Before I embarked upon my first ever fiction, I was a writer of non-fiction, of articles, essays, and anything else I could think of to get published. To keep a roof over my head, I also had a day job in outside sales, which gave me an income and a framework to my day, and to be honest, I had the job where I wanted it—I could work my own hours provided I met my targets. The bonus of hard work and good results was more writing time each week, though a magazine assignment sometimes meant clambering out of bed at three in the morning to interview someone in a far-flung country.

One day, stuck in traffic on the way to work, waiting for the cars ahead to move, I had an idea for a novel and a leading character—it was a moment of artistic grace, because by the time I arrived at work I had most of her story in my head. I wrote the first chapter that night. The character was a woman named Maisie Dobbs—the title of my first novel.

I didn’t stop to consider such things as “genre” or “series”—I just wanted to write the story that had come to me while stuck in that traffic jam, about a WW1 nurse, who later became a trained psychologist and investigator. I knew she was no amateur and that her approach was unusual. I knew who her fellow characters were and I knew she represented the spirit of her generation of women in Britain—the first generation of women in modern times to go to war. So I wrote the story that was in my head. I didn’t consider it a mystery—in fact beyond referring to it as “my novel” I didn’t assign a category to the work. Following the surprise of landing an agent and then an editor, imagine my additional shock when I was asked for the next book in the series. Fortunately I had some ideas up my sleeve.

My publisher arranged for me attend a convention for mystery writers and readers—I had no idea such events existed. I attended some panels and was taken aback to realize that there were different categories within the “genre”—cozy, traditional, thriller. And that’s just the start. Seasoned authors talked about the “three act format” and other elements of the mystery, such as how many pages should elapse before this or that event happens and when the villain should be introduced. I had no idea about these things, and realized that I had written a novel that was, by those standards, a bit weird. Yet I had enjoyed writing my novel, playing with time, moving back and forth through history as I developed the narrative, and I’d allowed the characters to open up the plot because, frankly, I did not know how to “plot.” I had never made any sort of formal plan for the story, though I had an idea of how I should pace the beginning, the middle and the end—but along the way I had broken every so-called rule in the book. I called my husband in a panic, explaining that I’d not followed the rules of mystery, and fortunately he said, “I wouldn’t worry about it, if I were you—just keep on doing what you’re doing.”

It was at another conference that a panelist bemoaned the sort of critic who would describe a well-crafted mystery as “transcending the genre.” I remember him saying, “What is that supposed to mean anyway? What should surprise reviewers about a mystery that can also be considered literary fiction?” Others commented on the fact that there are authors of general/literary fiction who write occasional mysteries, yet they are never referred to as “mystery writers”—a successful writer who has hitherto written lauded mysteries might publish a work of literary fiction and be treated as if they had been revealed to be a genius, rather than the novel accepted as another work by an accomplished author who takes their craft seriously. I have found some of the finest literary fiction on bookstore shelves labeled “mystery.” I’ve also discovered my novel, The Care and Management of Lies, shelved in the mystery section of bookshops, yet it is not a mystery—not even a whiff of one.

The comments from the panelist at that first mystery convention remained with me, but not in the way you might imagine. I never made any brave attempts to “transcend the genre”—but I knew I wanted to stretch myself with each novel in my series. I wanted to try different approaches and I’ve done that with time and place. I took a leaf from the thriller writer’s playbook for Among The Mad, where every scene had a date stamp, a countdown to finding a very damaged, dangerous man. I have set a novel in a rural location, allowing the narrative to reflect the rhythm of life on the land, and I have plunged my characters into the midst conflict—the Spanish Civil War in A Dangerous Place; the threat of pre-war Nazi Germany in Journey To Munich.

Sometimes I see myself as a sort of master puppeteer, setting my characters in often challenging situations and then seeing what they do, how they conduct themselves, along with the personal outcome of their decisions. Delving into character and the connections between people caught at the turning points of history has become the most important aspect of my work as a novelist—from there I just have to trust that plot will open up like a map as my words fill the page.

One of the reasons I was bewildered by comments heard early in my journey as a novelist—comments that questioned the literary integrity of the mystery—is that the form offers an extraordinary creative opportunity for the writer of fiction, because it is rooted in the classical, archetypal journey through chaos to resolution. I have never followed any so-called “rules” as I go about the process of developing a story and I never tried to write to a given number of acts—the notion of the three-act narrative still mystifies me. Yet I am inspired by writers of mystery who in their work have explored every human condition and emotion, and who have brought thorny issues to light with their stories, tackling environmental justice, organized crime, war, peace, politics, love, grief, childhood, old age, immigration, and the challenges of our time. Above all, as a reader and writer, I have found in the mystery the essence of what it means to be human at the very best and worst of times.

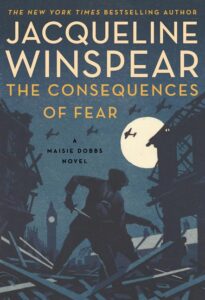

As I create the framework for a novel, I am often drawn to a theme. I delved into the issue of fear for The Consequences of Fear, my latest book featuring psychologist and investigator, Maisie Dobbs. Fear is such a compelling subject, a powerful emotion I’ve had to face on a personal level in recent years, so I wanted to explore the experience of fear creatively, once again sending my characters into the eye of the storm—into the mystery of chaos, and the arc of story.

***