The heist is one of my all-time favorite plot devices, familiar and yet constantly open to reinvention. There are so many scenes we expect to see: a master thief taking on a last job, often reluctantly; the assembly of a team of criminals, each with one specific but impressive skill; the planning of the job complete with a visualization of everything going right, even though we know it won’t; the last-minute betrayal that upends everything and tests the moral character of some member of the crew. The pleasure of a good heist comes not from inventing new scenes but from employing these expected ones well: heist fans want to see an interesting crew with impressive abilities and a gift for sharp banter pull off an impossible crime, all preferably delivered with style.

My speculative novel Appleseed takes place over a thousand years spread across three timelines, including one set at the end of the 21st century, in a disintegrating United States suffering from political disarray and environmental collapse. Much of the western U.S. is administered by Earthtrust, a company who among much else controls the global food supply, and who is planning to unilaterally act to geoengineer the stratosphere. In early drafts, I knew the plot involved a resistance group’s attempt to stop Earthtrust’s plan, but I found I had trouble understanding how to structure the story—until I realized that what my characters were planning was actually a kind of heist: they were trying to reach one particular room, in a hard-to-infiltrate and heavily guarded compound, not to steal not money or jewels or art but the future.

Below are some of the heist-inflected stories I love from in SFF and speculative literature, including a couple classic favorites, some more contemporary fare, and one famous novel I’d forgotten had a heist element before I started compiling this list. One of the interesting things about both science fiction and fantasy novels is that they frequently use a second genre to move the reader through their worldbuilding: in this case, it’s the heist, the caper, and the con, some of the most enduring and enjoyable plots you might ever hope to make your own.

Neuromancer by William Gibson

Long before I read Gibson’s debut novel, I was already in love with its perfect opening sentence: “The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.” That image might no longer work on younger readers or anyone else who grew up after television static, since a dead channel on a modern TV is often a flat blue; something similar happened to the worldbuilding of Neuromancer, in which Gibson invented the idea of cyberspace and a world of hackers by imagining a future that in 2021 reads as simultaneously prophetic and alternate-earth anachronistic. With an AI construct secretly pulling the strings to organize a heist in outer space, a crew that includes the unforgettably cybernetically-enhanced street samurai Molly Millions, and the blackmailed master hacker Case working with a computer “deck” many times the size of your much more powerful cell phone, the gaps between our future and that of Neuromancer only makes the novel thrilling in a different: it’s pure style, end to end, and if we didn’t end up with the exact world Gibson predicted—which he wouldn’t have wanted us too anyway—it’s at least a great place to commit a crime.

Steal the Sky by Megan O’ Keefe

O’Keefe’s Detan Honding is an excellent example of a noble thief, a con artist fallen out of favor with highborn society, armed with the cleverness and know-how to succeed in every social sphere he enters. In the desert city of Aransa, Detan sets out to steal a massive airship belonging to Thratia “Throatslitter” Ganal, an exiled war criminal who’s attempting to take over Aransa’s government, only to find the job complicated by his run-ins with Pelkaia, an illusionist shapeshifter (called a doppel in derogatory local slang) who’s on a self-appointed mission of murderous revenge. The heist plot and the revenge plot continually intersect and complicate each other as loyalties—and identities—get harder to trust. It’s a smart, fast-paced story set in an interesting world, with O’Keefe building her plot around the implications of a magic-based economy dependent on colonialist oppression and exploitation—and ripe for a revolution.

Consider Phlebas by Iain M. Banks

In one of the early set pieces of Consider Phlebas, Horza is rescued/captured by the pirate crew of the Clear Air Turbulence (one of Banks’ fantastically named Culture ships), who are on their way to the planet Marjoin to rob the Temple of Light, a target described by the ship’s captain as easy in, easy out: “According to him,” one pirate says, “it’s full of priests and treasure; we shoot the former and grab the latter.” It’s a simple plan, but even the best-laid plans usually go sideways in heist narratives, and this one is no different: the Marjoin monks turn out to be heavily armed, and their temple is a trap made entirely of reflective surfaces that bounce the pirates’ lasers back at them—which means the pirates get to do very little pillaging and a lot of running for their lives.

The Quantum Thief by Hannu Rajaniemi

The opening of Rajaniemi’s The Quantum Thief employs two incredible set pieces and some of the fastest-paced high-concept worldbuilding I’ve seen to reinvigorate one of my favorite heist narrative tropes: the springing of a master thief from prison, with the aim of blackmailing him into one more job. In this case, it’s Jean le Flambeur who gets jailbroken—or at least it’s one of the many fractal copies of him imprisoned by the Archons, immortal AI minds running an endless game of the Prisoner’s Dilemma on their inmates. And that’s just the first two chapters. Soon all le Flambeur and his rescuer/captor/employer Mieli (and her sentient spaceship) land on Mars to infiltrate its encrypted privacy society, where they steal, among other things, people’s faces, their memories, and at least one minute of Time itself, all to get one step closer to the real job they’ve come to Mars to pull.

Provenance by Ann Leckie

Like The Quantum Thief, Leckie’s Provenance opens with a jailbreak. This time, the spectacularly named Ingray Aughskold frees the equally well-named thief Pahlad Budrakin from the prison planet Compassionate Removal, in order to find a series of ancient artifacts Aughskold hopes will help her defeat her brother’s bid to become their adopted mother’s heir. Set in the same world as Leckie’s Imperial Radch trilogy, it’s a perhaps smaller-scale affair—it’s at least not narrated by a vengeful former AI of a galaxy-conquering spaceship, as Ancillary Justice and its sequels were—but it’s equally as smart and exciting, with Leckie expanding on her ideas about empire, history, class, and personal identity throughout Ingray and Pahlad’s attempts to secure the Budrakin vestiges before anyone else can claim them and use them for their own ends.

The Lies of Locke Lamora by Scott Lynch

Locke Lamora’s Gentlemen Bastards are a fantastic crew of orphans tutored in the ways of deception and disguise before being set loose on the fantastical city of Camorr to steal from the rich and powerful. For years, they do absolutely nothing with the money, leaving the tens of thousands of coins they’ve stolen in a vault to do little more than keep score. As the novel opens, the Gentlemen Bastards begin their biggest grift yet, concocting complex identities, donning a series of intricate disguises, and generally scamming everyone they meet: “We’re a different sort of thief,” one character explains. “Deception and misdirection are our tools. We don’t believe in hard work when a false face and a good line of bullshit can do so much more.” As their con unfolds, their drawn into a complex plot threatening to overthrow the Secret Peace between their city’s nobles and the criminal underworld, a danger they can’t buy their way out of, no matter how much coin they have stashed. Lynch’s witty, propulsive dialogue is an absolute highlight here: it’s been a long time since I laughed aloud as much as I did reading this.

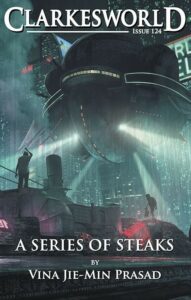

“A Series of Steaks” by Vina Jie-Min Prasad

Not every crime requires an entire novel to unfold, but a good rule of thumb is that the shorter the telling, the more the writer has to focus on a smaller subset of their genre’s component parts: a particular type of scene, or a particular character archetype, for instance. In Prasad’s novelette “A Series of Sneaks,” set in a futuristic Nanjing, Helena Li Yuanhui is a forger, one of the more frequent skills a heist team member might have—but in this case she’s an expert forger of bioprinted beef, trying to lay low by never being too ambitious, despite her obvious skill. Like so many other master criminals before her, Helena is blackmailed into taking on a particularly difficult job, one she can’t possibly escape—but that doesn’t mean she can’t complete it in her own way, pulling off the scheme, completing her contract, and still seeking revenge on the criminal who’s pressured her into using her skills on his behalf.

The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

Given the epic that followed in The Lord of the Rings, it’s easy to forget the much humbler adventure of The Hobbit, which begins with a classic heist setup: an unlikely burglar is hired to accompany an organization (here, a loose family of dwarves) deprived by someone more powerful of their rightful property, with the aim of stealing it back from the original thief (er, dragon). Along the way, Bilbo Baggins, our reluctant and perhaps overly polite burglar—”You have nice manners for a thief and a liar,” the dragon tells him—not only figures out the trick to getting the dragon’s horde but steals the One Ring (not yet called any such thing) from Gollum, using two of the finest tools anyone can bring to a heist: unexpected cleverness and an unassuming appearance.

***