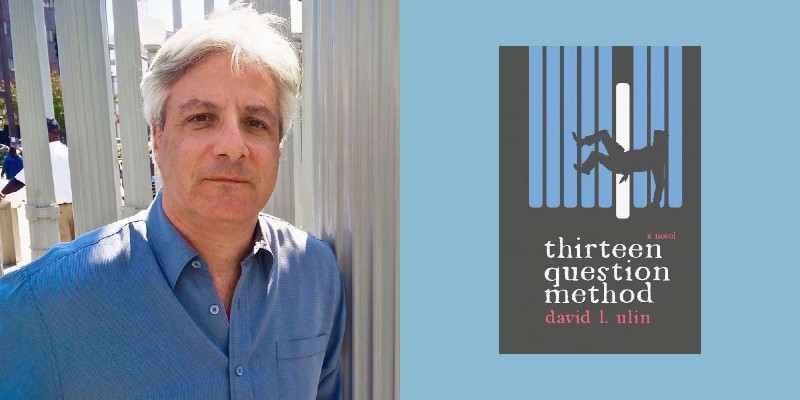

David L. Ulin has spent the better part of thirty years as the preeminent book critic in the West; first at the late, great, LA Reader and then as book review editor and later Book Critic for the Los Angeles Times and currently as the books editor for Alta Journal. At the same time, he’s published several critically acclaimed nonfiction titles, including Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles, The Myth of Solid Ground, and The Lost Art of Reading: Why Books Matter in a Distracted Time, picking up a Guggenheim, a California Book Award, and inclusion in Best American Essays along the way.

Don’t worry. You’re not on the wrong page. This isn’t NonfictionReads.

Because David L. Ulin has been quietly setting the stage for a career in crime writing for years, including his turn editing Cape Cod Noir for Akashic in 2011, devouring the classics along the way. The result is Thirteen Question Method (borrowing its title – and structure – from a classic Chuck Berry rave-up that asks, optimistically, “Do you want to have some fun?”), which finds Ulin’s nameless narrator alone in his Los Angeles apartment during wildfire season, listening to the evening screams of his neighbor Corrina. Soon enough Corrina comes by, looking for a favor, the kind you pay $200 bucks for in a novel like this, and Thirteen Question Method is off.

The novel is a bullet – it’s a true one-sitting book, clocking in at a brisk 169 pages that somehow are both dense and entirely fluid – and Ulin has captured the Los Angeles of noir dreams: a violent, desperate place filled with bad people doing worse things. It’s also a novel only a man who has literally walked all the streets could write: David is a master of minutia, the tiny telling-detail that reveals something larger about the world we’re in, or something smaller and more insidious, or both. I should note that David and I are old friends and colleagues which is fortunate for me, since otherwise I’d have to send him a fan letter. We caught up a few weeks before the novel’s release.

Tod Goldberg: The opening sentence of your novel – “The woman across the courtyard was screaming.” – drops the reader immediately into one of the darkest noir novels of this young century and yet it feels somehow like a piece of historical fiction, too. As if it’s a missing piece of LA noir that was just discovered in an old grocery bag inside a suitcase at a bus terminal. I have to presume that was intentional. To both be fresh and new but also remind readers of the Golden Age?

David Ulin: Like everything, it was intentional and not intentional. Or: unintentional until I figured it out. This novel, or the basic idea of it, lived in my imagination for a long time before I began to get it on the page. At some point, way back in the mid-1990s — when the book was just a kernel of an idea: a title and a set-up — I was hanging out at a friend’s place near Marshall High School. We played softball together on Saturdays, and often, we’d end up back in his living room, drinking a few post-game beers. He lived in a bungalow court, and one afternoon, one of his neighbors started screaming. I was concerned: Was this the usual? Should we try to help? My friend assured me that it was a common occurrence, that this neighbor screamed all the time. I remember sitting in his bungalow, listening to her, and literally thinking: There’s my first line.

The intent of the novel, or one of them, is to inhabit the territory of classic noir while also being contemporary. So once I started writing, that was a balance I consciously sought. I wanted the book to be both timeless and of its moment, not an homage exactly (although that, too) but a continuation of sorts. The darkness at the center of it, after all, is – to me, anyway – the most common and prevalent of human states. It never goes out of style.

TG: You’ve had a long and distinguished career in nonfiction – from your time as a book critic and editor at the Los Angeles Times to your standalone essays and of course books like Sidewalking and The Myth of Solid Ground and beyond. What made you decide to shift gears so dramatically and dive into a noir novel?

DU: It wasn’t exactly a conscious process. As I said, the novel incubated for quite a while. I got the initial impulse in the late 1980s when I was really discovering and immersing in noir for the first time. I had read Raymond Chandler, of course, and also Dashiell Hammett, and I had read Camus (who is not a crime novelist, but also sort of is; The Stranger, famously, was influenced by James M. Cain.) Thirteen Question Method is also inspired by Cain; early on, I thought of it as Triple Indemnity, because I knew from the start I wanted that extra layering: two antagonists, who were also antagonists to one another, a step-mother and step-daughter in an inheritance dispute. I didn’t know exactly what would happen, but I knew the narrator would have to choose between them, and that he would choose wrong. That became more complicated and weirder as the book took shape, and went in directions I couldn’t have hypothesized before I started to write. So yes, it is a departure of sorts, I suppose, but it doesn’t really feel that way to me since I’ve been living with it for so long.

Noir, once I immersed in it, changed a lot for me. I was attracted by the bleakness, the existential desperation. I was attracted by the idea that, in the noir I most admire, there is no redemption and nobody wins. That feels to me a lot like what it is to be alive, the specter of our own negation, our own disappearance always hanging over us. I wanted to write a book that was uncompromising, that didn’t give the characters, or the reader, an easy out. So much of the crime fiction I read comes right up to the edge of that but then pulls back at the last moment. I didn’t want to do that. Among my models were Charles Willeford (especially High Priest of California) and everything by David Goodis. Dorothy B. Hughes’s In a Lonely Place and Chester Himes’s If He Hollers Let Him Go. The romans durs of Georges Simenon, particularly Red Lights and Dirty Snow. In recent years, I’ve read a fair amount of Japanese noir: Seicho Matsumoto’s Pro Bono and, of course, the work of Fuminori Nakamura, whose Last Winter, We Parted is as relentless a novel as I know. There are no false illusions in any of that work. This was the territory to which I was drawn.

TG: So much crime fiction is bulky and over-written, however the style you’ve chosen for Thirteen Question Method reminded me of everyone from Albert Camus to Jim Thompson – which is to say: spare and dark but with a hard-won intelligence – and yet it is uniquely your own. There’s a twinkle of your sardonic sense of humor throughout, which serves as needed relief. Did you wrestle with how to tell this?

DU: I knew all along that I wanted it to be taut. The bloated nature of so much crime fiction was something I wanted to push against. Again, this is in part because I wanted to honor, and work, in the classic noir tradition. I wanted a reader to be able move through the book in a single sitting. In fact, I wanted that, to catch the reader up in the narrator’s fever dream. My favorite noirs – the one cited above and many others – are, to borrow Thomas Hobbes’s description of life, “nasty, brutish, and short.” I loved the economy. Jim Thompson’s books, as you note, are almost all less than 180 pages. The Stranger is shorter than that. The narrative of Thirteen Question Method takes place over a couple of weeks. The novel is tightly constrained in terms of the number of characters (three, really, with a few walk ons) and setting. I wanted to get in and out.

The biggest challenge for me was plotting because in nonfiction, you live the story first. Here, I had to make it up as I went along. That took some time also; I wrote the first 75 pages of the novel in the summer of 2015, until I got the narrator into a situation I couldn’t figure out how to get him out of. I had no choice but to put the novel down. I started working on another book, a memoir, but I always knew I wanted to come back to this. Then, at the beginning of lockdown, when everything seems so much about the present tense, I found I couldn’t work with memory. So I set the memoir down and re-read the novel pages and saw where the narrative ought to go. I finished a draft in four months after that. It took on a life of its own.

One more thing I ought to say here is that, as with many of my books, I constructed games or guardrails, structural conceits to carry me through. The book is called Thirteen Question Method and it has thirteen chapters. Each chapter has thirteen pages. I like the symmetry of that, but also, for someone working in a new genre, it was useful to have that idea of length, of what I was writing toward. It helped keep the narrative on track.

TG: I’ve always thought that the best noir fiction acts as a response to some key aspect of our culture. Here, your unnamed narrator has, shall we say, a fungible sense of reality. To write what is ostensibly a mystery when our guide through the story isn’t always tethered perfectly to this world brings into question the very notion of truth and fact, which is a perfectly analogous to this current life we’re living in, where everyone has their own truths, if not facts. Are you thinking of things like this when you’re sitting down to write or is it simply a function of being alive – you can’t avoid what’s floating around you?

DU: I think it’s a little bit of both. Certainly, it’s impossible to avoid what’s floating around me. Writing the bulk of the book during lockdown led me to really dig in on the question of isolation, perhaps in a different way than I would have if I hadn’t been isolated myself. I didn’t want to put the pandemic in the novel, but certainly there are themes of contagion and virus and infection and distance laced throughout the book. The narrator wears a blue suit with a long red tie when he goes on his … inquiries, and that was certainly a conscious echoing. As for the unreliability of the narrator, that was baked in from the outset. It was less a commentary on fake news and competing truths than a reflection of my belief that every narrator is unreliable. Every story that’s told has an agenda. As for what that is, it depends on who is relating it. Writing from the perspective of an unreliable narrator was liberating because it means I could operate outside the bounds of a common, shared reality. I could let his obsessions, his fantasies, define the terms. It got really interesting in the last half of the novel, when he effectively loses touch with what is happening outside his own head. We’ve all been there in one way or another, but I wanted to explore the extremity of his circumstance.

TG: Reading your book firmed up something in my mind that I’ve been pondering for a bit: There’s a difference between the kind of crime writing happening in the West than anywhere else in the country. Maybe the world. There’s a brimming sense of menace just in the way you describe the weather – “[T]he sun was a sledgehammer” for instance – that gives an edge to every scene, because even the sun wants you dead. What is it about the West, and LA in particular, that lends itself so easy to crime?

DU: Mike Davis called it the sunshine/noir dialectic, which I think describes the dynamic neatly: the idea that in a place like this, which is built in many ways on a kind of paradisal mythos, the flip side – the despair of failure – hits particularly hard. In part, I think it grows out of the old (and in some ways outdated) trope of Southern California as a destination, as a landscape of reinvention, where we come to find, or access, our better selves. In such a construct, what do you do when things go wrong? You can’t go home again, so you are stuck. More broadly, I think, this is true of Los Angeles because of the vast disparities between the haves and the have-nots, the way glitz and glam and wealth and excess are always visible to us, even if they are effectively out of reach. So that’s a recipe for menace and for mayhem. And for existential desolation, which is for me the beating heart of noir.

Then, of course, there is the elemental nature of the place, the floods and fires and droughts and earthquakes, the inhospitality of the landscape itself. I’ve been obsessed with that for more than thirty years, ever since I got here: the fact that in a land mythologized as edenic, nature is always waiting to wipe you out. That’s why I wrote The Myth of Solid Ground, about earthquakes, and it’s a big part of the wildfire component in the book. We are always raw here, or the place is, and the elaborate constructions we develop about speed and light and comfort are just lies we tell ourselves to get through the day. That, too, seems to me deeply connected to the ethos of crime fiction, which often involves people fooling themselves. When a place promises as much as this one does, it’s a huge comedown when those promises fail to materialize, whether because of nature or our own misfortune. I think that sensibility is the sensibility of Southern California, and noir is the representation of that idea.

TG: Now that you have the bug…I presume you’re hard at work on something equally dark and disturbing? Can we expect that this is not a one off?

DU:The honest answer is that I don’t know. I’m deep in the middle of another book now – the memoir I set aside at the beginning of lockdown – and I have a couple of ideas for what I might do after that. But really, I’m a one book at a time writer. It’s too hard for me to map out what I might be working on at some point when I am working on something at this point. So I will have to see when I am done. But whatever I do will be infused with this sort of existential conundrum, which to me is the essence of meaning … or its lack. We create stories to give shape to the chaos of existence. They sustain us, if we’re lucky, until they no longer can. They cannot save us. Death is coming. There will be disruption and despair. That idea sits at the center of everything I have ever written and (I have to imagine) everything I will ever write. It is how my heart and my imagination are wired.