When I took the GREs after a lonely year of post-college soul-searching, I immediately went out and rewarded myself with the Library of America collection of David Goodis novels, headed to Spiderhouse Cafe, and spent several enjoyable hours reading the book before I spilled half of a Mexican martini on the gorgeous new edition and permanently wrinkled the last hundred pages. David Goodis wouldn’t have minded, though—he was the rare individual that could witness people at their worst, never looking away, and still understand individuals as subject to both their own foibles and the arbitrary demands of an uncaring system.

David Goodis was born in Philadelphia on March 2, 1917, the child of an immigrant father and a first-generation American mother determined to give him a middle-class upbringing and college education. Despite his relative privilege, Goodis was determined from the get-go to sympathize with the downtrodden, the oppressed, and the outsider, embracing the language of noir as a vehicle for social criticism even as he focused on portraying human foibles. Ever conscious of his Jewish identity, he lived through the peak of anti-Semitism in the US (which cut off abruptly in public life during WWII, but has remained an undercurrent in American life to the present day), and his defeated and fatigued characters have as much in common with Old World Jewish literature as they do figures in noir. He also lived and loved in a segregated city, rejecting potential happiness with black girlfriends so as to not upset his parents, whose own outsider status certainly didn’t preclude prejudice against others. He ventured forth to Skid Row and wandered around slums, transforming his observations into noir fantasies.

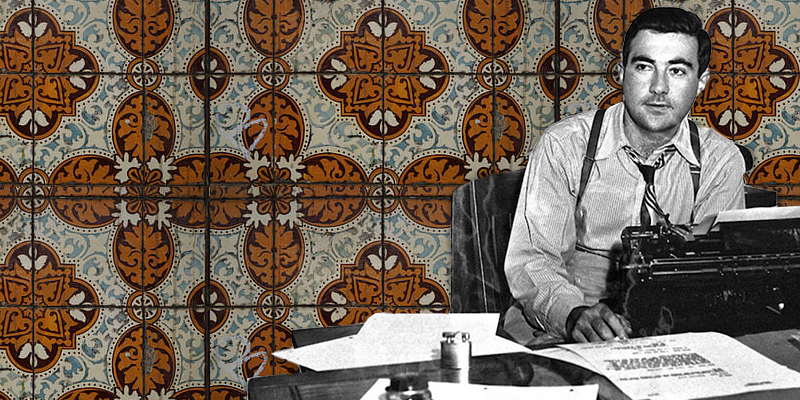

Photographs of Goodis reflect a nervous, rumpled character—he’s handsome, but he’s torn. He’s not going to do anything, but then again, he’s not going to look away, either. When I look at pictures of Goodis, I see myself in him. Not in his beautifully wrought sentences or cutting observations. But in his need to witness, and his refusal to smooth his shirt.

After getting a degree in journalism in 1938, Goodis worked briefly in advertising while also writing for the pulps. His first few books never took off, but 1946’s Dark Passage, both as a book and a quickly adapted film, brought Goodis to the fore of American noir writing. Throughout the 1940s, he split his time between New York City (where he wrote for the pulps) and Hollywood (where he wrote for the studios), before burning out and returning to Philadelphia in 1950. There, he would reside, taking care of his schizophrenic brother and aging parents, and churning out the decade’s most depressing pulp fiction, until his death at age 49 on January 7, 1967. He died of a stroke while shoveling snow, possibly caused by his resistance to an armed robbery a few days earlier. His death reflected an essential truth about humanity that he understood all too well: don’t write someone off, just because they’ve given up; there’s a flicker of resistance in all of us, hidden among the tumult of guilt and shame.

It’s difficult to find quotes from David Goodis about his own approach to writing, but the accolades and insights of others help fill the gap. Ed Gorman once said that “David Goodis didn’t write novels, he wrote suicide notes,” and if we think of the literature of the suicide note, filled with equal parts anguish, guilt, love, and attempts to understand, then David Goodis’ work would easily fit within these bounds. His characters are broken down shadows of their former selves, worried more about damaging those they love then worrying about damage to themselves; as full of weaknesses, contradictions, and surprising resistances as Goodis himself.

When Goodis died, his work had fallen out of print in the United States. The French carried the torch for Goodis’ work, as well as adapting several of his novels, until reissues in the 1980s restored David Goodis to the noir canon. The 60s and 70s, times of change and even occasional optimism in the US, didn’t really need Goodis anyway—it’s our current late-stage capitalist empire that can most benefit from the warnings in his words, and most needs the reminder of humanity that his novels can best provide.

In honor of David Goodis’ birthday, we decided to round up the author’s bleakest and most beautiful reflections on humanity, all drawn from his noir oeuvre.

Being Human is Hard

“The trouble with people is they don’t understand people.”—Nightfall (1947)

Women Can Be Complicated, Too

“He told himself she wasn’t really such a bad person, she was just a pest, she was sticky, there was something misplaced in her make-up, something that kept her from fading clear of people when they wanted to be in the clear.”―Dark Passage (1946)

“Her features were thin and her skin was pale and she was certainly not pretty. But it was an exciting face. It was terribly exciting because it radiated something that a man couldn’t see with his eyes but could definitely feel in his bloodstream.”―Street of No Return (1954)

“There’s nothing fragile about this one. That ain’t a fragile nose or mouth or chin, and yet it’s female, more female than them fragile-pretty types who look more like ornaments than girls.”―Shoot the Piano Player (1956)

At the End of the Day, We’re All Alone (and Also We’re All Losers)

‘”It’s just that I’m curious, that’s all. He usually walks alone.”

“Yeah, he’s a loner, all right,” the waitress murmured. “Even when he’s with someone, he’s alone.”‘―Shoot the Piano Player (1956)

“You know me. Guys like me come a dime a dozen. No fire. No backbone. Dead weight waiting to be pulled around and taken to places where we want to go but can’t go alone. Because we’re afraid to go alone. Because we’re afraid to be alone. Because we can’t face people and we can’t talk to people. Because we don’t know how. Because we can’t handle life and don’t know the first thing about taking a bite out of life. Because we’re afraid and we don’t know what we’re afraid of and still we’re afraid. Guys like me.”―Dark Passage (1946)

“I lost my spinal column a good many years ago. There ain’t no surgery can put it back. Even if there was, I wouldn’t want it. I like it better this way. More comfortable.”―Street of No Return (1954)

Dreams are Hard to Come By, Memories are a Dime a Dozen

“A cat came out of an alley, took a look at all the snow, and went back in. Farther on up the street a fat man, aproned and puffing, emerged from a restaurant and whiffed the cold air and gazed yearningly at the sky. As though even the dreams were up there, much too far away.”―Of Tender Sin (1952)

“He moved on down the alley, his feet walking forward and his brain swimming backward through a sea of time. It was a dark sea, much darker than the alley. The tide was slow and there were no waves, just tiny ripples that murmured very softly. Telling him about yesterday. Telling him that yesterday could never really be discarded, it was always a part of now. There was just no way to get rid of it. No way to push it aside or throw it into an ash can, or dig a hole and bury it. For all buried memories were nothing more than slow-motion boomerangs, taking their own sweet time to come back. This one had taken seven years.”―Street of No Return (1954)

The System Is Out to Get You (Or, Just Doesn’t Care)

“I think the way to stop it is to shrug it off. Or take it with your tongue in your cheek. Sure, that’s the system. At any rate, it’s the system that works for you. It’s the automatic control board that keeps you out there where nothing matters, where it’s only you and the keyboard and nothing else. Because it’s gotta be that way. You gotta stay clear of anything serious.”

―Shoot the Piano Player (1956)

“The police, he told himself, were marvelous when it came to just standing there. Sometimes they elaborated on it a little and pushed their caps back and forth on their heads. Nobody could push a cap back and forth on his head like a policeman.”

―The Burglar (1953)

Sex Is Private (And Occasionally Rather Perfunctory)

“It was very fast, that first time. They were on the couch, and then they were off the couch and it was all over. It was like jumping out the window and landing on the street. A quick ride, just like that.”―Of Tender Sin (1952)

“You’ve really earned it, he thought. You’ve played a losing game and actually enjoyed the idea of losing, almost like them freaks who get their kicks when they’re banged around. You’ve heard tell about that type, the ones who pay the girls to burn them with lit matches, or put on high heeled shoes and step on their faces. That kind of weird business. And it’s always the same question. What makes them that way? But you never took the trouble to figure the answer. What the hell, it was their private worry, it didn’t concern you.”―Street of No Return (1954)