It was night, and darker than I had ever experienced. I was alone and outside, awake at 4am while everyone else slept, the Milky Way a dusty cloud above me and the moon yet to rise. The air was warm that close to the equator, even in the quiet black hours, and I was comfortable in just shorts and a T-shirt. Below the soles of my feet, the deck of the yacht tilted and rolled as kindly winds pushed us on towards our destination; behind me the ocean rushed, churned by the rudders into a creamy, frothy wake. A surfacing dolphin, puffing up a fishy sigh into the night air, was the only sign of life.

We—myself and the five near-strangers who made up the crew of this sailboat—were on our way to the Andaman Islands, a sandy, largely unsettled coconut-palm-strewn archipelago in the eastern Indian Ocean. We had left port, in Phuket, Thailand, two days earlier, and had sailed non-stop ever since, even celebrating Christmas Day at sea. Now I was on solo watch, charged with keeping yacht and crew safe in the night. I checked the instruments, consulted the chart. Two hundred nautical miles down, another 180 to go before landfall. More than four days of travelling, four days of waiting, wondering, daydreaming about what we would find when we finally got there. We had paradise in our sights.

Like many a novelist before me, I drew on my own life experiences when writing my debut novel. Deep Water opens with a naval vessel coming across a yacht in distress. On board are a badly injured man, Jake, and his traumatised wife, Virginie. While the ship’s crew attend to her husband, Captain Danial Tengku begins to question Virginie, who tells him they have come from Amarante, an uninhabited, unspoilt island somewhere in the Indian Ocean, known to only a few and sold as ‘heaven on earth’. The couple had set sail for Amarante full of excitement. But dark secrets surface, and abruptly their dream morphs into nightmare.

In 2009 I was working as a journalist on a newspaper in London and starting to feel ground down by the treadmill and burnt out by life. I had grown up in a landlocked county in the UK, about as far from the sea as you can get in this country, but in my late twenties I discovered sailing and the joy and sense of freedom it brings. As Virginie says in Deep Water: ‘What awe there is in harnessing the wind, in knowing its power and yet still being in control; what freedom in being in command of your own self-contained little world, in tune with the weather, the tides, the phases of the moon.’ Like her, I completely fell for the promise of travel to far-flung, beautiful lands—and so I answered an ad for ‘crew wanted’ on a website, quit my job at the Independent, and bought a one-way ticket to Borneo to live on a boat with a man I’d never met.

On board that boat, I discovered a niche of society I hadn’t encountered before. Known as cruisers, these people live on sailing yachts, seeking an alternative existence, united by the thrill of exploration and a love of self-sufficiency and nature (later, working for sailing magazines, I’d find myself interviewing people exactly like this on a regular basis). And time after time, like so many of us choosing a holiday, seeking a break from life, these sailors are drawn to warm blue waters, soft white sands, and fringing palms.

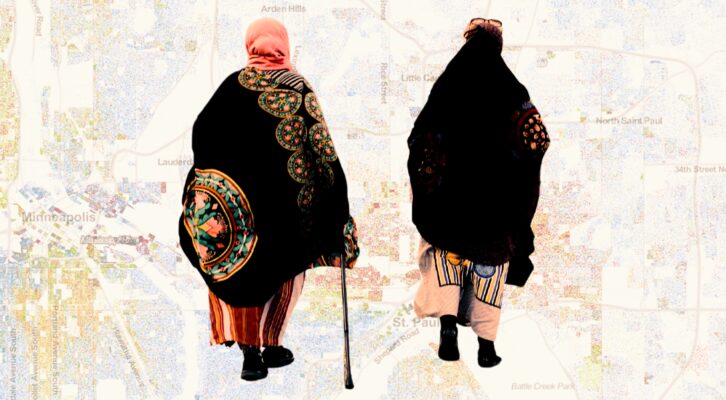

Over the next few years, I lived and worked on five different yachts, exploring South East Asia, the Mediterranean and the Caribbean. I sailed in Malaysia, Thailand, Sri Lanka and across the ocean to Oman. I worked as crew on a superyacht based out of Naples and Sicily. I helped friends take their boat from Kemah, Texas, to Saint Lucia, by way of St Pete, Florida, the Bahamas, Turks and Caicos, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands and the BVIs. I dined on spicy squid, conch and grouper, drank rum punches at sundown, danced by firelight at beach parties. I swam with turtles, walked with wild pygmy elephants, encountered indigenous tribespeople. Every time I packed my bag to move to somewhere new, I’d find inside it a light dusting of sand—lingering traces of any one of a hundred picture-perfect spots that I unwittingly carried with me.

During this time I began to question why it is we are repeatedly drawn to paradise. Beautiful islands have long been a rich source for writers: Robinson Crusoe, Lord of the Flies, The Blue Lagoon, The Beach. What is it about these perfect-seeming places that keeps us coming back? Is it because, as Captain Danial Tengku says in Deep Water, ‘these golden sands are the utopia we’ve been searching for, that we believe they will heal all our wounds’? Life on a boat can be hard, cramped, claustrophobic—conditions that would test even the strongest of relationships (as I learned to my cost). What would happen, I wondered, if you added in clashing personalities, hidden agendas and secret pasts, heat, humidity and the never-ending screech of cicadas? Because even paradise comes with a price.

From all of this emerged Amarante—a mythical lost Indian Ocean island and the setting to Deep Water. This book is about the lure of paradise and escape, but it’s also about the dark side of perfection. No matter how spectacular our surroundings, or how brightly the sun shines, there will always be shadows: in 2011, on that Andaman Islands trip, we were so far from anywhere that we had to ration food and even drinking water. On Ross Island, exploring jungle-tangled ruins, we learned of the place’s horrifying imperial history. I received an email telling me that a sailing friend I’d made in Borneo had died, swept off his boat in a storm, a life gone in a single fateful sweep of a wave. And in a few weeks’ time, when pirates struck, we’d find ourselves in fear of our own lives. I couldn’t un-know these darker elements, so I wrote them into the book. Sunshine and shadow; freedom and captivity; life and death.

Fast forward to 2020. I was finishing writing Deep Water when Covid hit. With the world in lockdown, and a new fear pervading everything, going anywhere became impossible. (The nautical term for this is stormbound—except with the pandemic there was no safe harbour). Creating Virginie and Jake’s adventure was a way for me to travel vicariously while stuck at home—I could remember the way my heels sank into waterlogged sand at the sea’s edge, feel again the hot press of the wind on my face, hear the rustle of palm fronds and the call of the birds overhead. Now, in spring 2022, as the world is slowly opening up, I am dreaming of returning to the bath-warm waters of the Indian Ocean and the sun-drenched shores of the Caribbean Sea. Like so many others, I have paradise in my sights—both real and in the pages of a book.

***