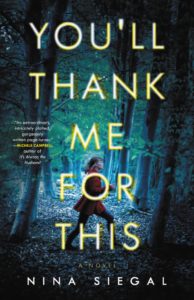

The idea for my latest novel, You’ll Thank Me For This, came from an article in The New York Times about a Dutch tradition known as “droppings” in which tweens and teens are blindfolded and left in the woods and expected to find their way back using only rudimentary tools such as compasses, maps, the wind and the stars—obviously no smart phones or modern GPS devices.

Although I’ve lived in the Netherlands for 15 years, I had never learned about droppings, and although I do contribute regularly to the Times (about art and culture) from here, the article was written by a colleague, Ellen Barry. I asked around and lots of my friends had done a dropping in their youths; their kids were still doing them, too, often as part of Scout training.

I’ve written novels before—I was never a suspense writer—but it struck me that this was an excellent premise for a thriller, right in my own “back yard,” as it were. I had a flash of just how to write it—from alternating perspectives of a mother and daughter, and it happened that I had a 12-year old girl, my step-daughter, living with me at the time. The structure of the book came quickly, and once I sat down to write, it came rushing out like a storm.

What drew me into the story was the fact that “droppings” illuminate a kind of cultural difference that is so nuanced that many people might not recognize it as worthy of mention. Barry’s piece had caught Dutch people by surprise as well, judging by the multitude of Twitter remarks it engendered, many of them mocking. They took issue with the idea that anything about “droppings” was unusual.

The Dutch, a largely Calvinistic pragmatic folk in a prosperous, modern, socially progressive, fiscally conservative country, see themselves as very ordinary. They don’t really believe that they have any esoteric traditions (though their tradition of Sinterklaas, a Dutch pre-Christmas celebration that involves a blackface character called Zwarte Piet has been the subject of enormous controversy), and pride themselves on their “normalcy.” The Dutch expression, “Doe normaal,” or, “Just be normal,” is the Dutch national motto.

Few people that I know here think that leaving your kid, in the company of other kids, in the forest for a few hours and letting them find their way home is any big deal. This culture, as I have observed while raising kids here, takes a far more laissez-faire attitude towards parenting than we do in the United States.

Or, as Barry put it, “The Dutch—it is fair to say—do childhood differently.” I’m not sure how much of that comes from the fact that the Netherlands is generally a very safe country, flat and low, with few places to get lost, or whether it’s just a matter of an attitude that kids need to learn self-reliance, and parents shouldn’t hover.

I grew up in New York City in the 1970s, and later, in the suburbs of New York. Different time, different place, of course. But I do distinctly remember one occasion when I was about 13 years old and I opted to walk home alone from a friend’s house, about 20 minutes away, instead of calling my parents to pick me up. There was a park with a nice woodsy trail I could take almost directly home, and I thought it would be nice for me to figure it out without my parents. By the time I arrived at my house, though, I found my entire family in a shrill panic, the police alerted, my friend berated, because of the terror that I had inspired by being alone in the woods!

As a parent, today, I can certainly understand where that fear comes from — especially when a young girl is involved, especially in the environs of New York. But I’ve also become more comfortable with the slightly more lax Dutch manner of parenting. For us, kids grow up running free among hundreds of goats in a goat farm, or play for hours in nature playgrounds that involve a lot of rickety ladders, rope swings suspended over water, and plenty of mud.

My step-son had his 10th birthday party in a park where kids could build wood structures from scratch — with hammers, nails, saws strewn about haphazardly everywhere on the ground — and build giant bonfires. There was one adult supervisor for every two dozen kids, while the parents were busy chatting and drinking in a cafe nearby. That park, I’m sure, would make most American parents apoplectic, not to mention that it would never exist because of all the potential lawsuits.

Let me be frank: no matter how long I live here, this kind of laxity does still freak me out, even if I do prefer it to helicopter parenting. And the idea of sending my now-eight year old daughter into the forest at night with other kids, four years from now, does make my stomach lurch. That’s why, for me, it seemed like a great backdrop for a thriller. In my mind I imagined something, somewhere, between Stephen King’s Children of the Corn, the Blair Witch Project, Little Red Riding Hood, and The Chain, by Adrian McKinty.

I wanted to see if I could find a way to make the dropping tradition not only scary to Americans, who might naturally find the practice rife with fear, but also to my Dutch contemporaries, who might otherwise just shrug their shoulders in perplexity. After all, I wanted my Dutch friends to read it too, and to be convinced that there are scary things out there in the Dutch woods.

For me, that meant raising the stakes on the dropping for Karin, my 12-year old main character, and her mom, Grace, who, like me, is an American who has lived for a long time in Dutch culture.

Partially for that reason, I decided to set it in an imposing landscape, the Hoge Veluwe National Forest, which is one of the only wild nature reserves in the Netherlands, and a place I’ve had the pleasure to visit many times. It’s not only expansive, picturesque, and sometimes breathtaking, but also, in some places, very spooky, with desert-like sand drifts dotted with gnarled trees that look like desiccated corpses. Personally, I wouldn’t want to be out there alone at night.

Then I wanted to poke some holes in the idea that the Netherlands is a really safe place, and to incorporate some of the true dangers that were currently topical. Drug smuggling and sex trafficking, due in part to certain lax drug enforcement here, are obvious potential sources of danger in this country, but I didn’t want that to be the main issue.

Then, there are the natural dangers. As it happened, there was a wolf in the Hoge Veluwe. He had arrived from Germany recently—a lone wolf, and in the time I was writing the book, he had somehow found a mate and started a family. It was too good, too apt, not to include it in my modern Little Red Riding Hood story.

Ultimately, however, the dangers that raised the stakes of my story had to come from inside the characters themselves. What would make this particular forest both inviting and more frightening for Karin, and what would make the whole trip a lot less comfortable to her mom, Grace? What were the personal factors amping up the fears, and what if these fears were propelled forward by certain other outside factors? For me, this is ultimately what propelled the suspense of the book, not the backdrop or the cultural tradition, but the life inside the characters themselves.

***