People think they have the lowdown on the down-low life of mid-century American writer Cornell George Hopley Woolrich (1903-1968)—author, primarily during the Thirties and Forties, of over a dozen crime novels, including his celebrated series of “Black” mysteries (The Bride Wore Black, The Black Curtain, Black Alibi, The Black Angel, The Black Path of Fear and Rendezvous in Black) and more than two hundred pieces of short crime fiction, including such classic tales as “After Dinner Story,” “The Night Reveals,” “Three O’Clock,” “Momentum,” “Marihuana,” “Guillotine,” “Post Mortem,” “Murder, Obliquely” “The Living Lie Down with the Dead” and “Speak to Me of Death.” Cornell Woolrich’s biographer, Francis M. Nevins, who has hugely influenced modern-day perceptions of the crime writer, pronounced dramatically in his Edgar Award winning 1988 Woolrich biography, Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die, that his tortured subject suffered “the most wretched life of any American writer since [Edgar Allan] Poe”—and I recall that a blogger since then has quipped that surely even the melancholy Poe had more fun. It is my contention, however, that some of what has been accepted as fact in Cornell Woolrich’s grim life story, like certain salacious details concerning his sexuality and his short-lived marriage, are part of what might be termed the author’s “black legend”—a tale as dark as his darkest fictions but filled, like the human heart, with falsity. Fake “facts”—possible bunkum, if you will—have proliferated about Cornell Woolrich over the last half-century, crushing under their cruel weight more nuanced and sympathetic takes on a complex man, who in spite of his manifold flaws was arguably more sinned against than sinning.

Herewith are some of the sharpest of the black legend’s shards, painfully fashioned over the last half-century from Francis Nevins’ mold, beginning with the master craftsman himself. Witness how the legend grows over time:

(1) While in Hollywood, Woolrich fell in love with and married a producer’s daughter who left him after a few weeks and later had the marriage annulled. Woolrich returned to New York and his mother….[He] spent most of his life in an intense, almost pathological, love-hate relationship with her….a diabetic and an alcoholic, he was obsessed with the fear that he was homosexual [and he] lost touch with most of the few acquaintances he had ever had.—Francis M. Nevins, introduction to Nightwebs, a collection of Cornell Woolrich short fiction (1971)

(2) Woolrich’s own life was a mess, dominated by his life-long, near-pathological love-hate relationship with his mother. His one stab at happiness resulted in a marriage that only lasted a few weeks, then was annulled. He ended as a diabetic and alcoholic, friendless, obsessed with the fear that he was a homosexual….”Bobby Mather on Books,” syndicated newspaper review of Nightwebs (1971)

(3) In December of 1930 [Woolrich] entered a brief and inexplicable marriage with a producer’s daughter—inexplicable because for several years he had been homosexual. He continued his secret life after the marriage, prowling the waterfront at night in search of partners, and after the inevitable breakup Woolrich fled back to Manhattan and his mother.—Francis M. Nevins, Introduction to Ballantine paperback reissue of Woolrich’s The Black Curtain (1982)

(4) Clearly his homosexual life was of the most furtive and sordid variety, a side of himself that he despised and was ashamed of, that he could neither accept nor suppress….Why did he propose to Gloria in the first place? Two possible reasons suggest themselves: as a sick joke, or to provide cover for his secret life….Perhaps a third reason he married Gloria was that he couldn’t live without a mother.—Francis M. Nevins, First You Dream, Then You Die (1988)

(5) According to Nevins, Woolrich was a thoroughly self-contemptuous homosexual, who liked dressing up in a sailor suit.—Michael Dirda, “The Author Wore Black,” Washington Post review of Francis M. Nevins’ First You Dream, Then You Die (1988)

(6) Woolrich was in fact gay and miserable and seems to have kept the closet of concealment pitch dark. During his short marriage his wife pried open a suitcase and found a diary in which Woolrich recounted his sexual adventures, cruising the waterfront in a sailor uniform at night.—Charles Champlin, “Poet of the Century’s Shadows,” LA Times review of Francis M. Nevins’ First You Dream, Then You Die (1988)

(7) He hated himself because he was small, puny and weak. He hated his homosexuality and the fact that he had never consummated his one and only marriage. He had the most wretched life of anyone contributing to American literature since Edgar Allen Poe.—Francis M. Nevins, interview with John Stanley in San Francisco Chronicle (1991)

(8) In December 1930….Woolrich hastily married twenty-year-old Gloria Blackton….The marriage was never consummated. A graphic diary that Gloria eventually found and read but later returned to Woolrich (who destroyed it) indicates that he had been homosexual for some time prior to the marriage, which he had entered as a sort of sick joke, or perhaps for cover. In the middle of the night he would put on a sailor outfit he kept in a locked suitcase and prowl the waterfront for partners. The marriage soon ended and Woolrich fled to New York and his mother.—Francis M. Nevins, “One Hundred Years of Loneliness,” The Believer (2003)

(9) [Woolrich] apparently never achieved a satisfactory romantic relationship and during his sham marriage he would don a sailor suit in the small hours and look for partners on the Los Angeles waterfront.—Jon Breen, “Dark Deeds,” The Weekly Standard (2005)

(10) Woolrich was perhaps the most deeply closeted, self-hating homosexual male author that ever lived.—Francis M. Nevins, “First You Read, Then You Write,” Mystery*File (2010)

(11) By all accounts, Cornell Woolrich was a real son of a bitch. A self-hating gay man who once married a naive young woman as a cruel joke, refused to sleep with her and then left her a written account of his escapades with other men, he lived most of his life with an overbearing mother who said she would die if he ever left her. When she finally did die years later, Woolrich drank himself into a decade-long stupor, developed gangrene and died weighing 89 pounds. It was a miserable end to a thoroughly rotten life.—Jake Hinkson, review of the film Fear in the Night (adapted from Woolrich’s “And So the Death”/“Nightmare”), The Night Editor (2010)

(12) Woolrich was himself, alas, pretty much a miserable son of a bitch….A self-hating gay man who tormented a young wife for a short time before retreating to a booze-soaked codependency with his beloved/despised mother…Woolrich was as unpleasant as many of his darkest scenarios….He channeled that vision not only into a life of debauchery and cruelty but also into his fiction….—Jake Hinkson, “Pulp Kafka: The Nightmares of Cornell Woolrich,” Criminal Element (2011)

(13) [Woolrich] was a creep—not because he was gay, but because of the diary, and because he left it behind for Gloria to read. Then there’s the fact he lived with his mother until he was 53, when she died. By itself that would just be kind of odd; taken with everything else it tends to red-line the creep factor. (It sounds like Sebastian and Violet Venable in Suddenly, Last Summer.)—Jim Lane, “Lost & Found: Night Has a Thousand Eyes,” Jim Lane’s Cinemadrome (2011)

(14) There’s just so much dark and coded queerness in Cornell’s writing. He lived with his mother and kept a cruising sailor suit folded up neatly under the bed for use.—Guy Maddin on the film The Chase (adapted from Woolrich’s The Black Path of Fear) in The Best Movie You’ve Never Seen (2013)

(15) Like the middle-aged Woolrich, as described in biographies, Jeffries…is a heavy drinker and a closeted homosexual with a mother fixation and a short, disastrous marriage behind him. New York Times review of the play Rear Window, adapted from Woolrich’s “It Had to Be Murder” (2015)

(16) Woolrich was a compulsive liar, always rewriting facts to tell a better story. We do know, thanks to Nevins’ research, that Woolrich was a self-loathing gay man whose lifelong residency in a locked closet no doubt contributed to the secrecy and paranoia which drips from his stories.—Eddie Muller, introduction to Woolrich’s The Bride Wore Black (2021)

Was Cornell Woolrich the hateful and self-hating gay man described above, or over the decades has Woolrich’s black legend simply grown taller and meaner in the telling? Let us take a closer look at what we really know about the strange individual who was arguably twentieth-century crime fiction’s most eloquent chronicler of death and despair.

As the note on the Cornell Woolrich papers held at Columbia University states, there is, in fact, “very little information” about the author’s personal life, given his immense stature in the history of crime writing. We know that his parents were Jorge Rodolfo Genaro Hopley Woolrich, a bookkeeper and civil and mining engineer of Anglo-Canadian and Mexican descent originally from the Mexican state of Oaxaca, and Claire Attalie Tarler, the eldest child of George Abraham Tarler (formerly Gyorgi Avraam), a wealthy American immigrant importer/exporter born in Odessa, Russia in 1848, who migrated first to England and thence to the United States in 1869, becoming a naturalized citizen seven years later; that his parents parted ways a few years after their 1903 marriage, leaving young Cornell to live a lonely, peripatetic life in Mexico for a time with his father; that in 1917 he returned as a teenager with his mother to his maternal grandfather’s house in New York, never seeing (or perhaps even hearing from) his father again; that he attended Columbia University in the Twenties but dropped out before he received his degree, publishing in 1926 his first book, Cover Charge, a Jazz Age novel inspired by F. Scott Fitzgerald, at the age of twenty-two (the author claimed he was nineteen); that he was briefly and unhappily married to a young woman in California, where he had moved in 1927 to work as a screenwriter after his second novel, Children of the Ritz, won a $10,000 prize and was optioned by a Hollywood film studio; that after the collapse of his marriage in the winter of 1930-31 he moved back to New York and commencing in 1933 lived for nearly a quarter century with his mother, until her death in 1957; that afterward he resided increasingly reclusively until his own demise-by-degrees in 1968. Surely in the last decades of his life Woolrich was, whatever else one may think of the man, many lonesome miles away from Tennessee Williams’ handsome, globetrotting gay sophisticate Sebastian Venable in the play and film Suddenly Last Summer (although Sebastian’s grim death certainly has its Cornellian aspect).

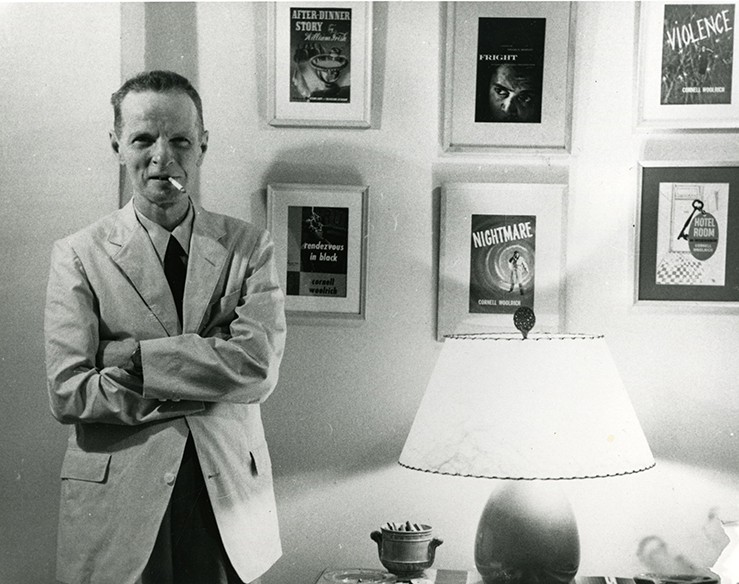

Ironically there is comparatively little personal detail about Cornell Woolrich in Francis Nevins’ evocatively-titled biography of the author, First You Dream, Then You Die (the title comes from Woolrich), especially given the mammoth size of the book (613 pages of smallish type, including a microscopically printed index). Most of Dream—a classic doorstop book if ever there were one—is given over to minute detail on almost every piece of fiction Woolrich ever wrote, as well as the numerous film, radio and television adaptations that have been made from his work, with the result that what information is provided on Woolrich’s life is dully buried in the dead weight of bibliographical data and plot summaries. Much of Nevins’ influence on the general public’s perception of Cornell Woolrich probably can be traced more directly to the introductions he contributed, beginning three years after the author’s death in 1968, to myriad Woolrich short fiction anthologies and novel reprints (particularly publisher Ballantine’s lauded early Eighties paperback reissues, the moody cover art for which, rendered by Larry Schwinger, recalls the haunting isolation of American painter Edward Hopper’s urban art, particularly his 1942 painting Nighthawks). Clearly Nevins labored diligently to dig up information about the enigmatic author, but there simply does not seem to be a great deal of surviving primary material out there to disinter about this desperately reclusive man, who by his own declaration was born to live a solitary life. (My contributions to the “dig,” drawn mainly from research in newspapers and public records, are scattered below.)

A rather similar case in some ways is that of solitary hard-boiled crime writer Raymond Chandler, where almost all the personal detail on the author which has fueled his three (and counting) biographies comes from the frequently acerbic and opinionated late-night letters he wrote during the last twenty years of his life. (He lived to the age of seventy.) However, these letters which Chandler wrote in the 1940s and 1950s make a tremendous difference, bringing his remarkable personality vividly alive. We have nothing like this from the hand of Cornell Woolrich. There are astonishingly few Woolrich letters quoted in Dream. For personal detail on the author we are largely dependent on his fragmentary memoir, Blues of a Lifetime, which Nevins deems unreliable (except when he relies on it), and recollections from people—some, like the noted science fiction writer Barry Malzberg, still with us—who got to know Woolrich in the 1950s and the 1960s, that sad decade when Death callously compelled the author to try to adjust to a lonely life without mother.

The personal recollections and details of Cornell Woolrich’s earlier years which Nevins offers in Dream are sparse indeed. We do not even get to see childhood or college photos of Woolrich, nor photos of his elusive father, nor of his mother and his maternal grandfather’s grand house, where he probably spent his happiest years (such as they were). Dates are vague and individuals who must have had some impact on Woolrich’s young life are mostly missing from the story. I myself have found that in 1905, less than two years after their marriage, Genaro Woolrich, an 1895 graduate of Heald’s Business College in San Francisco, was living with Claire Tarler and Cornell at Claire’s widowed father’s house at 239 West 113th Street in Morningside Heights, Manhattan. At the time he was employed not as an engineer but a bookkeeper, possibly in his father-in-law’s import/export business, although Heald’s had established a School of Engineering and Mining in 1875. Residing with them at the house were Claire’s five adult siblings: two brothers, George and Irving, and three sisters, Estelle, Lillian and Olga, all of whom were unmarried. (There was also a native Hungarian house servant.)

The Russo-Jewish background of the family is evident from the names of the Tarler siblings, as well as from their Tarler relations. Claire had as well an uncle and an aunt, a younger brother and sister of her father’s, Sigmund Tarler and Dora Tarler Silverburg, who lived with their spouses and children in Manhattan and the Bronx respectively. Dora married Moses Silverburg, a dry goods salesman, while Sigmund was employed as a physician. His son Paul Sigmund Tarler, one of Claire’s approximately ten Tarler cousins in New York, became a prominent Manhattan dentist. Confusingly Sigmund Tarler also fathered, like his brother George, daughters named Lillian and Olga.

Half-Mexican and nominally Catholic, Genaro is said to have been uncomfortable living in America with a pack of Tarler in-laws (at least one of whom, Irving, had, according to his descendants, an abusive disposition; see below). One can conjecture that there must have been a clash of cultures at the house—although on the matter of religion, George Tarler and his children appear not even to have been nominally Jewish, with Claire and Genaro having married at a ceremony in Harlem at the Episcopal Church of the Archangel (which in an ill omen burned down nine months after the wedding, not long before Cornell was born) and all of Claire’s siblings, it appears, having taken, like Claire, partners outside the Jewish faith.

While George Tarler’s deceased wife, Sarah “Sadie” Viola Cornell, was said to have come from an old, presumably Protestant, New York family (the surname Cornell, clearly much beloved by the Tarler children, is of Dutch-Anglo origin and Cornells were some of the earliest settlers of New York), Sadie herself seems weirdly shrouded in mystery, with seemingly virtually nothing being known about the Tarler matriarch except that she ostensibly died sometime in the early to mid-1890s, after having given birth to six children in seventeen years. In Dream Francis Nevins claims Sadie’s old New York family was “prominent,” but he provides no evidence to support this claim. All I have found is that a Sarah “Cornwell” is recorded as having wed George Tarler in Manhattan on April 15, 1874, about seven and a half months before Claire’s birth on November 29. It would be a crowning irony to Cornell Woolrich’s ill-starred life if his first name, of which the Tarlers obviously were inordinately proud, really should have been the more mundane “Cornwell.” I think most people would agree with me that “Cornwell Woolrich” has not quite the same ring.

Possibly there was business friction as well within the Tarler household, for the in 1904 a federal court had stiffly fined George A. Tarler the sum of $2,123.55 (about $65,000 today) for smuggling goods from Mexico through the border town of Eagle Pass, Texas, only dropping its criminal proceedings against him after Tarler forked over the hefty amount. Had his Mexican son-in-law, who later in life was known to cross over into the United States through Eagle Pass, anything to do with this smuggling operation? In the 1990s Genaro’s nephew Carlos Burlingham described his uncle to Francis Nevins as “a very good-looking man with deep blue eyes,” but then added, with a faintly sinister edge, that, like a character in a Cornell Woolrich crime story, “you would never see him to smile. He always had a very narrow smile.” He also characterized Genaro, again conveying something of a sense of menace, as “somewhat schizoid, extremely withdrawn, extremely silent” and a persistent drinker of rum.

Supposedly Genaro tersely told Claire, after but a few years spent in New York with her family: “I have to go. I don’t like this place. Your role is to follow me.” Genaro left New York for good in1907, taking his wife and son back with him to Mexico. However, Claire defiantly returned to her father’s house in Manhattan, leaving behind Cornell, who was as young as six or seven at the time, with Genaro. Not until 1917 did Claire retrieve her son, returning to Mexico a final time and then departing for New York with him aboard S. S. Monterrey in June, when Cornell was thirteen. Apparently neither mother nor son, once safely back at 239 West 113th Street, would ever again see Genaro, who remained domiciled in Mexico until his death in 1948.

Altogether it was an unsettled, and doubtlessly unsettling, existence for a pale, diminutive, unhealthy youngster, whose recorded height as a teenager in 1917 was only 4’5”. Should a boy who grew up in Mexico not have been able to achieve some semblance of a tan? Although Francis Nevins seemingly overlooks this point, it has occurred to me that Woolrich’s diminutiveness and paleness, his narrow face and sunken cheeks, upon which his acquaintances so frequently and pejoratively remarked, may have been a product of something like (1) hemolytic anemia, an abnormal breakdown of red blood cells for which extreme pallor is a symptom, and (2) failure to thrive, i.e., inadequate growth in a child, for which anemia is a cause.

Significantly, hemolytic anemia also can cause jaundice, which in his memoir Blues of a Lifetime Woolrich claims he suffered from in the mid-Twenties (probably 1925), prompting him to leave Columbia University to write his first novel, Cover Charge. The author’s uncanny paleness and thinness are evident in the few surviving photos of him as an adult, and they are confirmed over and over again by his contemporaries. The distinguished academic and public intellectual (and confirmed mystery fan) Jacques Barzun, a Columbia classmate of Woolrich’s, recalled in 1985 that physically Woolrich was “abnormally narrow in the face, almost sunken-cheeked, and terribly pale,” while another man who first met Woolrich in the mid-Twenties, editor and literary agent Harold Norling Swanson, in a 1980s letter to Francis Nevins strikingly described the aspiring author as a “boy-man” who “looked like he might have stepped out of a Charles Addams drawing. He had very dark clothes, a long black overcoat that almost hit his shoes, and he had a white face and the appearance of not having enough to eat….”

Marian Blackton Trimble, who socialized with Woolrich in Hollywood a few years later (Woolrich married her half-sister; see below), described the author to Nevins as “a very frail and pathetic-looking person, very shy, very withdrawn.” Noting his reluctance ever to be photographed, she added: “I could understand why he would not at the beach, because he did not cut a particularly heroic figure in a bathing suit. He was…a very skinny chap.” Yet another individual, crime writer Steve Fisher, saw Woolrich occasionally in the late Thirties and recalled him as “tall, skinny, redheaded [Woolrich himself claimed to be brown-haired; possibly the shade was his Uncle Irving’s reddish-brown, or auburn] and very pale.” That Fisher based his villainous cop “Ed Cornell” from his 1941 noir novel I Wake Up Screaming on Woolrich is apparent: “He had red hair and thin white skin and red eyebrows and blue eyes. He looked sick. He looked like a corpse. His clothes didn’t fit him….He was frail….He might have had T. B. He looked like he couldn’t stand up in the wind.”

Intriguingly the wasting protagonist victim in Woolrich’s 1939 horror story “Vampire’s Honeymoon,” aka “My Lips Destroy,” is diagnosed in detail with anemia—although his condition arises from, shall we say, unearthly causes. (Woolrich also devised a plot around hemophilia in another tale, “The Detective’s Dilemma.”) In Dream Nevins quotes all four of the above physical descriptions of Woolrich along with the passage from Fisher’s novel and he discusses the plot of “Vampire’s Honeymoon” (which he treats as an allegory of Genaro’s and Claire’s failed marriage), yet surprisingly he does not connect the pale dots to form a picture of a person who may well have been clinically anemic and gravely debilitated from childhood. Indicative of his apparent obtuseness on this matter, Nevins, in an interview about Woolrich which he conducted with editor Lee Wright (see part three), comments passingly, “I’m sure he [Woolrich] didn’t eat much, considering how thin he was,” to which Wright responds airily, “Well, big drinkers are very rarely big eaters.” It never seems to have occurred to either of them that Woolrich’s poor physical condition might have had some origin other than alcohol abuse.

Questions occur to me, however. Could Woolrich have had celiac disease, a chronic digestive and immune disorder which pediatricians did not link with wheat consumption until the 1940s, after the author had entered middle age? Celiac disease can result in anemia from iron deficiency. As the Austin Gastroenterology website puts it, “Anemia and celiac disease very often go hand-in-hand.” More generally, could not the sort of wretched suitcase existence which Woolrich’s estranged parents allowed him to lead during his formative years have resulted in his receiving insufficient and inadequate nutrition? Doubtlessly Claire evolved into a protective, or indeed overprotective, mother, but in so doing perhaps to some extent she was compensating for her and her wayward husband’s earlier neglectful upbringing of their son.

It seems clear enough to me that the young Cornell was neglected not only physically but emotionally. “I did a lot of traveling until I was thirteen,” Woolrich told an interviewer, with something of a plaintive note, in 1927, after he had precociously launched himself upon a career as a novelist. “Father was a civil engineer and we were always on boats and trains going from one place to another. I lived in hotels a lot and went years before meeting other boys. I associated with grown-ups. That had its effect.” The lonely boy found vicarious companionship in some of his father’s books, including “a worn old copy of [Robert Louis’ Stevenson’s] The Black Arrow” and “a dog-leafed paper[back] edition of Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame in Spanish”; and in particular “he fell in love immediately with [Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s] The Last Days of Pompeii.” Woolrich confided to his interlocutor that he had read those books and others “hungrily, dozens of times, carrying them jealously about with him in his trunk.”

Something about the impending doom betokened by an active volcano may explain the unique appeal of The Last Days of Pompeii to the young Woolrich, for early in his life, according to his later recollection, the consciousness of death had descended upon him like a cloud of ashes. In his memoir Blues of a Lifetime, Woolrich memorably avowed that he had been possessed by a “sense of personal, private doom ever since the age of eleven, when “huddling over my own knees, [I] first looked at the low hanging stars of the valley of Anahuac, and knew I would surely die finally, or something worse. I had that trapped feeling, like some sort of poor insect that you’ve put inside a downturned glass, and it tries to climb up the sides, and it can’t, and it can’t, and it can’t.” This little bit of morbidness is not the observation of a happy boy.

Even as Woolrich accompanied his father on jobs in Havana and the Bahamas and “small border towns in Arizona and on the edge of Texas,” he longed to return to the flashy New York of fable (“I wanted to come up here awfully bad.”) Yet Genaro “could not [or more likely would not] get away to show him the sights up North.” After finally making it back to New York in his mother’s charge in 1917 Woolrich declared, “I was happy just walking down Broadway and staring in at the shop windows. I thought every six months would be the last, that [father] would send for us. But from one cause and another, the visit has been prolonged into years.” The 1920 census shows that Woolrich—now sixteen and a student at DeWitt Clinton High School a year away from enrolling at Columbia University—was still residing at his grandfather’s house, which again was crowded with George A. Tarler’s children, as well as Cornell’s only Tarler cousin to that point—though in Dream Nevins, relying on Woolrich’s own highly selective memoir, asserts that only Cornell, his mother, grandfather and an unmarried aunt lived there at the time.

In Blues of a Lifetime Woolrich has more to say about the house, which the Tarlers moved into around 1895, than its inhabitants, excepting his mother and grandfather. Characteristically he concludes with a plaintive note:

It had many charming features, which were soon to disappear from such houses—along with the houses themselves, as the mass production of multiple-apartment buildings took over….it had fireplaces in most of the rooms, even the bedrooms, topped by mantels, and in several of them they were flanked by floor-to-ceiling pier-glasses. It had intricate chandeliers in the main rooms of brass or of prismatic glass, originally used for gas but later transformed for electricity. It even had oval frescoes painted on a couple of the ceilings, portraying cherubs frolicking about with overflowing cornucopias and streamers of ribbons against an azure sky….It had many such touches….But books it did not have, not in great quantity, still less of any great quality.

Residing at the dawn of the Roaring Twenties at this grand, bookless house were, in addition to Woolrich and his grandfather and mother, who still retained Genaro’s surname (it seems doubtful that she and Genaro ever divorced, although Genaro later remarried and started another family), were six additional individuals: unwed eldest son George Cornell Tarler, a lawyer and diplomat (after his father’s death in 1925 he married at age fifty and moved into a luxury Park Avenue apartment, but he fathered no children); daughter Estelle and her native Cuban husband, Emilio Manuel Garcia, a salesman with an electrical engineering firm; widowed daughter Lillian and her four-year-old son Archie Cornell MacBain (named for his late Scottish father and Lillian’s late mother); and youngest daughter Olga, a childless divorcee. (The Hungarian house servant was succeeded by a Finnish girl and later an Irish lass.) Once again young Woolrich seems to have found himself isolated among adults, as he had been in Mexico, along with a single small child.

One gets the impression that the Tarler patriarch for the most part maintained a firm hold over his offspring. A wealthy self-made man and world traveler who spoke several languages, George, mustachioed, top-hatted, black-coated and with a cigar in his right, ungloved hand, though only 5’6” stands proudly and domineeringly, like a Victorian (or in this case Edwardian) robber baron, before the camera in a 1910 photograph of him taken in Scotland. Of his six children, only Irving Cornell Tarler—the youngest of the family and a globetrotting salesman with the petroleum company Texaco—had managed to depart permanently from the ancestral demesne, having wed Elizabeth Morgan, daughter of a Pennsylvania hardware merchant the same year the 1920 census was taken. Irving and Elizabeth moved to Scarsdale and around 1930 adopted an infant son, Craig Cornell Tarler, but they divorced when Craig was around thirteen, Irving being, according to one of Craig’s children, a “controlling and emotionally abusive person.” Afterward Irving, like Genaro Woolrich, maintained “little to no contact” with his son. On a passport issued when he was twenty-six, Irving is described as 5’7” with a florid complexion, hazel eyes and auburn hair—the latter attribute of which he probably shared with his sister Claire’s boy.

Despite his close proximity to most of them in the Twenties, all of Cornell Woolrich’s Tarler relations, aside from his mother and grandfather and an anonymous aunt, go unmentioned in Francis Nevins’ biography, as they do in Woolrich’s memoir Blues of a Lifetime. It is like Woolrich wished them out of existence, in the manner of the deific six-year-old boy with omnipotent psychic powers in the famous Twilight Zone episode “It’s a Good Life.” In Blues Woolrich writes, “I was the first grandson, then the only grandson,” a patent untruth which blots out Woolrich’s younger cousins Archie Cornell McBain and Craig Cornell Tarler (born in 1915 and 1930 respectively), the former of whom actually resided at the Tarler house with Woolrich while their grandfather still lived. Moreover, when Archie, a Manhattan movie theater manager, married in 1938, Woolrich was one of the two witnesses at the ceremony. Perhaps the frugal Woolrich, an avid cinema goer and film fan throughout his life, cadged passes from his cousin.

Both Archie McBain and Craig Tarler lived into their ninth decades and passed away in the twenty-first century. His first marriage (to restaurant waitress Dorothy Marie Lynch, the daughter of a construction foreman) having failed after fewer than five years, Archie, 5’10” and 175 pounds with brown hair and brown eyes, married twenty-year-old Marie Plunkett in New Jersey in 1943, served in the navy for the duration of the war and expired in 2005 at the town of East Farmingdale on Long Island at the age of eighty-nine. His widow Marie died just three-and-a-half years ago, at the age of ninety-five. Presumably both Archie MacBain and Craig Tarler would have been available for interviews about their famous cousin Cornell during the 1970s and 1980s, when Nevins was compiling Woolrich’s biography—a sadly lost opportunity (particularly in the case of Archie, who must have known Cornell well in the Twenties and Thirties) to get another side of the crime writer’s sketchy story.

However, an early—and to me incisive—recollection about Woolrich, partially included in Dream, comes from a 1985 interview by German filmmaker Christian Bauer with Jacques Barzun, a former classmate of Woolrich’s at Columbia University, where Woolrich enrolled as a freshman in the fall of 1921 and remained through the spring of 1926. In his entry on Woolrich in the 1971 edition of his book A Catalogue of Crime, Barzun had noted that this “amiable and prolific writer” for two years had been a “classmate and friend” of his at Columbia University, where the two had “shared English classes.” To Christian Bauer, however, he presented a portrait of the author as a rather more complex young man. He recalled that in a class they both were taking—possibly John Erskine’s advanced prose course—he and Woolrich “happened to sit side by side and, as the custom was, one spoke to one’s classmate without any particular introduction or any particular purpose. I found Cornell very shy indeed, very retiring, very suspicious. But somehow…he and I got into more and more conversations. As far as I could see, I was the only person in either of those classes with whom he had any sort of human dealings. He always rushed out of the class without lingering with any other students.”

Sometimes Barzun’s quirky classmate would suddenly break off their conversations with words to this effect: I’ve got to go now. I’ve got to see Mother. Barzun allowed that while Woolrich in actuality did, in spite of his reputation as an incurably morose individual, have a “sense of humor,” it consisted predominantly of

a sense of the grotesque, the ironic. He was a rather bitter young man. He made sarcastic comments very easily…about life in general, about other people, about institutions, about the older generation…..He had a sense of destiny, both on the positive side, that he was going to accomplish something, and on the negative side, that he couldn’t possibly do it, that something would interfere, the ceiling would fall in on him just as a contract was being signed for the next book, or something of the sort.

It was the Doom of Anahuac again. In a portion of the interview which I did not find mentioned anywhere in Nevins’ biography, Christian Bauer asked Jacques Barzun whether he would be surprised to find out that Cornell Woolrich was “homosexual” and Barzun said, yes, he would be surprised. However, he added that he would not be surprised to find out that Woolrich was “asexual.” The accepted view that Woolrich was gay—or, to be more precise, a “self-hating gay”—and that this feeling of loathing, masochistically directed against himself, was the motivational force behind the author’s anguished crime writing comes, as we shall see, from the darker pages of Francis Nevins’ Dream, which marshals as its evidence for this assertion dubious hearsay recollections from a pair of elderly women, concerning events from very long ago.

*******

With the publication of his first two novels, Cover Charge and Children of the Ritz, Cornell Woolrich attained no small of measure of success as a precocious Jazz Age writer in the mold of his literary idol, F. Scott Fitzgerald. In 1927 he dropped out of college for good and, like many another syncopated dreamer, moved out west to Dreamland, aka Hollywood, where a film was being made from his second novel. Already by August a newspaper story referred to the promising young author as a “California boy.” Children of the Ritz had netted him the life-changing sum of $10, 000 (about $150,000 today) as the winner in a contest jointly sponsored by College Humor and First National Pictures, along with golden praise from the New York Times for his “fresh and lively talents” and “knack for spinning a story.”

As he worked on scripts in Hollywood, Woolrich also churned out bright tales of romance in slick magazines as well as another booze-soaked New York novel (Times Square, 1929), consciously crafting what Francis Nevins termed a “public image…of a knowing young devotee of the Jazz Age with all its works and pomps.” With “Girls, We’re Wise to You,” a 1928 article in The Smart Set, the newly-minted “California boy” flustered flappers when he chastised them for their freshness and forwardness. “Someday I’d like to meet a girl who doesn’t start calling me by my first name five minutes after we’ve been introduced, who doesn’t flirt over my shoulder the minute we get on a dance floor, who doesn’t souse gin in a taxi and get it all over my shoulders,” he lamented. “Someday I may meet a girl like that but if I do I think the shock will kill me.” The Smart Set received “hundreds of blistering letters in reply,” reports Nevins, all grist to the publicity mill.

After more than two years had passed in Hollywood–during which time he may have written, under his later popular pseudonym “William Irish,” titles and dialogue for the silent movies The Haunted House and Seven Footprints to Satan and the early talkie House of Horror (fright films all)—the day arrived when Woolrich appeared finally to have found “a girl like that.” He survived the shock of his discovery of this girl, twenty-year-old Violet Virginia Blackton, although subsequent shocks from her proved much harder for him to bear. Two days after his twenty-seventh birthday, on December 6, 1930, Woolrich eloped with Violet, the younger daughter of pioneering Hollywood filmmaker James Stuart Blackton, a yachting enthusiast frequently referred to in the press as “Commodore” who had recently lost his fortune in the aftermath of the 1929 stock market crash as well as his wife, Paula, Violet’s mother, who had died from cancer. Confusingly, Violet’s stage name as an adult was Gloria, but for a reason never made clear she was known familiarly as “Bill”—the name which I use henceforward.

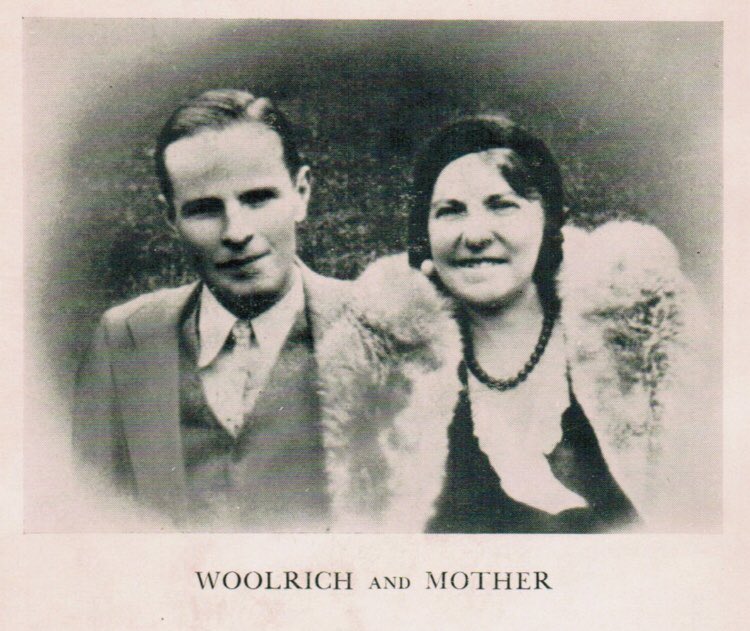

As a child Bill, then credited as Virginia Blackton, had parts in several of her father’s films, including The Virgin Queen, where improbably at the age of twelve she played the film’s lead ingénue role (a lady-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth), yet when she married Woolrich in 1930 she had not appeared in any picture over the last seven years. In 1927 Bill graduated from the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in Los Angeles, but since then her sole creative outlet, according to Nevins, had consisted of writing “a few romantic tales which were apparently published in love pulps.” He deems Bill’s appearance at the time she married Woolrich “to have been attractive if a bit plump.” In their sole known photograph together, which ran in newspapers at the time of their elopement, plump Bill Blackton and puny Cornell Woolrich admittedly make rather a queer-looking couple, a fact which soon must have manifested itself to the mismatched newlyweds.

Tellingly in Blues of a Lifetime Woolrich writes ruefully of having fallen unhappily in love with a trio of women, the last of whom was Bill Blackton, although he refrains from naming her: “I never loved women much, I guess. Only three times, that I’m fully aware of. And each time I got more or less of a kick in the jaw, so there wasn’t much incentive to go ahead trying more frequently….The third time I married [the woman], and it was only after it happened that I realized I wished I hadn’t.” Cornell was third time unlucky, in short. But just what went wrong between the two lovebirds?

Was the author’s motivation for marrying Bill Blackton really love (or imagined love), as he claims, or was it something altogether more calculating and sinister? Based on a 1977 interview which he conducted with the deceased Bill’s seventy-six-year-old half-sister, Marian Constance Blackton Trimble, Francis Nevins darkly speculated in Dream about Woolrich’s black motivations in wedding his bride, asserting variously (and somewhat feverishly) that the author was (1) making a “sick joke” at his bride’s expense (2) looking for “cover” for a covert though highly promiscuous gay life (Bill was Cornell’s beard, in other words) or (3) looking for a new mother figure, having left Claire far behind him in New York when he moved out to Hollywood.

Yet as we have seen Woolrich presents himself as someone who sincerely wanted to make a real go of marriage, having been “in love” with his bride. Perhaps this reflected a desire on his part to alleviate loneliness afflicting him at the age of twenty-seven, rather like his tragically ill-starred, fatally self-deluded character Louis Durand in his 1947 William Irish crime novel Waltz into Darkness. In the case of Louis Durand, a decade older than the author when he married Bill, loneliness finally reached a crisis point where “[a]ny love, from anywhere, on any terms” would do, just as long as he would not “be alone any longer.” However, Woolrich also admitted in his memoir that, when he was young, he found, after spending a short period of intimacy with another person, that he often desired aloneness again:

For if anyone ever entered my life for more than a few days or weeks at a time, the doors would remorselessly swing together and shut them out again, just as though they worked on spring hinges. And then inevitably, the next following New Year’s Eve, I’d resurrect them in memory and toast them and mourn their passing. I cherished my solitude; I liked to have something to lament. And more pertinently, it made a wonderful background for my work. I sat well on me while I was young. Then when I no longer was quite so young, it sat less well….

Nearly a half-century after the event, Bill’s sister Marian Trimble contrastingly provided Nevins with a detailed—and quite dark—account of Bill’s and Cornell’s terrible marital misadventure, one in which Woolrich was memorably cast in the role of the deepest-dyed of villains. In Dream Nevins states that Trimble told him that Bill told her that

(1) She and Woolrich never consummated the marriage. (“….suddenly [Bill] flung herself on the couch and burst into tears and said: ‘He’s gone. Cornell’s gone.’ And she began to tell me that things had been very bad then, she was…a virgin….)

(2) Woolrich had homosexual encounters before and during the marriage. (“But what hurt [Bill], I think, more than anything else was the great mistake he made in leaving a diary….It covered the period from the time when he came to Hollywood until just before he left…he also spoke in this diary of how it might be a really good joke to marry this Gloria Blackton. I think that bit into her more than anything he wrote….she overlooked the grosser part of the diary.”)

Frustratingly Nevins breaks off the block quotation of Trimble at this point, writing: “The bulk of the diary, Marian told me, recounted a large number of homosexual encounters, ‘in sordid and dreadful detail.’” Then Nevins goes back again to a block quotation from Trimble telling the now infamous tale of Woolrich and his sailor suit. The author had a mysterious locked suitcase, according to this story, which one day he carelessly left open, prompting Bill to take a peek at its contents. As in the case of Pandora, the wages of Bill’s curiosity was awful indeed. “[S]he could see there was a sailor suit in it,” Trimble divulged, adding shockingly: “And he would don the sailor suit, get up in the night and leave her. In the dark he would put on the sailor suit and go down to the waterfront and find whatever experience he was looking for.”

This is a dramatic story, to be sure, but, absent the evidence of Woolrich’s putative sex diary, it remains forever hearsay, some of it (when we have to rely on Nevins’ word alone for what Trimble said to him) hearsay twice over. Allegedly Bill kindly sent the diary back to a desperately importunate Woolrich, but Nevins allows that “[n]o trace of such a diary remains among Woolrich’s papers.” Interestingly, Trimble’s other half-sibling, Bill’s brother Charles, apparently did not corroborate any of the sex shenanigans story in his 1987 interview with Nevins, who promptly dismisses him as “then seventeen years old and preoccupied with high school athletics” However, according to Nevins, Charles did confide to him that he met Woolrich a few times and thought he was a “jerk.”

Despite these qualifications, Nevins writes in First You Dream, Then You Die as if the ambiguous matter of Woolrich’s sexuality had been definitively established. Already as far back as 1971, six years before he had interviewed Marian Trimble, Nevins had claimed, in his introduction to the seminal Cornell Woolrich short fiction collection Nightwebs, that the crime writer in later life became “obsessed with the fear that he was homosexual.” On what basis Nevins made this claim is unclear to me, yet when he published Dream seventeen years later, he went even further with this line of thought. No longer had Woolrich obsessively feared he might be gay; now he had avidly, if furtively, pursued same-sex encounters of the most degraded sort:

Clearly [Woolrich’s] homosexual life was of the most furtive and sordid variety, a side of himself that he despised and was ashamed of, that he could neither accept nor suppress, that he never acknowledged publicly and dropped down the memory hole even in Blues of a Lifetime, which he claimed to have written for himself alone. How many of the young women he mentions in his autobiography were really young men?

How many, indeed? Of course this must remain a rhetorical question on Nevins’ part, because there can be no answer to it, unless the phantom diary materializes someday. But what sort of self-despising gay man records his homosexual sex acts “in sordid and dreadful detail” in a diary—and then proceeds to leave this incendiary document behind him when he walks out on his wife? This sounds much more like a proud-and-self-proclaiming or a not-giving-a-damn gay man. While the whole episode, as described, seems bizarre in the extreme, Nevins’ view over the years has been generally accepted, and even embellished upon, as seen at the beginning of this article, by the public. Once word of the sex diary and the sailor suit got around, Cornell’s black legend was launched upon the midnight at full sail.

Nevins himself repeatedly urges upon us as fact Woolrich’s “homosexual self-loathing” throughout the many, many pages of Dream, where his assessment of the author’s character, particularly in relation to the Blackton clan, is quite harsh, even contemptuous. For example, he states in passing that “the likelihood that any of these pulps’ editors would want to buy a mystery from a pale, puny, homosexual recluse who wanted to be the next F. Scott Fitzgerald hovered close to the zero mark.” Yet the sheer unlikelihood of the “pale, puny” Woolrich donning a sailor suit and “prowling” the L.A. waterfront in search of wild gay sexual encounters never seems to occur to Nevins. Perhaps during his jaunts Cornell encountered J. Edgar Hoover in feminine drag! One would think we were talking not about Woolrich, but rather French author Jean Genet, who is known to have lived dangerously, having had the capacity and fortitude for it.

Woolrich’s 1942 draft registration card records that he was 5’9” and 122 pounds, making him not so much undersized, if the height is correct, as underweight. (According to the BMI index, 125 is the lowest “normal” weight for that height.) Evidently Woolrich never served in the armed forces during World War Two, despite being eligible at the age of thirty-eight, presumably due to physical health grounds; and instead he spent the war years at home with mother, industriously putting nightmares down on paper. Ironically in 1943 the books column in The Bainbridge Mainsheet, the newspaper of the Bainbridge, Maryland naval training center, pronounced that there were “enough new murder mysteries to curdle the blood of every sailor from here to San Diego” and advised: “If you like to read yourself to sleep don’t try…The Black Angel, a Crime Club selection, by Cornell Woolrich.” Clearly Cornell did not require a sailor suit to keep seamen up at night.

Concerning the breakup with Bill Blackton, Nevins takes the bride’s part, portraying her as the noble victim of Woolrich’s craven gay chicanery. As quoted by Nevins, Marian Trimble seems to claim that Woolrich left Bill after three weeks, just after Christmas (though elsewhere Nevins says three months), and that the smitten Bill was utterly devastated by Woolrich’s callous betrayal. “It was a blow to her that there wasn’t anything to the marriage in the physical sense, but [more so] that he had left her, because she felt this great warm and loving feeling for him,” Trimble avowed. “She was still in love with him and she was heartbroken.”

It all sounds like a melancholy scenario from one of Bill’s pulp love stories, and Francis Nevins for his part was swayed by Trimble’s tragic account of her half-sister’s Cornell-induced misery. According to Commodore Blackton’s 2016 biographer, Donald Dewey, however, the resilient Bill soon rebounded, dashing “into the arms of a carnival hypnotist who used her as a shill for a stage act.” Comments Dewey drily: “She took as long to get over the breakup at the marriage lasted.” At the height of her latest romantic fling, Bill, who was residing as “Miss Gloria Blackton” at 7656 Fountain Avenue in West Hollywood, announced excitedly to her bemused parent and siblings that her new man was going to place her “in a trance and bury her six feet underground.” Perhaps at this point Cornell started to look better to the family. After all, not wanting to have sex with Bill surely was less egregious than desiring to entomb her.

After killjoy local police nixed her boyfriend’s bizarre publicity stunt, Bill fatefully decided to take what remained of her late mother’s trust fund money (her father being on his uppers at the time), which had become available to her on her twenty-first birthday in June 1931, and with it attempt to launch an acting career in New York. There was as well an overdue legal reckoning to be had with her unsatisfactory husband. As Woolrich’s fearful amnesiac character in his novel The Black Curtain thinks, when he finds that he is being followed by someone from his past: “This was no halfhearted pursuit, no casual badgering. This was a manhunt in every sense of the word.” Bill was on a collision course with Woolrich; and in a meeting between Bill’s buoyant force and Cornell’s abject object, the author never stood a chance.

In 1932 Bill moved from West Hollywood to Manhattan, settling in at an apartment at 140 West 69th Street, two and a half miles away from the old Tarler house, where Cornell’s mother apparently still resided, seven years after her father’s death, with her widowed sister Lillian and possibly Lillian’s son Archie. (Cornell at this time lived in his own apartment, where he was trying to complete another mainstream novel.) The next year Bill filed suit to annul her marriage, contending that it had never been consummated. Francis Nevins speculates that the “imminent exposure of [Woolrich’s] homosexuality” which Bill’s suit portended “must have kept [the author] as keyed up and quivering with terror as the most hard-pressed characters in his later suspense fiction.” However as Nevins tells it the author had no reason to fear. Bill being “a decent person,” she said “nothing about the diary or the true ground for the action, which Woolrich understandably did not contest. Interviewed for the lengthy article in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, she spared him once again. ‘We should not have married,’ was all she said. ‘The whole thing was silly.’”

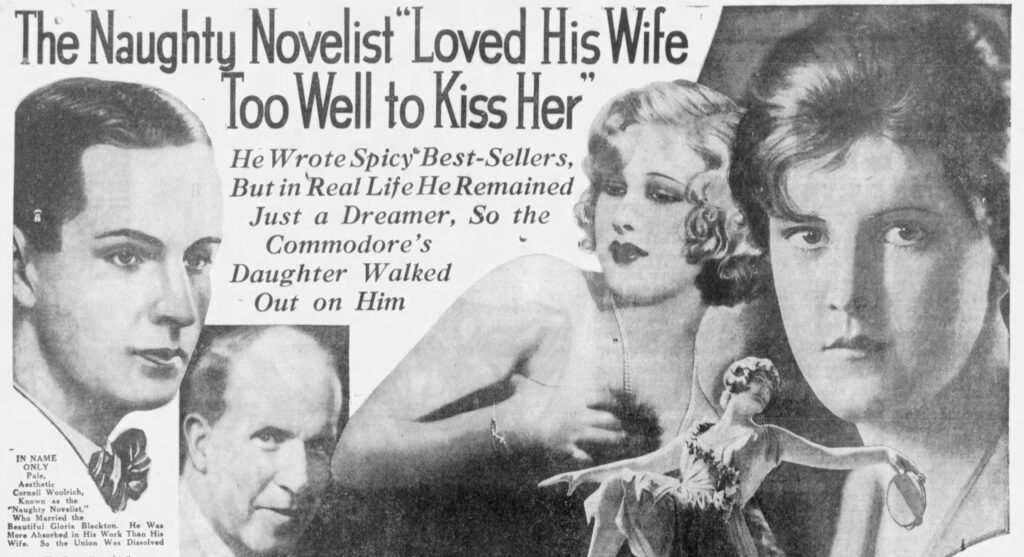

In truth Bill, not quite the beatific angel of mercy envisioned by Nevins, said rather more to the press than he credits her with saying. Indeed, the Cleveland Plain Dealer story—which actually appeared not just in the Plain Dealer but in Sunday newspaper magazine supplements all across the country in July 1933—surely was nothing short of humiliating for Woolrich. “The Naughty Novelist ‘Loved His Wife Too Well to Kiss Her: He Wrote Spicy Bestsellers, But in Real Life He Remained Just a Dreamer, So the Commodore’s Daughter Walked out on Him,” ran the embarrassing headline. Under a picture of Woolrich ran the caption “IN NAME ONLY: Pale, Aesthetic Cornell Woolrich, Known as the ‘Naughty Novelist,” Who Married the Beautiful Gloria Blackton.”

There followed additional demeaning adjectives, all of them conveying the impression that Woolrich–in contrast with F. Scott Fitzgerald, who assuredly had experienced the raucous stuff of which he wrote–was an unmanly, pathetic sissy, a mere passive and eunuch-like observer of life. Throughout the article Woolrich was damningly described as a “sensitive and strange young man,” “extremely ascetic, detached,” “monastically restrained” and “pale, delicate-looking.” Bill herself recounted how Woolrich had quietly proposed marriage while sitting two feet away from her on a couch. “You could have bowled me over it was such a detached proposal,” she burbled, “really unique, in contrast with the usual Hollywood pawing tactics.” While she found such behavior initially quaint, however, she was disenthralled when, two weeks after the wedding, her new husband still had not bedded her.

Ironically Woolrich had presaged this development with his novel Children of the Ritz, described by a contemporary reviewer as the story of a rich girl who makes a mismatched marriage and thereby pulls “down on her head an avalanche of newspaper publicity.” Disastrously for Woolrich’s own reputation as a naughty novelist and Jazz Age wonder boy, Bill’s annulment suit left him exposed, in a democratic decade which venerated the club-wielding “caveman” male, as nothing but a powderpuff. Rather than marrying, the article concluded witheringly, “it would have been better for Woolrich to have stuck to his typewriter.” Indeed, the author later co-dedicated his first crime novel, The Bride Wore Black (1940), to his trusty Remington portable, which had proven a far better companion than Bill. It is in Bride that an aggressive young woman gushingly tells the male popular novelist whom she is pursuing, “at least you’re like you should be….so many of the people who write red-blooded outdoor stuff are skinny anemic little runts wrapped in blankets. You at least cut a figure that a girl can get her teeth into.” It is hard to believe that the author did not have Bill and himself in mind when he typed this passage.

As Cornell with sadistic precision was emasculated in print, his opposite number Bill was admiringly portrayed as “beautiful,” “romantic,” “life-loving, vivacious, young,” someone who daringly took life by the horns while Woolrich meekly watched from the sidelines: “It was Gloria who handled the wheel…as they sped through the countryside in his expensive roadster. At the beach it was Gloria who dove into the crested rollers of the Pacific and swam far out in a glistening path….At the popular Coconut Grove night club it was Gloria who swirled gracefully with different partners upon the dance floor….”

Dramatically recounted as well was the story of how, just a few years before Bill’s and Cornell’s nuptials, when Bill was but sixteen, her father with a riding crop had thoroughly thrashed native Frenchman Gerard de Merveaux—a decorated Great War aviator and Hollywood fencing master who had become a friend of the family—after the volatile Frenchmen, who had a metal plate in his head, allegedly had threatened to murder Bill unless she consented to marry him. Newspaper reports from the time indicate that it was actually Bill’s former-actress mother Paula who had captured Merveaux’s amorous fancy (which she, then at the “dangerous age,” perhaps had reciprocated)—but that of course did not make nearly as good grist for Bill’s publicity mill.

Two attractive photos of “Glamorous Gloria” were included with the article, including her latest “camera study.” Readers were informed that Bill currently was in New York to launch a career on the stage. She was shortly to appear at the Morosco Theater in Marianne Brown Waters’ play The Blue Widow, Bill herself divulged. Asked her plans for the future, she airily speculated: “Well, you know how it is, once one has been on the stage. The theater—and that includes the movies—gets into your blood. I have a career ahead of me, I hope.” As for “other men,” Bill proclaimed she did not have time for that now: “That’s in the future tense.”

The cynic might speculate that Bill, now twenty-three, had herself puffed her annulment in the press—perish the thought–in order to help hype her acting career, which she had been struggling to get off the ground. (All her film roles had come to her courtesy of her doting parents.) One might even conclude that Bill, like the vengeful bride in The Bride Wore Black, was even getting a bit of her own back. Certainly the article could not have been more favorable to her and could only have been less favorable to Woolrich had it mentioned the queer matter of the sailor suit (assuming it ever existed). One has to wonder why Bill could not have quietly annulled the marriage three years earlier, in California, rather than at the New York Supreme Court, Manhattan in April 1933, with the press in tow. Even a gorgeous platinum blonde former Follies star, Hazel Eyeful (!), showed up at Bill’s hearing, coyly telling reporters that she was there “just to get the lowdown on how the wedding knot’s untied.” Her photo was included at the head of the article as well, presumably to add some eye-catching pulchritude.

As could have been expected, the resulting newspaper headlines were crushing for Cornell: “Novelist, ‘Mock Husband,’ Sued by “Unkissed Bride’,” gives the gist of them. In court Bill salaciously divulged that “she left her husband because their marital relations were a mockery,” before adding accusingly: “My husband tricked me into marrying him….After I discovered this deception there was no use to carry out the sham any longer, so I left him.” (At this point Judge Tierney circumspectly retired to his chambers with Bill and her attorney to hear the rest of her juicy tale.) After the annulment was granted Bill pronounced herself heartily glad that “the whole mess is over and done with,” but Cornell’s waking nightmare had just begun.

Of course Bill’s claim that it had been she who righteously left Woolrich when she realized that he would not or could not perform his conjugal duties directly contradicts her half-sister’s insistence that it was Woolrich who left Bill, devastating the blushing bride (as does Woolrich’s account; see below). Whoever left whom, however, there can be no denying that all this national publicity about Woolrich’s utter physical failure as a husband must have mortified the young author. They say there is no such thing as bad publicity, but this truism must have been cold comfort for Cornell after enduring the japing newspaper stories.

While Bill preened in the press, getting ready for her close-up, Woolrich fretted that the whole situation had brought the roof crashing down on his head, as it were, like an eruption from Mt. Vesuvius, imperiling his very mental health.While Bill preened in the press, getting ready for her close-up, Woolrich fretted that the whole situation had brought the roof crashing down on his head, as it were, like an eruption from Mt. Vesuvius, imperiling his very mental health. Like his harried character in The Black Curtain, he had “wanted to put walls around himself,” but a huff and a puff from Bill had easily blown them down; and now a news reporter was inside his very door, ravenous for juicy morsels of scandal. “We had a terrific fuss and Gloria left me,” the distraught author admitted. “I guess it was difficult for her to understand why I was so quiet. When she left the world fell upon me just as if there had been an earthquake. Now, I never want to write again. Please don’t think I’m seeking publicity in saying this. I am merely obeying my physician’s orders. He has warned me not to do anymore writing as it may bring on a nervous breakdown.”

Happily, Woolrich’s devoted mother Claire was helpfully on hand at their new place at the Hotel Marseilles, located in Manhattan at the corner of 103rd Street and Broadway about a mile from the old Tarler house, which the family had recently sold, to avow that she was determined to nurse her damaged boy back to health. “Since his babyhood he has been a victim of nervousness,” Claire confided. “Only a short time ago while Cornell and I were talking in our apartment, the door buzzer sounded. It startled me, but it so upset him that I was afraid he would leap out of the window—he is that highly strung. Of course I want him to take up his writing again, and although he seems to have put that quite definitely aside, I’m sure he will feel differently about when he is well again.” Claire then paused before asking curiously of this onetime rival for her son’s affections: “What is my son’s wife, Gloria, doing just now? You know, I have never seen her.”

Maternally Claire had done her part, as she saw it, for Cornell two years earlier, after he had returned to New York from California in 1931 to recover from the psychic wounds which his painful breakup with Bill had inflicted upon him. Mother and son had set out for a months-long tour of Europe, particularly France, where Cornell managed to complete Manhattan Love Song, the last of his six mainstream novels (although Francis Nevins argues the book should be deemed a crime novel). They finally left Europe in November, departing for New York from Le Havre aboard S. S. Westernland. Once back in New York, Woolrich actually lived apart from his mother in 1932, as he worked on another mainstream novel, this one set in Paris. Failing to find a taker for this one, he dejectedly threw the manuscript in an ashcan (according to his recollection) and moved in again with Claire.

Admittedly a certain Violent and Sebastian Venable vibe (recalling Tennessee Williams’ play) is evident from the mother’s and son’s entries on the Westernland’s passenger list, for both Claire and Cornell have falsified their ages, Claire admitting to having been born on November 29, 1883, making her forty-seven rather than the nearly fifty-six which she really was, and Cornell claiming to have first seen light on December 4, 1906, making him ostensibly twenty-four rather than twenty-seven. Claire had been subtracting nine years from her age at least since 1917, when, while traveling with Cornell on S. S. Monterrey, she claimed to be thirty-four rather than forty-three. Evidently Woolrich, following down his mother’s mendacious path, shaved three years from his age after 1917, possibly in order to make himself seem like even more of a prodigy when he published his first novel in 1926. However, when Woolrich writes in Blues that when his mother moved into the new Tarler house around the turn of the century (probably 1895/6) she was a teenager, he likely believed this was true, for, according to his mother’s own deception, she then would have been around twelve, rather than twenty-one. Would a good boy have doubted the word of his mother?

To my mind the entire annulment affair suggests the inherent ludicrousness of lurid tales of Woolrich—this solemn, desperately shy, mother-dominated, intensely nervous man whom everyone said looked barely more than a high school youth—and his gay sailor suit dalliances at the docks. In a newspaper interview with Woolrich conducted at the young man’s home by journalist Harold C. Burr in July 1927, after he had received acclaim for his novel Children of the Ritz, the author ingenuously confessed to Burr having been “frightfully embarrassed” when, on his first visit to a New York nightclub the previous year (with his mother, naturally), chorines dressed as cowgirls “roped him and drew him, chair and all, out into the middle of the floor,” laughingly exposing him “to the public eye.” “I’m never coming here again!” Woolrich wailed to his mother, who “cruelly laughed at his misery.” (One wonders whether Claire would have responded as blithely had Cornell been comfortable with the attentions of these bold ladies.)

Elsewhere in his interview with Burr, the twenty-three-year-old Woolrich, whom the journalist described as “so boyish we thought he had sent down a younger brother to say that the real Mr. Woolrich would be down in a minute,” reveals that after General Pershing led the U. S. Army across the Rio Grande into Mexico in pursuit of revolutionary leader Pancho Villa in March 1916, he, Woolrich, then twelve years old and living with his father in Mexico City, was frequently chased home from school by raucous gangs of rock-throwing Mexican schoolboys, intent on making a scapegoat of the half-Yankee boy. “I remember once when I was hit and the blood got in my eyes so I could hardly see where I was going,” Woolrich recalled, adding mournfully: “I didn’t get a great deal of schooling.”

The boyish author also told Burr of spectating at bloody bullfights in Mexico and evoked the horror of what happened to the horses, admitting ruefully: “My mother didn’t like it [his seeing that].” Yet Nevins, after quoting both Woolrich and his mother on the Bill Blackton affair as I have above, insistently concludes that “for obvious reasons [the mother and son] were less than frank.” Clearly in Nevins’ mind the salacious matter of the sex diary and the sexy sailor suit were settled law, as it were, and Woolrich stood condemned, his case unalterably closed. In the mind of Nevins and those he has influenced, seemingly, Woolrich has become the most notorious “gay” sailor since Brad Davis in Querelle or Alex Briley from Village People.

As for Bill/Gloria, her (very) minor part in The Blue Widow, a critically panned play which ran for only twenty-nine performances in September-August 1933, seems to have been the apex of a stillborn stage career. Two years later Bill, now twenty-five, in Manhattan married William Jacob Bowers and returned with him to California, where he worked as a story editor successively for Columbia and Paramount. Bill Blackton Bowers bore the couple three children before expiring in Pasadena at the age of fifty-four in 1965, three years before Woolrich’s own demise. At Bill’s death her greatest moment of fame remained having brought an innuendo-laden annulment suit against a semi-celebrated “naughty novelist.”

Marian Trimble informed Nevins that in contrast with Bill’s union with Woolrich, her “second marriage was a beautiful and happy one,” leading Nevins to conclude piously (paraphrasing a Woolrich character) that “decent people don’t always get it in the neck.” Meanwhile Woolrich recovered enough from his nervous prostration to reinvent himself as a crime writer. He published his first pulp crime story, a nasty little number called “Death Sits in the Dentist’s Chair,” in Detective Fiction Weekly in August 1934, a little over a year after his national humiliation had led him dramatically to abjure writing. Perhaps it had been inspired by a business visit to his mother’s prominent dentist cousin. In any event, it was the first of more than one hundred pieces of short crime fiction that Woolrich would publish in the crime pulps during the 1930s. The humble pulps, it seems, provided the author with a mouse hole in which he could safely hide while exploiting for profit his darkest obsessions and inhibitions—which may or may not have included homosexuality. Bitten once and now twice shy, Woolrich would shun publicity for the rest of his life.

****

How is the self-loathing homosexuality which Francis Nevins believes to have been the black wellspring to Cornell Woolrich’s unique writing genius reflected in the author’s voluminous crime fiction? Here are examples from Dream of what Nevins terms “homosexual symbolism” in Woolrich’s work:

“‘I was carrying Death around in my mouth,” the reporter tells us near the end [of the story “Death Sits in the Dentist’s Chair,” where a dentist fills cavities with cyanide], and if one is determined to find subtle traces of Woolrich’s homosexuality everywhere in his work, one might as well begin here. (p. 129)

While struggling with Cook over a gun, the hobo is shot in the mouth (here we go again, homosexual symbol seekers!) (p. 141)

….they arrange for a pickpocket accomplice to take a ride on the same train that is bringing Bull to the state pen, sit in the seat behind the mobster and quietly puncture Bull’s rear end with a hypodermic full of germs (homosexuality symbol hunters take notice!) (p. 157)

All these instances seem reductive to my mind–not to mention remarkably puerile and in dubious taste. Since Woolrich was a gay man, so the reasoning seems to go, inevitably any time in his tales when poison, bullets or germs enter a man’s mouth or buttocks it symbolizes homosexuality. In this juvenile egg hunt for “homosexual symbols” Nevins focuses relentlessly on sex acts. Is it Woolrich who associated gay sex with death or is it Nevins who has imposed this meaning on Woolrich’s texts? Dream appeared in 1988, at the height of the AIDS epidemic in the United States, something which may have influenced Nevins’ take on this matter. Yet unless he was endowed—like his seer character in Night Has a Thousand Eyes/”Speak to Me of Death,” with second sight—Woolrich could not have foreseen this calamity.

I have read my share of Woolrich (granted, Nevins has read everything, as Dream makes abundantly clear) and for my part I cannot say that in the author’s work I am strongly struck by intimations of same-sex attraction on his part. Woolrich often does write well from a woman’s viewpoint, but he writes convincingly from a tough male viewpoint as well. Seemingly absent from Woolrich’s fiction is the sustained interest in the male body which I have found in the work of gay male vintage crime writers like Hugh Wheeler and Richard Webb (aka Patrick Quentin/Q. Patrick/Jonathan Stagge), Rufus King, Milton Propper and Todd Downing. I am powerfully struck in Woolrich’s work by an aching depiction of loneliness, despair and doom, yet, Nevins notwithstanding, this is not a state of mind which is specific to gay men. Any person, whatever his or her sexual orientation, might have these feelings and give expression to them in fiction.

Given Nevins’ writing about Woolrich, it is not surprising to see that he authored an 1977 article about Milton Propper, identifying him as another “tragic” homosexual, and that in a 2010 Mystery*File article he condemned Patricia Highsmith along the same lines as Woolrich, whom he passingly denigrates in his harshest terms yet: “If you think Cornell Woolrich was something of a psychopath and a creep, you don’t know the meaning of those words till you’ve encountered Highsmith. Both, of course, were homosexual. I gather from [Joan Schenkar’s biography] that Highsmith…was never terribly comfortable with being a lesbian….Woolrich was perhaps the most deeply closeted, self-hating homosexual male author that ever lived.”

If you are sensing an invidious theme here, I would hazard to guess that you are right. Elsewhere in Dream Nevins refers passingly to “the special agonies of the homosexual whose religious roots are Catholic” (Woolrich’s father had been a nominal Catholic and Woolrich adopted the faith, at least nominally, near the end of his life); and he speculates that Woolrich and Catholic film director Alfred Hitchock, who adapted a Woolrich short story as his renowned flick Rear Window, shared the same dismal world view—that the world was “a hideous and terrifying place”—on account of their “longing for physical relationships which the obesity of the one man and the homosexuality of the other seemed to put forever out of reach.” Evidently both stoutness and queerness constituted crippling hurdles to human happiness in Nevins’ mind.

When gathering such black pearls of wisdom about members of the queer community in my basket of literary boners, I am frequently reminded of the morbid line from the pioneering if at times problematic queer film The Boys in the Band, which premiered in March 1970, just a year-and-a-half after Cornell Woolrich’s death. “Show me a happy homosexual and I’ll show you a gay corpse,” pronounces one of the film’s characters. (Yes, this character is a self-loathing, lapsed-Catholic gay man.) In his writing about Woolrich and other crime writers whom he deems to have been queer, Nevins seems to have drawn this dismal credo deep into his heart.

In support of his self-loathing homosexual thesis in Dream, Nevins also draws on an interview he conducted in 1979, two years after his interview with Marian Trimble, with Lee Wright, an important, trailblazing early woman editor of mystery fiction at, successively, Simon & Schuster and Random House who accepted Woolrich’s first crime novel, The Bride Wore Black.Theirs’ was a strictly professional, not intimate, relationship, Nevins primly assures us, since “Wright was a married woman and Woolrich a homosexual.” Wright, who readily admitted that she found her moody author an exceedingly trying man to deal with (“I still think he was a little crazy….I was afraid he would throw me through the window someday.”), compliantly confirmed for Nevins the “fact” that Woolrich was gay. (A fuller version of the Nevins-Wright interview can be found in Nevins’ “Memories of a Haunted Man” in the May-June 1984 issue of The Mystery Fancier.)

Wright revealed her own personal bias when, upon Nevins asking her how Woolrich felt about his mother, she proceeded vigorously to unpack a suitcase full of belittling, pseudo-Freudian gay stereotypes from her era. (There was no sailor suit in this one, however.) “[His mother] was pretty terrible too. [Woolrich] had an unnatural relationship with his mother…the true picture of a homosexual’s relationship with his mother,” the agent breezily explained. “A combination of dependence, adoration, hatred; all the things you’d expect.”

Writing of Woolrich’s life in the 1950s Nevins glibly pronounces that the author “left the Hotel Marseilles (where he lived with his mother) almost never, just to get a haircut or a few drinks, or perhaps to see a movie, or for sex.” He bases his notion of the sex-seeking middle-aged, mid-century Woolrich on an anecdote from Wright about how, sometime in the 1950s, she invited Woolrich and Robert Greenan, a Simon & Schuster sales representative (since deceased), to dine with her at her apartment, her husband being away. “I thought it would entertain Cornell, and it would certainly entertain Robert to meet Cornell,” she explained, the eccentric author being such a “character.” Around eleven that night, the two men left Wright’s apartment together. Afterward Greenan told Wright that he had faced “a terrible time protecting himself from Cornell on their way home on the Elevated. It almost amounted to a physical attack, because he was so eager to get at Bob.”

So we are to understand that the “pale, puny, homosexual recluse” who, according to Wright herself (see below) was “too shy” in social interactions, sexually assaulted another man on the Elevated? Had he taken the sailor suit out of mothballs for the duration of the ride? That Wright’s take—or, for that matter, Greenan’s, for all of this is hearsay all over again—might have been a misreading of the incident seems never to have occurred to Nevins. Instead there ensued this telling exchange (not included in the book), where Nevins appears to prompt Wright to affirm a conclusion he already had reached on his own (that Woolrich was a closeted gay man consumed with “homosexual self-contempt”):

Nevins: Was that [sexual assault] something Cornell did a lot to men?

Wright: Apparently.

Nevins: No wonder he wasn’t too well liked.

Wright: Some men can be very cruel in rejecting a man.

Nevins: The interesting thing is that there are some incidents dealing with homosexuals in some of his writings….In Manhattan Love Song…the main character, who’s a typical Woolrich loser, falls in love with this strange woman. He desperately needs money to get them both out of the city, and he beats up and robs a homosexual actor who is portrayed by Woolrich with utter contempt.

Wright: That’s what he had for himself, utter contempt. Exactly the right words.

Nevins: You can sense that. If you don’t know Woolrich’s life it just sounds like the Archie Bunker point of view, but if you do know Woolrich you know he’s writing about contempt for himself.

At one point in this interview Nevins suggests with rare critical modesty that he cannot really judge how Cornell Woolrich portrays women in his crime fiction, because “I don’t really have the right to that opinion….I’m the wrong sex….” Yet Nevins, presumably a complacent straight man, evidently sees no similar problem with his attempting cumbrously to climb into the complicated mind of Cornell Woolrich, a man whom, like some antiquated 1950s psychiatrist, he repeatedly analyzes (and belittles) as a self-hating homosexual. (Speaking of antiquated, for the last half century the clinical term “homosexual” tellingly appears to have been Nevins’ sole word for a person who feels same-sex attraction.)

Over the years author Barry Malzberg, Woolrich’s literary agent at the terminus of the crime writer’s life, has blasted Nevins’ take on Woolrich’s sexuality. In his 2012 introduction to Centipede Press’ edition of Woolrich’s Phantom Lady, Malzberg writes bluntly of his “sheer exasperation with Frances M. Nevins’ incessant fag-baiting in his otherwise bibliographically useful biography of Cornell.” What Malzberg calls his earlier “bleat of protest” was made in the magazine Mystery Scene in 1992, in a piece entitled “Presto: Con Malizia.” Therein he writes:

Nevins is convinced…that Woolrich was a practicing homosexual and that his fiction…was wholly framed by his sexuality, that the fiction can only be understood or appreciated in terms of a condition which Nevins regards as pathological….The only evidence which he was able to produce (we had extensive correspondence about this in the late seventies and early eighties) was a poorly recorded, almost inaudible cassette recording of an interview Nevins stated that he had conducted with Woolrich’s sister-in-law….Two (or counting Nevins) three levels of hearsay were invoked and none of them constituted the kind of evidence which would stand up in a court of law for five minutes.

As for Lee Wright’s testimony, Malzberg continues: “I knew Lee Wright and she thought a lot of people were homosexuals and liked to say so. Many of them who she chattily named are alive but one other of them is dead: Raymond Chandler.” Ironically there seems to me to be more material suggestive of latent homosexuality in Chandler’s work (see The Big Sleep and Farewell, My Lovely, for example) than in Woolrich’s, yet I do not believe that Chandler was gay, even latently so; and I doubt that Wright had firm grounds for so believing.