“These days I look like what I am. A graying, aging jock with bum knees and a busted nose that never properly healed. Flaming migraines that singe my skull and a heart that hippity-hops out of tune. And yet, here I am, along with the wondrous Melissa, bit players in the great cosmic mystery of love.” – Jake Lassiter in Early Grave

No one is immune to the ravages of time…except for protagonists in crime fiction, and even then, with a few keystrokes, the writer can age, retire, or even kill your long-time favorite character.

Writers have several choices. Keep the hero the same age, no matter how long the duration of the series. Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe stayed 56 years old – and 272 pounds – through 70 books spanning 41 years. These days, a writer might be inclined to put Wolfe on the South Beach diet, lest he keel over in the middle of a case.

The hero can age gracefully, a feat readers (and writers) can only envy. Sue Grafton’s iconic P.I. Kinsey Millhone appeared to age seven years – from 32 to 39 – in the 25 “alphabet” books published over a 35-year time span.

The writer also can march the hero through life in close to real time. John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee was about 30 in The Deep Blue Good-by in 1964 and 52 when last seen in The Lonely Silver Rain in 1985. In A Deadly Shade of Gold (1965), McGee described himself as “that big brown loose-jointed boat bum, that pale-eyed, wire-haired girl-seeker, that slayer of small savage fish, that beach-walker, gin-drinker, quip-maker, peace-seeker, iconoclast, disbeliever, argufier, that knuckly, scar-tissued reject from a structured society.” Twenty books and 21 years later, his reflexes are not as quick, his joints ache, and it takes warmer baths or more gin to heal the wounds from his most recent scrapes.

Scott Turow’s trouble-prone lawyer Rusty Sabich also aged with the times. Sabich was 39 in the 1987 blockbuster Presumed Innocent and reappears two dozen years later as a 60-year-old judge in Innocent. Sabich was charged with killing his mistress in the former book and his wife in the latter. Unlucky in love doesn’t begin to describe his predicaments.

Representing Sabich in both tales is Alejandro (Sandy) Stern, a slick and wise defense lawyer. By the time Innocent rolls around, Sabich is feeling his age, and Stern is suffering from lung cancer and undergoing chemotherapy.

The prolific Lee Goldberg takes a different approach with his hit series featuring L.A. detective Eve Ronin. The first four novels (Lost Hills et al) were published over three years but take place in a compressed six months on the page.

“Eve is aging, but very slowly,” Goldberg says. “I created a character who’s young, raw and inexperienced as a detective but has a natural talent for the job. Over time, we’ll see her mature into the self-confident, super-sharp cop who is usually at the center of police procedurals.”

So what to do? Do readers really want to accompany their heroes to the doctor’s office for cataract surgery or a colonoscopy? Should writers sweat bullets creating suspenseful waiting room scenes complete with ancient People magazines and network game shows, sotto voce, on the overhead television? Or should crime fiction be an escape from the mundane (and tragic) realities of our lives?

My vote is that our heroes shouldn’t appear to be immortal. It’s enough that they frequently escape death by their wits and maybe their fists. How about a dose of reality that readers recognize in their own lives or those of family and friends?

My Jake Lassiter series began in 1990 with To Speak for the Dead and concludes fifteen books later with the newly released Early Grave. Lassiter, a linebacker-turned-lawyer, has aged about two-thirds of those 33 years and has ailments and personal problems galore. His late-in-life relationship has hit a rough patch, and he’s in couples therapy with his fiancée in the new novel. His godson has suffered a catastrophic injury in a football game, and Lassiter becomes the most hated man in Miami when he sues to abolish high school football. Worst of all, my hero appears to have CTE, the fatal brain disease caused by repetitive head injuries.

In To Speak for the Dead, Lassiter was in his late thirties, a rugged man whose neck was always threatening to pop the top button of his dress shirt. With his broad shoulders and solid jaw, he was an imposing figure in the courtroom: “I stood there, 230 pounds of ex-football player, ex-public defender, ex-a-lot-of-things, leaning against the stained oak rail of the witness stand, home to a million sweaty palms.”

Thirteen novels later in Bum Luck (2016), Lassiter appraised himself: “My shaggy hair, once the color of Everglades sawgrass bleached by the sun, is going gray. Not the distinctive silver-fox gray of those handsome, crinkly-eyed dudes in Viagra commercials. More like cigar-ash gray. My face, now craggy as Mount Rushmore, had once attracted fishnet-stockinged groupies in low-end cities of the AFC, primarily Cleveland and Buffalo. I’ve never been married, and with slim prospects these days, I sleep alone.”

Fortunately for Lassiter, later in Bum Luck, he meets Dr. Melissa Gold, a neuropathologist who both diagnoses his medical condition and later becomes his fiancée. Two years later, in Bum Deal (2018), he reminisces about their bittersweet meeting:

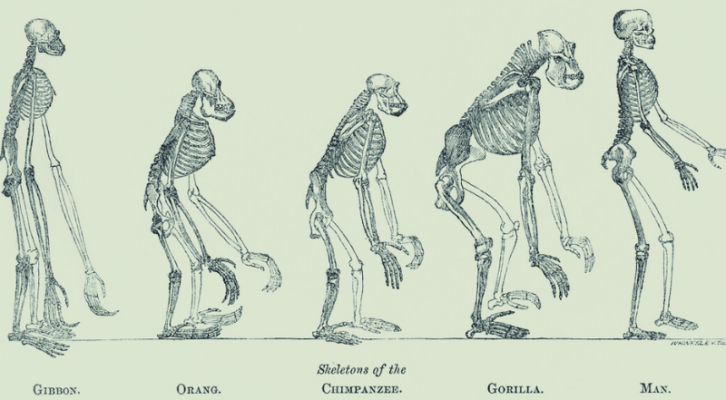

“In California, I had taken Dr. Gold out to dinner where I performed the charming stunt of fainting, face-down, into a platter of smoked pork bellies with roasted blackberries. This came after several weeks of piercing headaches and a few episodes of confused behavior and short-term memory snafus. My symptoms were consistent with several very scary illnesses. Senile dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, and, of course, CTE. They’re pretty much first cousins of each other. Nasty, homicidal cousins. My first brain scan’s results were ‘murky,’ to use Dr. Gold’s word. I had some misshapen tau protein that she called a ‘precursor’ to the incurable disease. I took this to mean that the Grim Reaper had been spotted in my neighborhood but hadn’t yet rung my doorbell.”

Ask not for whom the doorbell tolls, old buddy. It tolls for thee, for me, and for everyone.

Like a lot of men of a certain age, Lassiter doesn’t like to admit he’s ill or in pain. When his fiancée realizes he’s downplaying his ailments in Early Grave, she becomes frustrated with him.

“You’ll tell me you’re fine when you’re fighting a migraine, or your tinnitus is as loud as a freight train,” Melissa said.

“Actually, it’s more like a hurricane ripping metal street signs in half.”

“That’s better. Just be honest with me, Jake.”

“Whenever I feel like whining about the small stuff, I think about the guys who are no longer with us.”

“You’re talking about the Miami Dolphins,” she said.

“Six from the 1972 Super Bowl team. Dead from CTE. Perfect season, my ass!”

I would tell you more about the aging of my fictional hero, but my own tinnitus is acting up, a cacophony of drums and bugles. Plus my lower back is sore from sitting hunched over the keyboard, and it’s time to ice my knees so I can walk to CVS and pick up my prescriptions. Still, much like Lassiter, I won’t whine about the small stuff.