When I was fourteen years old, much to the annoyance of my parents, I would only read one type of novel: the ones that were written by Agatha Christie. My mother used to nag and/or bribe me to read more upmarket fare, and actually I was busted, around the same time, having pocketed the prize money, for claiming to have finished Jane Eyre and then ‘not remembering the bit’ about Mrs Rochester. I am still teased about it today—but that is another story.

Attempting to defend the quality work of Agatha Christie, my teenage self told my far-from-stupid mother that I had been moved to tears while reading Death on the Nile, due to the amazing character development of its various murder victims. This was an obvious lie, and she roared with laughter. I realize now, of course, that I was coming at the thing from the wrong angle.

The point is (and I’m getting there) it is virtually impossible, when reading a halfway decent mystery novel, not to groan and throw the book across the room when you reach the final page. In fact the more compulsive the journey towards finding out who dun the dirty deed, the more infuriating tends to be the revelation, and the more foolish the reader feels for ever having been dragged into the sorry affair in the first place. At any rate, as a woman who has frittered many hours—days, weeks— years—powering through old fashioned murder mystery novels—Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, GK Chesterton, Conan Doyle, Margery Allingham—this is my experience. It is what I try to keep in mind while writing my own murder mysteries.

Who dun it doesn’t really matter—as long as their identity delivers the right level of surprise (it shouldn’t be too preposterous) and there are no holes in the how and the why. In fact, for the story to work, it mustn’t really matter whodunnit, because—clearly—among the cast of characters in any mystery novel, some will have to get dun in, and some will have had to do the dunning. If a reader cares too much about the victims, it ruins the sport of finding out who murdered them.

The trick, then, is to ensure that the inevitable book-closing groan-and-throw is accompanied at very least by an affectionate shake of the head—and at best, by a hearty chuckle. This requirement is more important now than ever, and far more important than it was during the more innocent, golden age of mystery writing. Fiction readers, like cinema audiences, are an increasingly savvy crowd. Murder mysteries (which are of course quite different from thrillers) need to evolve if they are to stay ahead of their readers. In today’s smartypants world, there needs to be a tacit acknowledgement, between mystery author and sophisticated mystery reader, of the genre’s intrinsic absurdity: an understanding that author and reader are both in on the same joke. And it is a joke.

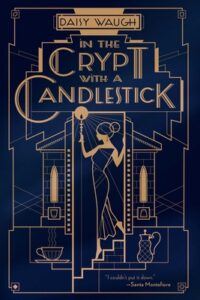

When I write, I like to imagine I am writing for a friend—someone humorous, intelligent, and not too uptight; someone I wouldn’t mind spending an evening getting drunk with. I write murder mysteries—of increasing absurdity—under two names. As EV Harte I write about a London-based professional tarot reader who keeps encountering potential murderers and victims in her consulting booth. Under my real name, Daisy Waugh, I write about aristocrats murdering each other in posh houses. In the Crypt with a Candlestick, which has just been published in America, has an aristocratic ghost, Lady Tode, helping the murder inquiries along. Old School Ties, which I am in the middle of writing, has not one ghost but two—the second being Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), the distinguished water engineer. Which is all well and good. At the very least, I laugh aloud while I am writing it.

***