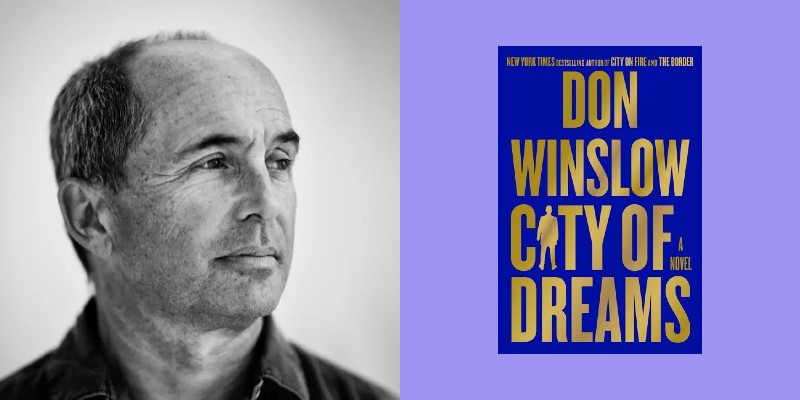

Don Winslow has written his last novel. That was the unavoidable takeaway from our latest conversation, which came in the weeks before the release of City of Dreams, the second installment in Winslow’s trilogy following the life and times of Providence’s Danny Ryan. The new book, picking up after a bloody gang war, takes Ryan and company west, orbiting around a splashy Hollywood adaptation of their recent exploits. The story follows a structure tied to Greek epic poetry, conveyed through Winslow’s knowing, streetwise prose, all with a relentless sense of momentum powering toward the next tragedy in the sequence. Which brings me back to that first revelation. Winslow is on the record: he’s retiring as a novelist after this latest trilogy is done. Talking with him, I found out that third novel is already written. Winslow exuded a cool confidence discussing the decision to hang it up and what’s next.

(You can read our conversation about City on Fire, the first novel in the trilogy, here.)

Murphy: With City of Dreams, you’re still working in the idiom of epic poetry. Can you situate me in the legend? Where are we picking up with this book, vis-à-vis the Greeks and Romans?

Winslow: It’s the beginning through the middle of the Aeneid. When you talk about, for lack of a better term, the Trojan Horse cycle—the Iliad, the Odyssey and the Aeneid—it was always my intent to follow Aeneas through his life cycle, but that starts in the Iliad, where he’s a minor player, which for me was book 1, City on Fire.

We all think of the end of the Trojan Horse story as being told in the Iliad, but it’s not. It’s actually Aeneas who tells us that part of the story, when Dido asks him about his life. Aeneas says, ‘Sorrow, unspeakable sorrow you ask me to bring to life once more, my queen.’ Obviously, the through line of the book is Danny, our Aeneas. He loses the war and has to leave with his increasingly senile father and infant son and what’s left of his crew and wander for years and years.

I was fascinated by what happened to certain characters after the Trojan War ended. It’s really a noir novel if you follow Agamemnon. He goes home, and his wife has blamed him for the death of their daughter. She and her lover kill him in the bathtub.

Murphy: It’s a James M. Cain novel.

Winslow: Exactly, and that’s in the Greek dramas. The Oresteia cycle of Aeschylus. When I read them for the first time, I thought, Jesus, it is, that’s a James M. Cain novel.

Murphy: For a writer, there must be something liberating knowing you’re working with a classic structure: a story that has meant something to humans for thousands of years.

Winslow: There really is. That was the whole idea behind this trilogy. These stories, whether people are aware of their influence or not, are so pervasive. They’re in our culture, our stories, our folklore, our language even. Tapping into that, you have at least a rough idea of where you’re going.

The challenge, which was also fun, was to come up with plausible modern equivalents. What’s a Trojan Horse in Providence? Who’s Aphrodite? Who’s the Queen of Carthage?

Early on the Aeneid, Aeneas, washes up on the shores of Carthage and walks into a cave. On the cave walls are murals of the Trojan Horse story: of Aeneas himself, his friends, his dead wife. What’s the modern equivalent of that? The answer is film. So, they’re making a movie of the first book, and I thought it’d be fascinating to get Danny onto that set.

Murphy: The first parallel I thought of with Danny working his way into Hollywood was Get Shorty. This is a very different approach, but whether it’s a comedy of manners or a crime epic, there’s something fundamentally satisfying for the reader about watching a gangster get involved in movies.

Winslow: It’s an old story: gangsters in Hollywood, the symbiotic relationship between them, and the quite amusing—to me—dynamic where producers and directors who make gangster films suddenly think they’re gangsters. I was just having fun with it. I think I wrote those sequences twenty years ago. I’ve been around a few laps in the Hollywood pool, with some success and some notable failure. All of a sudden I was writing, and I had those two guys, the Altar Boys, go up to the set, because I thought, just the craft services table would keep them there, they’re like raccoons. My books have been under option since 1991. I’ve been to those Hollywood meetings and on set and on location and had films made and not made and watched all this go on. I was just kind of amused at putting those two guys up and watching them glom onto a production and suck it dry.

Murphy: You also get a chance to give readers a brief history of mob interference in the movie industry.

Winslow: The mafia in LA was always relatively weak compared to New York or Chicago. I forget the FBI official who famously called it the Mickey Mouse Mafia. But they did make several attempts to infiltrate the unions that are associated with the film industry. They made a little progress, then they got shut down pretty quickly.

Murphy: You mentioned that this is a story you’ve been working on, off and on, for decades. How did your relationship with Danny Ryan evolve?

Winslow: When I first started writing Danny, I had a five-year old kid. Now he’s a thirty-three year old. So, by the time I came around to writing the third book, I saw fatherhood from a completely different angle. You gain a greater appreciation of the importance of family and what it means in your own life, and therefore what it would mean in Danny’s life.

Murphy: I was particularly interested in Danny goin on the lam as the father of a toddler. You have to think about who’s going to get that meal ready, how the laundry will get done. You don’t see much of that in crime fiction.

Winslow: I really wanted to tackle that because you don’t see much of it. There were practical considerations. If I’m following Aeneas’ life track, that’s his problem, he’s out there with an aging father and a baby, and he’s a single dad and he’s a fugitive. And he’s out of money. You gotta hide, you gotta get a job, gotta get a babysitter, gotta get breakfast out. That stuff has to get done.

Murphy: Do you still intend for this trilogy to be it for you? You’re retiring?

Winslow: Yeah.

Murphy: Why?

Winslow: A couple reasons. One I’ve sort of gotten involved on social media with political folks. There’s only so much time and energy. And second, I think I’ve told the stories I wanted to tell. This trilogy is the work of a lifetime. Coming on top of twenty-six years on the drug beat and writing three big fat books about that, it’s just time.

Murphy: Will you really be able to give it up?

Winslow: Yup.

Murphy: You sound confident.

Winslow: I’ve made my decision. It wasn’t an easy decision to make. I took my time with it. Once I make decisions, I’m usually pretty firm with them. And watching the news, I think democracy is in an existential crisis here, and I don’t just want to be writing elegies for our democracy. So, I think time and energy at this point needs to go somewhere else.

Murphy: You mentioned before that the third book is already done. So, you’ve written your last novel?

Winslow: Yes, I have. I know, it sounds strange to me, too.