, looking through their editorial staff and the catalog just for Angry Robot, they really walk the walk when it comes to diversity, and daring stories, and looking for stuff that’s different and original.

You and I have heard this over and over again from submission calls and from agency profiles and magazines and publishers. “We’re looking for dangerous, original, bold voices. We’re looking for daring, original, different stories.” You know all the buzzwords, right? And then the rejections come back and it’s over and over: “We don’t know how to market this. There’s no titles to compare it to.”

Angry Robot really walked the walk, that was my experience with them. And so far, it’s been great. The only downsides is that they’re in the UK and I’m on the West Coast of the US, so everything is a day behind. I get an email from my editor, and unless I email him back at 7 in the morning, he’s not going to get it.

We’ve had a couple of Zoom calls, but largely everything is a day behind, and when you’re coming at a deep freeze, it creates some tension. But they’ve been great. And like I said, they walk the walk. And the other titles they’re putting out on Datura are the same thing.

The thing that I appreciated about Mother Howl so much is I’ve never read anything like it. There are elements to it that feel familiar, but the way that you kind of mix and mash them together, you did that thing that you always do, which I’m always really goddamn jealous of—you write these really intricate narratives and these really dark, dark stories that by the end just have this emotional wallop, that just knock you out. I was hooked throughout the whole book, but those last 20 pages I was like, “Jesus Christ, this is amazing.”

Thanks. Yeah, I get the word dark thrown at me a lot and I get it, and I’ll push back sometimes on that. But this is the first book I’ve written that I think honestly has an upbeat, happy ending in a twisted sort of… not even in a twisted sort of way. Far more than the other two, this is a more uplifting, positive book, I hope. Maybe my threshold for what’s upbeat and dark are very off than most other people’s.

I would absolutely say there was a hopeful element to the end. And I think I felt that viscerally reading it. “Oh, this is going to go real bad for everyone. No one’s going to end up happy here.” And then getting to the end and feeling this sense of relief and being like, “Oh, thank God, that’s actually kind of nice.”

That’s what I wanted. It’s funny because like I said, I wrote all of this in story sequence, not necessarily chronological sequence, but in story sequence. A to Z from the beginning, except for the chapter with his father. That was the one that the deeper I got into the story, the more I realized that that’s the antagonist, at least as he exists in Lyle’s mind.

And I wanted to write that chapter in advance because I wanted to really get my own brain around what was looming over Lyle. And that’s the one chapter I jumped ahead to write. And it took me a while, but when I was done, I was really bummed out. It really depressed me being virtually in the room with that guy for that long. And I had to take a breather after that for a bit because it was just such a bleak, depressing… he was just a horrible human.

I always feel like that’s when you really know something’s working, is when you have that visceral emotional reaction to it.

I’ve heard writers say, especially crime writers, that, “If you’re not surprised, then your reader’s not going to be surprised.” And I think you can apply that across the gamut of emotions or reactions. If you’re moved, hopefully your reader’s going to be moved. But with that character, it was nerve-wracking because there’s a legacy in crime fiction and film, TV and movie drama. The good guy and the bad guy facing off in the room, Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter. And it’s been done so many times before, for good reason, it will be done again. I just did not want to try to contribute anything to that because it’s been done. I wanted to sidestep all of that: “We meet at last, Mr. Bond.”

I didn’t want to have any of that feeling to it at all. And it was important to not give Lyle any sense of artificial closure. I didn’t even want to give Lyle the satisfaction of a denial from his father. He never denies anything because even denying something acknowledges the accusation. Instead, it was all deflecting and dodging and counter-blaming and everything else. The kind of very adolescent defense mechanisms.

And I noticed this when I was reading or watching interviews with killers, unrepentant killers, and I don’t recommend doing this at all, it’s really a drag. But I think the way we put these people on a very dark and creepy pedestal as being these malevolent agents of the devil or something. When you really listen to the way they think, it’s not any different than a child. “It was broken when I got here.” “Well, he started it.” Their defense mechanisms are not very different. And when you take those same childish defense tactics and apply it to multiple human lives, it’ll ruin your day.

You mentioned Hannibal Lecter, great example. Sure, he’s charming and he’s smart, he’s a snappy dresser, but he also eats people. That’s not okay.

I really wanted to make him unlikeable without any of that mystique. That’s one of my frustrations with the way that we cover this stuff is: everybody’s got to have the fancy nickname. Right away, all you’re doing is stoking the coals. When you call someone the such-and-such strangler or slasher or killer or whatever, when you give him the fancy name, already, you’re deifying them in a strange way.

And yeah, that was the turning point for Lyle when he realizes and his father never got that. For a guy who has such contempt for the world, you sure need everyone’s approval a lot, don’t you? I wanted that revelation to kick in.

We’ve talked about Lyle and his dad. I do want to talk a little bit about Icarus too, because Icarus is such a fun, weird character. Especially his manner of speaking. What kind of heavy lifting went into developing that character and finding his cadence?

Honestly, not very much. You said something earlier about sometimes we just want to have some fun with this, you would want to rip the reins off our imagination. And the idea of Icarus… Okay, so my thought was, if he believes himself to be incarnate, just very suddenly, boom, you’re flesh and blood now, language would’ve been just downloaded into his brain, which means he’s just going to cherry-pick his meaning as he finds it. I just wanted to just rip the reins off and having some fun. That’s all it really was, and it came pretty naturally.

Sometimes I would try to come up with a clever way of describing or phrasing something, but for the most part it’s some fairly straightforward grammar swapping. Suffixes or prefixes swapped out for another one that meets the same thing. So qualificated instead of qualified. Once that clicked, it came fairly easily. In fact, it started to ramp up as I wrote to the point where I had to backtrack to early chapters of the novel to make sure his manner of speech was consistent. I just wanted to have fun, because I was really working so hard on the prose with the rest of the book, again, to be a different writer and be a better writer. Icarus was my vacation. He was my comic relief.

Did your copy editor enjoy it as much as you did?

With my French translator, I said, “Are you going to be okay with the Icarus stuff?” And he goes, “No, it’s going to suck.” And I think the copy editor came up with a style guide for his mannerisms, his way of speaking, barring the occasional turn of phrase. She came up with a style guide that summarized everything. So I don’t think she liked it very much, but she did a brilliant job of going after it.

I’ve had some weird conversations with translators, stuff that’s a little too American and trying to translate it into a different language. I feel like once you get into that, you’re really getting into the weeds.

I got to meet my French translator in person when I was over in Paris a while back, and he really threw the light on some things. He pointed out that you can’t translate an accent, which never really crossed my mind. It’s not so much the accent doesn’t translate, but all the things the accent implies or the flavor it gives a story. There is no French, German, whatever equivalent of a Boston, deep South, or SoCal accent. And whatever that brings to the story, they can’t do in that language, so that creates a whole level of challenges. I have a whole new reverence for translators in that respect.

I had an interesting conversation with my French publisher once where she said that she’s read books in English that were fantastic. They moved fast, they were thrilling, they were fun. And then she would read the French translation, and all the magic would be gone. So her biggest challenge was always finding the right translator for the right project.

You know that Brian Evenson is a French translator?

I did not know that.

He translates books from French into English, among his other accomplishments. It’s kind of daunting. If you get your hands on a book, it’s a tiny novella called Electric Flesh. The author’s name is Claro, it’s one word. He’s well-known, a heavyweight French writer. Brian translated Electric Flesh into English, and it is the most acrobatic brilliant prose you’ll ever read. And I can’t imagine what it looked like in the original French and the kind of heavy lifting Brian had to do to make that make sense in English, but it’s just a fantastic read if you have to get your hands on it.

I will look for that. So again, it’s been a while since your last book and now Mother Howl is coming out. Are you working on something next or are you kind of taking a breath or…

I’m been working on something for quite a while, and I’m hoping to lock it down soon. I keep saying that though. It’s hard, like I said, coming out of deep freeze. I told you a while back that honestly, in the midst of that deep freeze, I just gave up. There was a long stretch there, where I told people… “Yeah, I’m still working. I’m still working.” When in fact, I just couldn’t even look at a notebook or my machine or anything. Between my old publisher collapsing and Mother Howl not finding a home and everything else, I just thought, “Okay, I guess maybe my career has run its course. It’s time to rethink all this.”

So I am very slowly getting my rhythm back. And this idea, like everything else, just will not leave me alone, so I guess I’m stuck with it any way. I’ve got it worked out. I’ve got it outlined, and so I’m working my way through the outline. I mean, it’s basically complete. The outline is complete for a complete story. There’s nothing I have yet to figure out. There’s something missing that I can’t quite identify yet, so I’m not rushing through it.

But I am working on something and I know my agent has been patiently waiting. I’ve got more life behind me than in front of me, so I don’t want there to be done 15, 18-year gap before I’m in print again.

So then the final and the most important question is: your main character from The Contortionist’s Handbook made a cameo in Dermaphoria, and then makes a cameo in Mother Howl. Is he going to be in the next one?

I haven’t even thought about that. And I can neither confirm nor deny he makes cameos in the other books. Now that you mention it, I should probably work that in just to keep the joke alive. And I need a cat. There’s always a cat in my stories that is based on real life too.