It’s possible, perhaps, to feel sympathy for Norman Bates. Mental illness and a manipulative mother drove him to murder and other horrifying hobbies even while, as a small business owner, he struggled to maintain a tiny roadside motel bypassed by progress.

It’s less easy to feel sympathy for Leatherface, generally assumed to be mentally deficient and (also) easily manipulated by family members. But his history included not only gainful employment in a slaughterhouse but as an outsider artist, fashioning sculptures and mobiles from bones as well as sewing unique facial coverings.

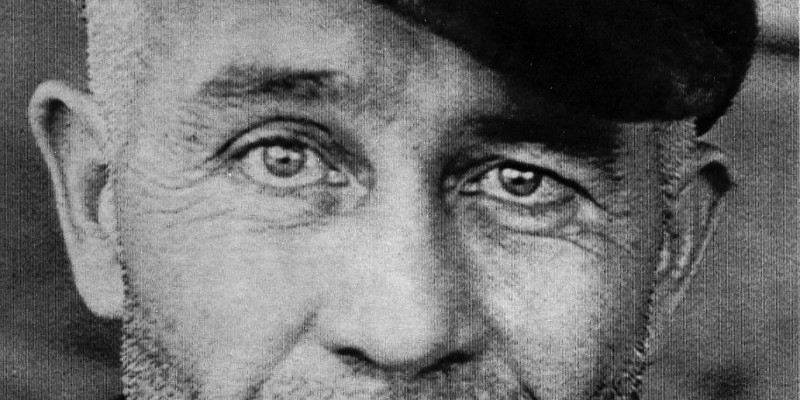

Described in such a way, the central characters of “Psycho” and “Texas Chainsaw Massacre” seem like pitiable figures. The two are certainly among the most vivid in pop culture history of the past 75 years and both are drawn from Ed Gein, a Wisconsin man who made headlines around the world in 1957 when his gruesome crimes were discovered. Gein’s story, fictionalized, reached millions of people when Robert Bloch’s novel “Psycho” was published in 1959 and turned into a classic thriller film by Alfred Hitchcock in 1960.

Gein’s story has been reported in books, a notorious underground comic and a recent graphic novel. It’s as fascinating and repellent a story as has ever been turned into popular fiction.

Thirteen years before “Eddie” Gein’s most gruesome crimes were discovered, came what was likely Gein’s first murder, with the death of Gein’s brother, Henry.

Dreadful child, domineering mother

The village of Plainfield, Wisconsin had always been a quiet place. The community’s population was only about 600, so it was likely everyone in the area knew the Gein family. Edward Theodore Gein was born on August 27, 1906 to George and Augusta. George farmed and, for a time, ran a butcher shop. Augusta, a harsh and sex-averse woman – according to Harold Schechter’s 1989 book “Deviant: The Shocking True Story of Ed Gein, the Original Psycho” – had already given birth to a son, Henry, born in January 1902.

Ed Gein would recall, decades later, that he could never please his mother and that she called him “a dreadful child.” At school, other kids teased Eddie about his soft voice, his feminine mannerisms and his sagging left eyelid. Schechter writes that Henry and Eddie grew accustomed to their mother’s tirades, among them regarding the wickedness of women. Their father was possibly worse, regularly getting drunk and whipping the boys. When they weren’t being insulted or beaten, Augusta made the boys swear they would never be “contaminated” by women.

Mercifully for Henry and Eddie, George Gein did not linger long into his sons’ adult lives. He died in April 1940, leaving Augusta time to focus on domineering her now-adult sons.

You’d think the brothers, being on the receiving end of lifetimes of abuse both physical and verbal, would grow closer. But on May 16, 1944, Henry and Ed were dealing with a fire on the family property. Schechter’s book says that by some accounts, the brothers had set the fire to clear dry grass. Some thought the fire had been started by accident.

Eddie reported to police officers that he had lost track of Henry while they were trying to manage the fire. But he led them to the spot where his older brother lay, in an area that had been scorched by fire. Henry didn’t appear to have been touched by the flames, but his head showed bruises. The police theory was that Henry had been overcome by smoke and collapsed and hit his head on a rock. It would be more than a decade, after Ed Gein’s most notorious crimes had been discovered, until people began to reassess what might have happened to Henry Gein.

For her part, Augusta Gein survived her oldest son by a little more than a year. She grew sick and, under Eddie’s care, lived only until late 1945.

For the first time in his life, Eddie Gein was alone.

‘She’s at my farm right now’

Over the next decade, Ed Gein and his family farm were both largely untended. The farm lay fallow while Eddie hired out to work for other farmers. Mild-mannered Eddie, now in his 40s, seemed to quit bathing and shaving and spent more time alone – when he wasn’t ogling the farmers’ wives and daughters who served lunch to farmhands for hire like him.

Schechter’s book recounts how Ed Gein, even as he neglected upkeep of his farm and himself, began to study macabre subjects. He devoured books about Nazi atrocities and South Seas cannibals and headhunters, taking particular interest in how shrunken heads were made.

At the same time, Schechter notes, Wisconsin police were dealing with a rash of disappearances of people, particularly women and girls. Among them was Mary Hogan, a tavern owner who vanished in December 1954. Blood was found on the floor of her tavern, but she was simply gone. In the wake of her disappearance, when men would tease Eddie that he should have courted the woman, he replied that she wasn’t gone.

“She’s not missing,” he responded. “She’s at the farm right now. I went and got her in my pickup truck and took her home.”

For Ed Gein, the saving grace in being an oddball who said oddball things was that few paid any attention to what would later prove to be his confession.

Those around Eddie weren’t the only ones who, even if they had been paying attention, would be inclined to write things off as simply Ed Gein being Ed Gein. Local teenagers said that Eddie had shown them shrunken heads. Eddie claimed the heads were sent to him by a cousin who had served in the Philippines during the war. Rumors intensified after boys who had been in the Gein house recounted seeing heads – not shrunken – hanging in a room. The boys convinced themselves that they had seen Halloween masks.

As the Gein farm gained a reputation as a haunted place, rumors were intensified by reports that, late at night, people passing the remote homestead swore they saw long-dead Augusta Gein in the yard, dancing naked in the moonlight.

On November 16, 1957, on a day when most of the men of Plainfield were out hunting and the women were tending to their homes or shops, Ed Gein went to Bernice Worden’s store, where many of the townspeople shopped. Eddie went into the store seeking a refill of a jug of antifreeze. Before long, he had killed Bernice Worden, taking her body and leaving blood on the floor, just as had been the case with Mary Hogan three years before.

When Bernice Worden’s disappearance was discovered, suspicion immediately turned to Gein due to his oddball ways. A group of men were dispatched to find Gein and search his property. Eddie was found at a neighbor’s house, and he immediately implicated himself by admitting that he knew he was a suspect in the shopkeeper’s disappearance.

As for Bernice Worden, officers found her hanging upside-down from the rafters of a barn on the Gein property, dressed out like a deer: Her torso was split and her head had been cut off. A photo of the horrific state of Worden’s body was published in “Edward Gein: America’s Most Bizarre Murderer,” a 1981 recap of Gein’s trial, written by Robert H. Gollmar, the judge in the case.

The list of body parts found in Gein’s possession – everything from bowls made from human heads to a wastebasket made from human skin to Mary Hogan’s face, kept in a bag, and her skull, kept in a box – is appalling. Lips on the drawstring of a window shade and nine vulvae kept in a shoe box, for god’s sake.

It seems Gein’s hobby wasn’t limited to Worden and Hogan. He had been robbing freshly-filled graves of bodies. Gein told investigators he’d raided graves 40 times. He especially favored digging up the remains of middle-aged women because they reminded him of his mother.

He had, authorities found, assembled skin suits that he could wear.

Eddie Gein’s case and his subsequent big-screen fame could be cited as the ultimate example of truth being stranger than fiction.

Ultimately, a trial – with Judge Gollmar presiding – was held and Gein was found not guilty by reason of insanity and was ordered to spend the rest of his life at Wisconsin’s Central State Hospital for the Criminally Insane.

Eddie lived until he was 77 years old, dying July 26, 1984 as a result of lung cancer. But his notoriety was long-lasting and began decades before his death and lasted decades after.

A twisted tale for a notorious author and director

Robert Bloch and Ed Gein were perhaps the perfect match. Both had spent time in Wisconsin, for one thing. Bloch was a writer of renown before he published “Psycho” in 1959. By the time the book came out, Bloch was known for noting, “I have the heart of a small boy. I keep it in a jar on my desk.”

When “Psycho” was published by Simon and Schuster on April 10, 1959, that anecdote was cited in newspaper stories and columns to show Bloch’s irreverent and macabre sense of humor. And there is probably humor to be found in Bloch’s book, but it is a mostly straightforward tale of horror.

If you haven’t read the book, you should know that Hitchcock’s movie, scripted by Joseph Stefano, follows it quite closely. But for a sampling of Bloch’s black humor and one tidbit that isn’t detailed in the movie, look no further than the chapter in which Norman Bates – overweight in the book, not lean and young like actor Anthony Perkins – kills Mary Crane (whose first name was changed to Marion for the movie version):

“Mary started to scream, and then the (shower) curtains parted further and a hand appeared, holding a butcher knife. It was the knife that, a moment later, cut off her scream.

“And her head.”

The Boston Globe was not impressed.

“Very strange story about a homicidal maniac somewhere in the Middle West,” the paper’s Avis DeVoto noted in a capsule review. “Psychologically ineffective but so full of horrors it can scarcely be recommended as entertainment. The author plays an outrageous trick on the reader, succeeds brilliantly.” Most reviews were far more appreciative.

Just a few weeks after the book debuted, columnist Walter Winchell reported, in June 1959: “Alf Hitchcock is very mysterious about his next movie. I hear it’ll be based on Robert Bloch’s suspense novel ‘Pyscho.’”

Who knew Walter Winchell called Alfred Hitchcock “Alf?”

By December 1959, Hitchcock – famously using the low-budget crew and production standards of his “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” TV show – was already shooting and newspapers were reporting the cast included Tony Perkins, Vera Miles and John Gavin, “with Janet Leigh in a special guest star role.”

Uh, spoilers, Cincinnati Post editors of 1959.

The Hitchcock film really doesn’t need to be broken down here, but when the movie was released in the summer of 1960, only four newspapers – three in Ed Gein’s home state of Wisconsin and one in Minnesota – noted that the movie and Bloch’s book were based on the Gein case.

Hitchcock went out of his way to poo-poo the connection in an article in the Minneapolis Star-Tribune. “There is only the very slenderest thread of connection,” Hitchcock is quoted as saying. “Bloch knew about the Gein case, but that’s all. He didn’t get any ideas from it.”

Sure, Alf. Sure.

Cashing in on the horror

After “Psycho” told the Ed Gein story through its own particular lens, other films borrowed liberally from his story. How many times have we seen young protagonists stumble onto remote houses decorated with bones and suspiciously sourced lampshades? But the 1974 Tobe Hooper masterpiece “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” is probably the single best film besides “Psycho” to tell Eddie’s story.

And if you’ve never considered Hooper’s film to be a masterpiece, you and I will part ways at the fibula in the road. Because just as “Psycho” is a masterpiece, so is the initial “Chainsaw.” It is a movie where unrelenting dread is slowly replaced by unrelenting horror. A group of young travelers find themselves stranded in a Texas backwater and explore a foreboding house. One by one, the horrific family that calls the house home is revealed. The aforementioned Leatherface is perhaps the most frightening, but that’s mostly because of the mask of roughly stitched human skin, his blood-smeared slaughterhouse apron, his inexorable pursuit and, of course, that roaring chainsaw.

As restrained as “Psycho” is, with just that black-and-white swirl of “blood” going down the shower drain, “Chainsaw” is, improbably, restrained too. In the mind’s eye of moviegoers, Hooper showed a lot more blood than he really did. There’s violence aplenty, of course, of the “hang someone on a meat hook” variety. But the explicit piercing and rending of flesh that viewers experienced with “Chainsaw” was mostly in their imaginations. Mostly.

There are reboots and remakes and rip-offs of these two pinnacles of Ed Gein fictionalizations, and many, many films that play upon our collective mind’s eye memories of those films. But there’s no equal.

There’s also no end to horror fiction stories that owe at least a debt for inspiration to Bloch’s “Psycho,” but there are a couple of cool graphic-industry interpretations. The most recent is “Did You Hear What Eddie Gein Done?” a collaboration of longtime Gein chronicler Schechter, who wrote “Deviant,” and beloved artist and graphic story creator Eric Powell (“The Goon”). The book published in 2021 after a successful Kickstarter campaign.

For graphic – no pun intended – versions of Gein’s twisted tale, I’m partial to an issue of the underground comic “Weird Trips,” which in its second issue, from 1978, presented a cover showcasing Eddie’s story with a decided EC Comics flavor. The Kitchen Sink Press publication could be found on or under a lot of tables in 1980s comic book conventions, which is where I found the two copies I had in my possession for decades. (And still might, although at this moment they can’t be found.)

“Weird Trips” looked like a comic – and that cover art was phenomenal – but Gein’s story inside is told through text called “Ed Gein and the Left Hand of God.” The story was illustrated by drawings and photos of Gein and, inevitably, the sideshow exhibit of Eddie’s car that traveled around the Midwest for a few years after the gruesome story broke, discretely covered in a tent that was festooned with screaming signage.

“REMEMBER ED GEIN OF PLANFIELD, WISCONSIN” the top sign on the tent read. ‘SEE HIS GRAVE-ROBBING AND MURDER CAR. $1,000 REWARD IF NOT TRUE.”

“LOOK SEE THE CAR THAT HAULED THE DEAD FROM THEIR GRAVES,” read a sign on the side of the tent.

It was not a subtle approach to showcasing the handiwork of a notorious murderer. But it would not be the last time other people made money from the horrifying story of Eddie Gein.