Running a red light. A ride-along with a friendly neighborhood cop. Binge-watching Law & Order. For many crime novelists, this is as close as it gets to write what you know. But for a small cadre of authors, their experience came from the inside of a prison. What they knew was shouldering the burden of a terrible crime, the public stigma of being labeled a crook, and sometimes a life spent on the run from the law.

A few allowed themselves to be dominated by their identity as criminals; writing turned out to be just a brief sidebar to their time as inmates. Others used what they saw and felt and did in prison to enrich their writing, becoming best-selling and award-winning novelists. No matter what their eventual fate, however, the fiction of these writers—sharpened by real-life crimes—has a hard edge that’s difficult to ignore.

Chester Himes (1909 – 1984)

Born into a black, middle-class St. Louis family, Chester Himes grew up emotionally scarred after his brother, blinded in a tragic school accident, was refused treatment by the white doctors at a local hospital. As a young man, Himes attended college at Ohio State University but had a rebellious, reckless streak that didn’t mesh well with higher education. As novelist and Himes biographer James Sallis put it, “he stood…at a hard right angle to the world.” It wasn’t long before pranks and petty crimes led to his expulsion. In 1928, he was caught attempting to rob a bank and subsequently sentenced to 20 to 25 years in prison.

Behind bars, Himes wrote short stories and novels to pass the time and, with pieces published in Esquire and The Bronzeman (some under the byline of his prison number, 59623), he also earned the respect of guards and other inmates. Eight years into his sentence, he was released and went on to write crime fiction about the black experience in America, such as the searing If He Hollers Let Him Go, as well the hard-boiled Harlem Detective series featuring Coffin Ed Johnson and Gravedigger Jones (more about Coffin and Gravedigger in Malcolm MacKay’s “Crime Fiction’s Unforgettable Outsiders”). Four of Himes’s books, including Cotton Comes to Harlem, have now been made into feature films. Restless and unhappy with the racism he continued to experience in America, Himes moved to France in the mid-1950s and to Spain in 1969, where he died in 1984.

Joan Henry (1914 – 2000)

British debutante Joan Henry had an unlikely start as a criminal. Born into a wealthy and influential family that claimed an Earl, two Prime Ministers, and Bertrand Russell among its members, Henry was a writer of romance novels before gambling debts caught up with her. When she attempted to pass a fraudulent check, she was arrested and sentenced to a year in prison in 1951. Upon her release, she wrote the autobiographical best-seller Who Lie in Gaol, an exposé of the harsh treatment and neglect she’d observed in Holloway Prison. The book became the inspiration for the 1954 film The Weak and the Wicked.

The director of that movie, J. Lee Thompson (of The Guns of Navarone fame), gave Henry the idea for her next project, the novel Yield to the Night, the story of a young woman sentenced to death for murder. Thompson, looking to make the book into a feature film like its predecessor, initially had no luck pitching the story to studios due to its progressive stance against capital punishment. But when the real-life case of Ruth Ellis—a nightclub hostess who killed her cheating lover who was coincidentally the last woman to be hanged in Britain—splashed across the British tabloids in 1955, the film was green-lighted and went on to become a success thanks to uncanny similarities to Henry’s novel. She went on to write several plays for screen and stage, many of them dealing with social issues.

Malcolm Braly (1925 – 1980)

By Malcolm Braly’s own admission in his 1976 memoir False Starts, he was a bad crook, stumbling his way through reform school and into prison for capers that sometimes produced takes as low as thirty-five cents. As a result, Braly spent almost half of his life doing hard time in places like Folsom, San Quentin, and Nevada State prison.

Braly was eventually released in 1965 having already written the novels Felony Tank, Shake Him Till He Rattles, and It’s Cold Out There as an inmate. Legendary editor and agent Knox Burger, who had visited Braly in San Quentin and encouraged him to write, published all three for Fawcett in the popular Gold Medal line of paperback originals. But Braly’s best work, 1967’s On the Yard—celebrated by Truman Capote, John D. MacDonald, and Kurt Vonnegut—had to be finished in secret when prison authorities, nervous about potentially bad press, found out and threatened to overturn his parole. Braly went on to write False Starts and another novel, The Protector, but was killed in an automobile accident in 1980. (For more on Braly, read Brian Greene’s “Writing Behind Bars: The True Tale Of Noir Hero Malcolm Braly.”)

Frank Elli (1925 – 1984)

On March 30, 1966, the New York Times announced the winner of the $10,000 Thomas R. Coward award from publishers Coward-McCann: the unexpected winner was forty-year old Frank Elli for his prison procedural The Riot. What made Elli different than other contestants is that he’d been out of prison for barely more than a year and witnessed the true-life events of his novel at Walla Walla penitentiary while serving time for burglary. The stint was just part of a much longer rap sheet; over the previous two decades, Elli had been in prison 11 times for a combined 17 years in San Quentin, Walla Walla, and Minnesota’s Stillwater Correctional.

It was at Stillwater that Elli met up with the Ink Weavers, an inmate writing group, and began working on his craft every night after his work shift. With the encouragement of a University of Minnesota English professor, Elli went on to write The Riot, which won glowing reviews in the press and landed him spots on TV (The Mike Douglas Show) and radio (with Studs Terkel). The novel was quickly optioned for film and became 1969’s Riot starring Gene Hackman, Jim Brown, and the real-life warden and convicts of Arizona State Prison, where parts of the movie were filmed. Despite repeated attempts to recapture the success of his debut, however, Elli never published another book and in 1984 died of throat cancer at the age of 58.

Edward Bunker (1933 – 2005)

Born on New Year’s Eve, 1933, Edward Bunker was in and out of prison or on the run from age 14 to 42. While in solitary confinement in San Quentin (where, at 17, he was the youngest inmate ever admitted), he was placed next to the infamous death row inmate Caryl Chessman, who smuggled the young convict a copy of Argosy magazine. The issue featured an excerpt from Chessman’s best-selling memoir, Cell 2455, Death Row. Bunker, amazed that a con could write an entire book while locked up, never mind get it published, was inspired to do the same and wrote on and off for decades, losing whole manuscripts in the process of being jailed or fleeing from the law. His early first attempts evolved into the novel No Beast So Fierce, which became the movie Straight Time when Dustin Hoffman bought the film rights in 1973. After earning parole in 1975, Bunker managed to stay honest, eventually penning seven novels, multiple screenplays, and consulting on over twenty films. He was the inspiration for Jon Voight’s character Nate in Heat and scored cameos in over two dozen movies including Tango & Cash, The Longest Yard, and in Reservoir Dogs as Mr. Blue.

Albert Nussbaum (1934 – 1996)

Albert Nussbaum was a bank robber active in the 1960s and, at one point, a member of the FBI’s Most Wanted List. Nussbaum, bright and capable, was a chess player, mechanic, airplane pilot, and avid reader. He found the books of pulp writer Dan Marlowe especially true to life. When he wrote to Marlowe telling him so, the two struck up a friendship that persevered through Nussbaum’s 1964 arrest and 40-year sentence in Leavenworth. With Marlowe’s help, he turned to writing and his craft flourished. After his parole the early 1970s, Nussbaum turned out short stories for Ellery Queen’s and Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazines, wrote several novels, and even penned TV scripts for the CBS crime series Switch. He taught mystery writing workshops at USC and was active in the Mystery Writers of America SoCal chapter up until his death in 1996.

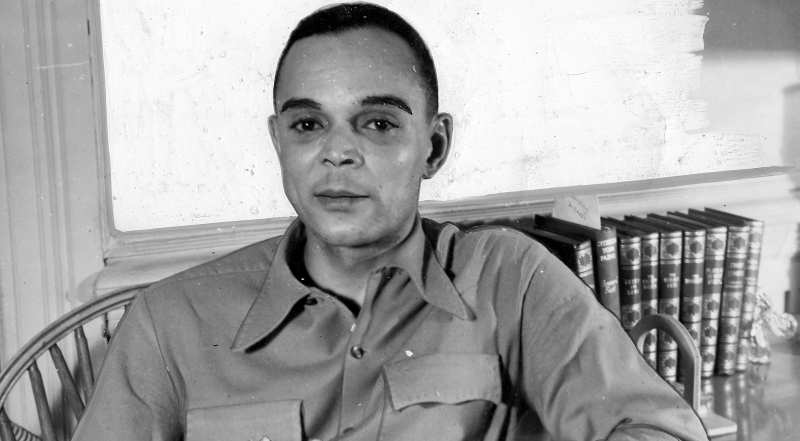

Emil Richard Johnson (1938 – 1997)

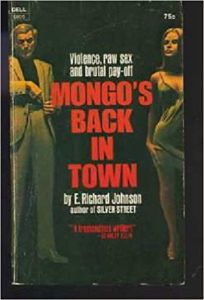

Richard Johnson, a former Army intelligence sergeant turned stick-up specialist, killed a man during a failed robbery and was sentenced to 40 years at Minnesota’s Stillwater Correctional Facility (where Frank Elli also did time). Johnson used the long hours to produce the first book in his Tony Lonto series, Silver Street (sometimes listed as The Silver Street Killer). The book went on to tie for the 1969 Best First Novel Edgar Award but Johnson, still serving time, had to accept the award in the prison visitors’ room.

Despite a life inside, Johnson’s star seemed to be on the rise with the publication of Mongo’s Back in Town, which became 1971’s made-for-TV movie Steel Wreath, starring Telly Savalas, Martin Sheen, and Sally Field. He managed to write several more novels before drug use, a prison escape, and a return to crime prior to his recapture destroyed what was left of his career. He was released from prison in 1991 but never published again.

Anne Perry (1938 – )

The bestselling author of the Thomas Pitt and William Monk detective series was originally born in England in 1938 as Juliet Hulme. Suffering from tuberculosis as a child, she was sent to the warmer climate of Christchurch, New Zealand to recover where she forged a friendship with a girl named Pauline Parker. Hulme’s parents were in the midst of separating, however, and planned to send her away to South Africa to live with a relative. The teens did not want to be parted and conspired against Parker’s mother, Honora Rieper, who they believed would not let Pauline join Juliet.

The two attacked Rieper in a local park, hitting her with a half-brick wrapped in a sock more than twenty times, killing her. As minors, the girls could not be sentenced to death under New Zealand law and were instead given five years in prison before conditional release. Afterward, Hulme rejoined her father in England, changed her name to Anne Perry, and worked various jobs in the United Kingdom and U.S. before publishing her first novel, The Cater Street Hangman, in 1979. Perry has gone on to write more than one hundred novels that have sold over 20 million copies worldwide. The story of her early life was the subject of Peter Jackson’s 1994 film, Heavenly Creatures.