Ten years after its publication in 1940, the literary critic Edmund Wilson sent his then-friend and future enemy Vladimir Nabokov a copy of The Big Con by David W. Maurer. It was just one of a batch of books Wilson thought Nabokov would find interesting, but Maurer’s chronicle of professional con men, their best-known swindles, and their specific argot, stood out. Wilson, in his March 1950 letter to Nabokov, called The Big Con “a very curious book by an authority on the underworld … It throws a good deal of light on certain aspects of American life.” Wilson was certain that Nabokov would take to the “incredibly funny stories … especially about pickpockets and such people who unsuccessfully aspired to be confidence men.”

If Nabokov did take to The Big Con, he never said so in writing. His immediate reply to Wilson, a few days later, opened with ribald amusement—“For one instant I had the wild hope that the big Con was French”—easy innuendo (for con translates as “c__t”) doubling as a shield from further discussion. But like the Nabokov scholar Barbara Wyllie, I’m inclined to believe Nabokov paid some heed to The Big Con, because he and Maurer were very much literary kin: men plumbing the depths of English language and argot for secrets, other people’s as well as their own. Men fascinated by criminal underworlds, spelunking through the deepest crevices while remaining at a cool, academic distance.

Nabokov would hardly have been alone in gleaning literary influence from The Big Con. Eight decades on, Maurer’s work is stamped all over American culture. Confidence men (and women) abound, all the way to the upper echelons of government. The “Summer of Scam” shows no sign of ending, seasons be damned. The American Dream masquerades as Multi-level Marketing.

David Maurer, as I discovered, fashioned a skeleton key. To unlock it, I had to do more than read his work, but find out why he was so attracted to criminal minds—and at what cost.

***

Caring about language requires an ability to listen. And that is something young David Warren Maurer (1906-1981) developed early, as a boy growing up near New Philadelphia, Ohio. He was a brilliant student from the first, graduating first in his high school class in 1924, then with honors from Ohio State University, whose English department hired him as professor in the fall of that year.

But even as Maurer rose through the academic ranks, he gravitated to those far less bookish than he. His physical appearance helped: a former student of his, Stuart Berg Flexner, described Maurer as “big, with large shoulders and strong arms and hands, a man who can help pull in a heavy fishing net in freezing weather.” (His friend and former assistant, Allan Futrell, was pithier, calling his mentor “a cross between Colonel Sanders and Ernest Hemingway.”)

This macho bearing served Maurer well when he found himself among fishermen folk in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland during the summer of 1929 (perhaps even during his honeymoon with his first wife, the former Ruth Schneider, herself a teacher and Oxford graduate). While watching fishermen oversee their boats off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, Maurer started listening to their speech cadences, to the peculiar argot that developed among them, and only them.

It wasn’t that these men spoke differently from others with a more bookish bent or more education, it’s that they built a language among themselves, a marker of internal communication that invited only those who were meant to be invited. In other words: a subculture. And Maurer, while doing the physical work of trawling for fish, chopping wood, or spending time in the field, also did the mental work of taking note of how those around him talked.

Eventually Maurer published the results of his outdoor observations in a 1930 article entitled “Speech Peculiarities of the North American Fisherman” for the quarterly publication American Speech. It would be the first of dozens, an eventual column, tracking subcultures of all kinds—the criminal, the chaste, and much in between—all ending with a glossary of words and meanings that those peering into the subculture could never know, not until Maurer cataloged them.

A United Press wire story from April of 1932 reported that Maurer racked up a glossary of “more than 500 words, used by thieves, racketeers, and other underworld characters.” At that stage, said Maurer, criminal argot sprung up so that “conversations among hoodlums and prisoners might be more guarded.” And some of the slang Maurer wrote down still carries over today: “grease” for protection money; “box” or “crib” for a safe; “artillery” for firearms; and “moll” or “skirt” for women in the underworld. Maurer also decreed, based on his research, that Youngstown, Ohio had “the hardest collection of individuals I ever want to see.” Needless to say, this judgment did not go over well with the local police, whose chief vowed to clean up the city and beef up the force, even as he protested: “there hasn’t been a gang killing in over a year.”

The following year, in 1933, Maurer began his parallel pursuit of slang from narcotics users, publishing his initial results in American Speech. A “sleigh ride” was a coke high; “kicking the habit”—still very much used today—describes attempts to break free of addiction. A “speed ball” was a “shot in the arm” into the “main line,” describing drugs injected into a primary vein. Attention on criminals and drug users, Maurer explained at various points then and later on, owed to “mental recreation from a dull and respectable PhD thesis.”

Recreation turned out to be a calling. Maurer earned his PhD in 1935. He would also marry a second time. Maurer had become a widower when Ruth succumbed to tuberculosis in November 1933, after a year spent quarantined in a sanatorium. Barbara Starbuck was an undergraduate at Ohio State University, a student in Maurer’s English class. Several articles reported a consistent story: Barbara, at some point, talked back to her professor. This piqued Maurer’s ire and his interest, sparked some sort of mutual attraction, and not long thereafter, the two married.

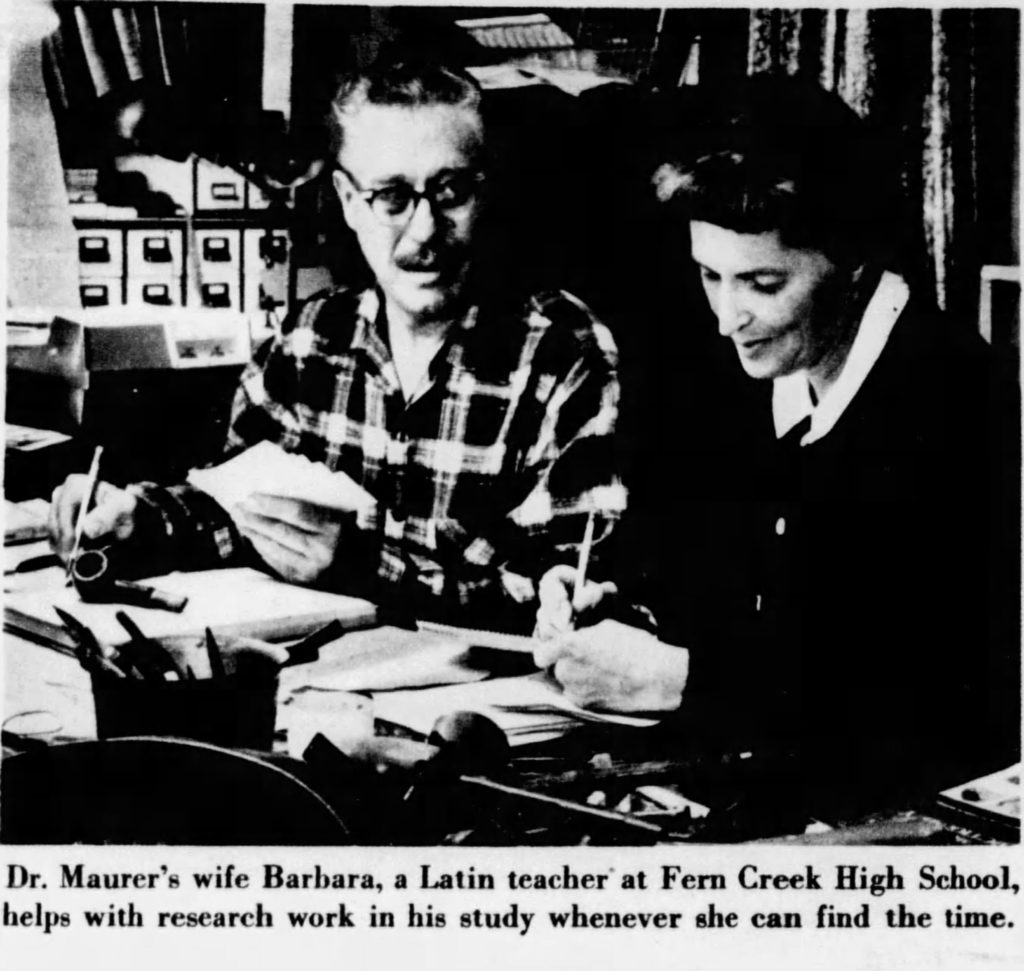

1964 photo of David and Barbara Maurer (Louisville Courier-Journal)

1964 photo of David and Barbara Maurer (Louisville Courier-Journal)

“The Countess,” as Maurer memorialized his wife in the glossary to The Big Con, proved indispensable to him. She typed up his dictated notes and his interviews. She tended the garden, froze and canned its fruits, and baked sweets so tasty they were written up by the local paper. She entertained visitors, whether they were Maurer’s students or writers like H.L. Mencken and Clayton Rawson. Barbara, naturally, also did the brunt of childcare for their only daughter, Joann, born in 1948. All this while working as a teacher at Fern Creek High School in Louisville.

After his marriage and newly PhD-minted, Maurer joined the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Louisville, his domestic and intellectual home for the next four decades While there, he would teach students, who lionized him. He would delve further into the speech habits of drug users, the history of moonshiners, the ways and means of pickpockets, and publish untold books and articles on all.

But there was something about the professional criminal, the con man, that attracted Maurer most and made his reputation. And as a Phony War raged in Europe and the Great Depression neared an end, Maurer’s by-product of his academic research came into being. Because, as he would tell an Associated Press reporter in 1948, criminal argot was “part of the English language. Leaving it unstudied would be like leaving a part of the world unmapped.”

***

The Big Con stands out from Maurer’s other writings because it was not intended for an academic audience. Maurer, in the introduction, called the book “a by-product of linguistic research,” though its lively writing style clearly shows it’s a lot more than that. It’s journalism because Maurer never paid the criminals and con artists who supplied him with information (though he did slip them “tobacco money” if they were incarcerated, so that they might buy books, magazines, even typewriters, to better communicate and lessen boredom) and because he took care not to appear “as an apologist for the criminal.”

Even stepping aside and ceding the narrative floor entirely to the criminals and con men, Maurer can’t help but invoke a little bit of razzle-dazzle. Because—and this is why readers can’t get enough of such stories—con artistry is entertaining. A con man, Maurer writes, “must be able to make anyone like him, confide in him, trust him.” It’s theater of the miniature, designed to attract a would-be mark, reel them in, hook them on the line, and then, when it’s clear the mark will pay up, blowing them off after the money disappears.

Confidence men didn’t have to be intellectual, but they had to be clever, and cunning, and sense weakness in potential marks like predators sniff blood from prey.Confidence games required care and work; you can’t just set up a “Big Store” out of nothing. Confidence men didn’t have to be intellectual, but they had to be clever, and cunning, and sense weakness in potential marks like predators sniff blood from prey. Some of those prey were repeat victims, as Maurer discovered to his astonishment: “the rather remarkable but well-established fact is that men who have been beaten once will come back again—and again, and again. Truly, ‘you can’t knock a good mark.'”

And what con artists like Joseph “Yellow Kid” Weil (who later went on to write, with W.T. Brannon, an entertaining if embellished 1948 memoir of his own) or the Yenshee Kid or the Hashhouse Kid knew is that “the higher a mark’s intelligence, the quicker he sees through the deal directly to his own advantage.” It’s why Yellow Kid, in particular, disdained marks as fellow criminals, usually in the upper society strata, looking to get something for nothing—and yes, that attitude is classic victim-blaming, but that’s the attitude one adopts to justify repeated swindles.

Once the narrative portion ends, Maurer then saves room for a glossary of con artist argot, the “artificial languages used by professionals for communication among themselves.” Here, and many times throughout Maurer’s career, he stressed that slang developed as internal lingo, a marker of subculture, instead of being a secret language intended to deceive outsiders. Without Maurer, we might have heard of phrases like “to bilk” (now generally used as a swindle, but then specific to a short-con game involving brothel owners) or “blow off” or “the sting” (more on that later) but we might not know the full context.

By the time The Big Con published in 1940 the subcultures Maurer described and chronicle were already fading into sepia-tinged nostalgia. And yet, the book landed him in some trouble, for one of the glossary terms —“Winchell” as slang for a mark—stoked the ire of the man whose name was co-opted. Walter Winchell, learning about it from Harry Hansen’s book column, first wondered if the slang term was “German propaganda.” He was still upset about it as late as 1949, upon The Big Con‘s paperback release, pointing out an error about royal flushes and aces that reads more as petty carping than an actual correction. Apparently, sometime in between, Winchell unsuccessfully sued Maurer for defamation.

1941 photo of Maurer and academic with ape (Courier-Journal)

1941 photo of Maurer and academic with ape (Courier-Journal)

Winchell’s ire aside, reviews for The Big Con tended to be good, praising the book as “instructive” or “well-written.” Its success was more in influence than in pure sales; the argot Maurer chronicled seeped into larger culture, directly or indirectly, through novels like Nightmare Alley by William Lindsay Gresham, musicals like Meredith Willson’s The Music Man (1957), and films like Nobody Lives Forever (1946).

Maurer, meanwhile, had other subcultures to investigate. He chronicled the speech patterns of pickpockets, dope addicts, hustlers and more in hundreds of articles for academic journals (like American Speech) or general-interest publications (like The New Republic or the Saturday Evening Post). Many of these columns were collected and revised in book form, from Narcotics and Narcotic Addiction (1954, with Victor Vogel) to Kentucky Moonshine (1955, with Quinn Pearl) to Whiz Mob: A Correlation of the Technical Argot of Pickpockets with Their Behavior Pattern (1964).

Maurer’s help editing the Dictionary of American Slang, originated by H.L. Mencken, also furthered his reputation (his colleague Raven McDavid served as editor), as did spending a year in Germany teaching linguistics on a Fulbright fellowship. He also dabbled as a book critic, usually for the Courier-Journal, beginning not long after The Big Con was released. Maurer largely reviewed nonfiction, but a Virginia Woolf short story collection attracted his praise, as did—by coincidence or symmetry—an early novel by Vladimir Nabokov. Maurer praised King, Queen, Knave for its “literary magic” and commended Nabokov for “a gripping story which is, at the same time, a parody not only on all novels of this genre, but on itself and the author as well. And this takes some doing.”

And whenever a reporter needed an expert on argot and specific mindsets, Maurer was there with a pithy quote. Speaking as part of a panel on criminal subcultures and behavior on Studs Terkel’s radio program in 1967, Maurer threw out an observation that rings startlingly true today: “many professional criminals have lots of the characteristics that that make for success in the dominant culture if they’re channeled into certain areas. In other words, if they’re kept barely on the inside of the law, it’s crossing over that that boundary line that gets them in.”

Even Maurer himself wasn’t immune from the crossing of boundary lines, as he discovered a few years later.

***

In early 1974, David Maurer got a telephone call from S.J. Perelman, the noted humorist and New Yorker writer. Perelman had just come back from a screening of The Sting, the Oscar-winning film featuring Robert Redford and Paul Newman. After watching the entire film, Perelman turned to his seatmate, the New Yorker illustrator Al Hirschfeld, and said, “Maurer’s been ripped off.”

Maurer wouldn’t have known otherwise. He hadn’t seen The Sting because he didn’t go to movies anymore. A few years ago, a car wreck nearly killed him and worsened his eyesight, the glaucoma now so bad that he needed Barbara and assistants like Al Futrell to help out with basic tasks. Maurer had finally retired from the University of Louisville in 1971 not only because he turned sixty-five and was eligible for Social Security, but it was too physically difficult to teach anymore. There were projects left to complete, too, such as a more academic update to The Big Con (eventually published as The American Confidence Man) and a new edition of Kentucky Moonshine.

Perelman’s indignant insistence that The Sting stole from The Big Con and that Maurer should sue the filmmakers was infectious, though. In the spring of that year, Maurer filed a $10 million copyright infringement lawsuit against Universal, the film’s producers, as well as the screenwriter, David Ward, for hewing more than a little too close to The Big Con without giving credit—or paying him any money.

Maurer, based on the news reports of the time, seemed to have a strong case. Lois Stewart, a longtime employee of the original publisher of The Big Con, told the Courier-Journal that The Sting “had the same names and the same plot as Maurer’s book. There’s no doubt about that. I gave permission for the use of a few terms in the book but not to copy the entire story.” Maurer himself told the paper: “all you have to do is read my book and decide for yourself. It’s pretty obvious.”

The following year, the case was set for trial with Judge Charles Allen of the Kentucky District Court in Louisville presiding. A screening of The Sting was scheduled to happen in open court. But the trial never happened. In October 1976, Maurer and Ward settled for a sum neither party disclosed, but which the Los Angeles Times later learned was in the vicinity of $600,000, with Maurer taking home half that amount after attorney fees and expenses. (Ward continued to deny pilfering from The Big Con, but his wunderkind original screenplay writing days ceased.)

Maurer, however, only had a few years to savor this mixed vindication and monetary reward. His health continued to worsen. He relied ever more on his assistants, working with high-intensity light, to get the most basic of tasks done. And he knew, if he confessed his darkest thoughts to Barbara, she would do, as Futrell told me, “everything to keep him alive.”

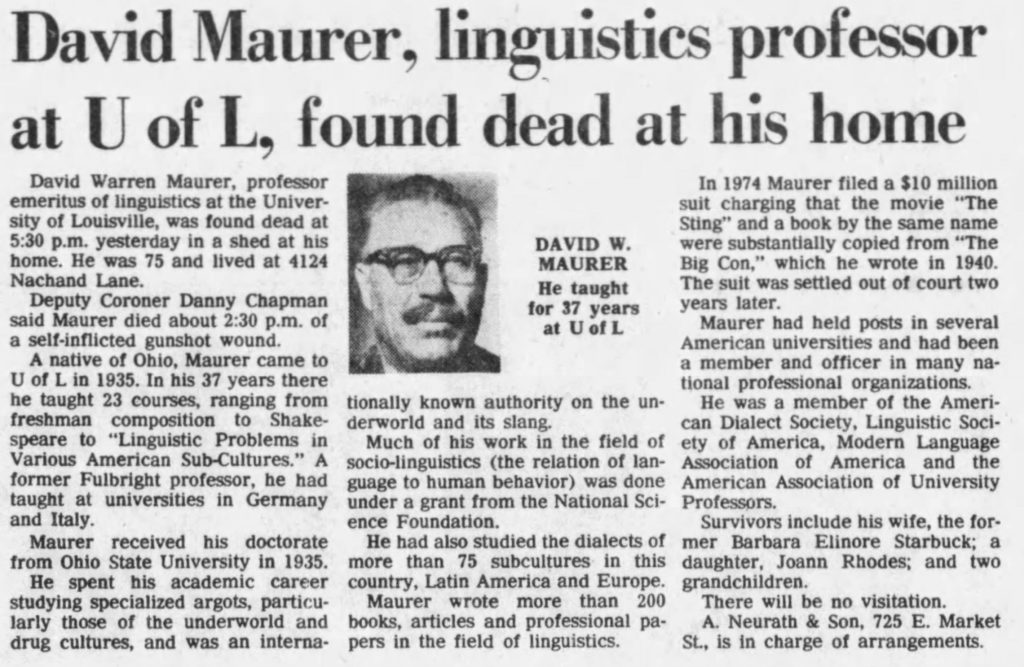

When Maurer’s body was discovered in his shed at 5:30 PM on June 11, 1981, few were surprised that the cause of death was a self-inflicted gunshot wound.When Maurer’s body was discovered in his shed at 5:30 PM on June 11, 1981, few were surprised that the cause of death was a self-inflicted gunshot wound. “It wasn’t a spur of the moment thing,” Futrell told me. “He had thought about for a long period of time. He left behind various notes at various dates. I remember being so upset. I was as close to him as anyone. I felt so bad and stupid. I was talking to Joann afterwards, and she said: “Al, do you think you could have stopped him?” I told her, “Probably not.”

Six or so months before his suicide, Maurer began to destroy confidential files, including the vast majority of interview transcripts with the criminals and con artists he had interviewed for his work. (He let Futrell keep a small sample, which was duly donated to the University of Louisville Library.) “I didn’t realize the seriousness of it,” said Futrell. “Once he died I started thinking about the things he told [me.] He was always afraid that [Barbara] would use all his resources to keep him alive. He was afraid that he was going to have some massive stroke or heart attack and not die. So that was his solution. He actually had thought of this for many many months.”

(Maurer obituary, Courier-Journal)

(Maurer obituary, Courier-Journal)

The Winter 1982 issue of American Speech was entirely devoted to Maurer. The many tributes and essays included a memoir by his colleague, Raven McDavid, who began: “Dave Maurer was a person about whom legends accumulated, whether he wanted them to or not.” On the one hand, Maurer wanted his work to take precedence over his life. On the other hand, the work itself, tied as it was to the lives and work of professional criminals, has a glamour, even a sexiness, that few other ethnographic pursuits possess.

As Luc Sante wrote in his introduction to the 1999 reissue of The Big Con, such criminals have “fully emerged from the underworld and entered the mainstream, where he may be far less colorful and imaginative, but no less on the grift.”What David W. Maurer thought had ended in the 1930s has returned with apparently bottomless vengeance, which makes The Big Con required reading not only for its glimpse of past misdeeds, but as a guide to the timelessness of criminal behavior. The games may have changed, but a sucker is forever.

__________________________________

A Glossary of Essential Maurer Slang

__________________________________