“The city is strong in the memory, no matter how much it decays and gives way to the sea.”

–Elaine Perry, 1990

Since I’ve started writing about out-of-print and “lost” Black authors, I occasionally get suggestions from writer-friends who turn me on to their favorite neglected authors. When I was writing The Blacklist column for Catapult, journalist Ericka Blount Danois schooled me on the Harlem/Brooklyn teen novels of Rosa Guy while respected Miles Davis biographer Quincy Troupe taught me much about the literary life and brutal death of surreal fictionist Henry Dumas. Most recently I received a note from respected memoirist Bridgett M. Davis (The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life in the Detroit Numbers, 2019) inquiring if I’d ever read Another Present Era (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) by Elaine Perry.

Published in 1990 when Perry was 30-years-old, I had never heard of the book or its writer. “It’s beautiful,” Davis’ note read. “It’s dystopian and futuristic at the same time.” As a fan of “dystopian, futuristic” fiction, I thought it was odd that I’d never come across Perry’s book. While I was a reader of Octavia Butler’s writings, it was cool to find out that she, contrary to the beliefs of many, wasn’t the only Black woman writing speculative fiction during that era.

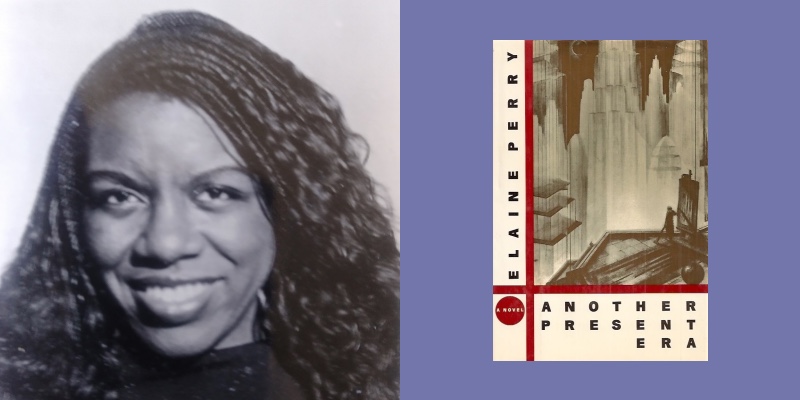

Another Present Era touches on many of the same subjects (global warming, corporate greed, racism and disease) as Butler’s more well-known Parable of Sower, but that book wasn’t published until three years later. After ordering the book from eBay, I did an internet search on Perry, but surprisingly I couldn’t find any of her work online. I did see a cranky novel review of Another Present Era from Kirkus and a smiling photograph of Perry, alongside a short bio, on the book’s Goodreads page.

“Elaine Perry is an American author. Her first novel, Another Present Era, was…a 1990 Booklist Editors’ Choice: Adult Books, Arts & Literature. She also writes poetry and short stories and has taught poetry and fiction at the Oberlin College Creative Writing Program.” There was also a New York magazine profile written by Kelli Pryor from the August 13, 1990 issue titled “Apocalypse Now” that gave a bit of background on the Lima, Ohio native who was born and raised on “the Black side of town.”

Pryor wrote that the author had been “a timid child who was often teased about being brainy and overweight, Perry spent hours in her room, reading encyclopedias and dictionaries. And when she ended up at a predominantly white school she used her abstract paintings as a buffer against other people.” Perry moved to New York in 1981 two days after graduating from college. 1980s NYC, with its high crime rate, urban bleakness and the introduction of crack, was just as rough as it was in the 1970s. However it was still an exciting city that was creatively stimulating for aspiring visual artists, filmmakers, musicians and writers.

Three years after arriving, she got a job at Ogilvy & Mather (where writer Don DeLillo once worked) answering phones for “eight stereotypical yuppies.” It was while working for the advertising, marketing, and public relations agency that she switched from writing poetry to prose. “It was easier to write fiction in that environment,” Perry stated in 1990. I assume that Another Present Era began there and, by the end of the decade, was finished. Though I’m not certain what the title means, Another Present Era shares a name with a 1972 prog rock-jazz fusion-folk album by Oregon.

The cover of Another Present Era is classically designed and features a vintage drawing by futurist illustrator and architect Hugh Ferris. Taken from Ferris’ 1929 classic The Metropolis of Tomorrow the image is a charcoal drawing of a painter standing on a rooftop in Manhattan capturing skyscrapers on canvas. Ferris’ work for that project was influenced by the cityscapes in Fritz Lang’s masterwork Metropolis (1927) and both men’s work inspired production designers Syd Mead (Blade Runner, 1982) and Anton Furst (Batman, 1989) as well as generations of artists, filmmakers and writers. The picture has a noir sci-fi weirdness that is both retro and ultramodern.

However, the strangest thing about the cover was its absence of blurbs from other writers telling us how “exciting, brilliant and outstanding” the text is; instead we get a few graphs from the first chapter which introduces us to “blond, beautiful, brilliant architect Wanda Higgins Du Bois,” the bi-racial protagonist whose complex life, loves, career, obsessions and family fuels the narrative. “The fog in New York Harbor casts a nebula around the dying city,” reads the jacket copy which is also the opening lines of the book. “Wanda is alone on the fifty-eighth floor of the Savings of America Tower, listening to footsteps. But everyone left hours ago and no ghost could haunt a skyscraper like this, ninety stories of smoke-gray glass and steel. It’s past midnight, she should be alarmed, the financial district isn’t safe after hours.”

Calling Another Present Era experimental or postmodern fiction might be a stretch, but the text is not as invested in plot as it is in the characters and their various dilemmas. There’s no specific A to Z story line as Perry’s moody people navigate through existential angst (both past and present) in various bleak, near death cities that wouldn’t be out of place in a New Wave Science Fiction novel imagined by Samuel R. Delany, J.G. Ballard or Thomas M. Disch. There are also elements of noir, melodrama and tragic romanticism as well as the author’s obvious affection for art, classical symphonies, bohemian lifestyles and urban planning.

Race and racism, color and colorism are prominent in the novel, but we are told early on that Wanda, instead of trying to pass for white, applies the “one drop rule” to herself. A concept developed during slavery when masters often raped their slaves who birthed lighter skinned babies, the rule declared that one drop of Black blood made the offspring just that.

“It still astounded and saddened her that she looked nothing like her mother,” Perry writes. “She frowned at her pale hands…” Further into the book Perry states, “Wanda’s been following the story of a coalition of civil rights and other progressive organizations which is trying to have the concept of race declared unconstitutional.” To distance herself further from the white side of her family, Wanda refuses to use her father’s last name Stoller, choosing instead her mom’s maiden name Du Bois.

Wanda’s pro-Black stance reminds me of the Larry Neal quote, “Without a strong sense of nationalism black people would not survive America. There was no way to survive America fragmented and in general confusion about who we were, and what we wanted.” Of course it doesn’t help that from the time Wanda was a child her father Charles seemed to show nothing but hatred towards her mother Francine, telling co-workers that his wife was dead and beating Wanda if she contradicted him.

Daddy Dearest was in the military and had a rocket scientist father who also might’ve been a Nazi. Charles’ family never accepted “the coloreds,” except his younger sister Tyler (“an environmental lobbyist and the only Stoller whom Wanda has been able to befriend”) is very present in their lives. While all the characters are quite serious, one of the funniest sections involves both race and Tyler, who “has told her (Wanda) stories about these whites researching their roots in the National Archives and finding they’ve got an African-American or two in the family, some becoming so hysterical they have to be carried out by paramedics.”

Wanda, a Harvard graduate, while successful in her architectural career (“She thinks about an arts and cultural center for a site on the Toronto harbor. It’s an international design competition and she dreams of winning…”) and making lots of money at the Architects Consortium (“She and everyone else at the Consortium were too busy with corporate parks and planned communities to pursue visions.”), she numbs herself with excessive drinking that often leads to bad decisions and blackouts.

Considering the small number of Black women architects in New York at any time in history, with Harlem born Norma Merrick Sklarek being the first to get her license in 1954, Perry made a radical decision giving Wanda that profession. Unfortunately, Wanda’s success at work doesn’t spill over into her private life. Wanda’s crazy boyfriend Bradley is another one dropper who “is so light-complexioned that he is often perceived as white, and they are united by their mutual alienation, never completely accepted by either whites or blacks.”

However, Bradley remains passing for white and, though he claims to he wants to out himself as Black to friends and co-workers, he doesn’t. Instead of being truthful, Bradley, who lives on a houseboat docked on 79th Street, is slowly going mad. From the moment we meet him at Wanda’s office, where one minute he’s talking about having her dream house built and the next he sticks a gun in his mouth, he is just not right.

While it’s obvious that the race issue is making Bradley batty, suicidal, paranoid and violent, he is also extremely jealous of Wanda’s rich art speculator “roommate” Werner Schmidt, who is really Sterling Cronheim, a famous Modernist painter who disappeared in Paris when it was occupied by Nazis in 1940. Sterling is an American born in Wisconsin, but having spent so much time in Germany as a young artist, in his old age he reminds me of one of the long-suffering men in Otto Dix paintings or the loner in “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” by Caspar David Friedrich.

Cronheim’s haunting story of life as an artist, photographer, Bauhaus instructor and married bisexual wed to a scientist named Lenore, is a parallel narrative to Wanda’s story. Lenore, much like Bradley, is a nerve wreaking character that demands perfection from her partner, but then cheats on him with various lovers including real-life painter Wassily Kandinsky, a good friend of Cronheim.

There is also her longtime best friend, whom Lenore loves more than anyone. “She will never be without Kally,” Perry writes. “Sterling will understand this, too. It’s not too much to ask of an artist, a fellow freethinker.” While Lenore loves Kally like a sister and (perhaps) as a lover, her relationship/marriage to Sterling always seems on the verge of exploding. As with all the characters, the desire to love is strong, but the will is fragile.

Perry’s adoration for city life (Berlin, Paris, Philadelphia) shines through in the prose, but her real devotion is directed towards New York City. Though the metropolis is falling apart with its blackouts, flooding and marauding gangs, Wanda still loves it. As Kelli Pryor noted, “The New York in her novel seems an unthinkable place to live. Steadily falling acid rain eats away at rotting skyscrapers. Civil-defense Klaxons wail through the night while putrid water engulfs the island. And New Yorkers don’t notice.” Though Wanda, like other wealthy people, has the option of living on a faraway planet (“Leave the planet for good, buy an L-5 condo, her academic adviser told her…But outer space is for the rich, the military, and the global corporations. Just another form of escape.”) she stays on earth.

Pryor believes that the main theme of Another Present Era’s is alienation. “The main character…is mired in her sense of not belonging anywhere,” she writes. But, in my opinion, an equally important theme, as corny as it might sound, is family—both blood relatives and the family we create. Wanda’s connection with her boyfriend might be broken, but she still has a close relationship with her mother and aunties.

Perry is a wonderful stylist, a vivid writer whose prose unspools like a European art film inspired by American pulp fiction with a soundtrack by Tricky working with the Berliner Philharmoniker. The respected Poets & Writers journal called the book “tragic and haunting…exceptional (and) daring,” Another Present Era is also one of more ambitious novels of that decade. Perry writes in a maximalist style that hasn’t been in vogue in years. I enjoy texts that are overflowing with ideas on culture and sex, angst filled meditations and doomed people trying to escape the dark cloud that looms over their heads until their last breath.

After reading Another Present Era, which by today’s standards would be labeled Afrofuturism (standing proudly next to Dhalgren and Kindred) I wanted more of Elaine Perry’s words, but there wasn’t any. “It was Perry’s only novel, which is a bit of a mystery, given her talent,” Bridgett Davis wrote in her note. Indeed, it was mysterious, but a few of my favorite creative visionaries created singular works of greatness (Ephraim Lewis/Skin, Charles Laughton/The Night of the Hunter) that will be remembered by a small group of people for years to come.

Though I questioned “why” Elaine Perry stopped publishing, I know all too well that every writer has their reasons for not doing the expected or simply declining to share their writings with the public. While I was hoping to interview Perry as I’ve done with a few of my subjects, she politely declined. “It is my preference to allow the book to speak for itself,” Perry wrote me in March, 2024. Thankfully Another Present Era has so much to say.

___________________________________

For more on Gonzales’ rediscovered books listen to the On Themes podcast Literary Detectives: https://www.ontheme.show/episodes/literary-detectives