In Springfield, they check into their hotel, an aging Holiday Inn off the interstate. In his room, he calls the executor of the Parker estate, who agrees to meet them at her house in the morning. They walk to a nearby Waffle House and order food, after he gives Hattie her per diem.

In the morning, the executor waits for them at the curb of the Parker home. Hattie wheels the Suburban into the driveway aggressively, grinning, and when they exit the vehicle, the surprise is clear on the executor’s face. Yes, Cromwell thinks. Feds. He wishes he’d worn his sunglasses.

The executor gives a nervous smile as Cromwell introduces himself and Hattie. Her handshake is light, weak, shrinking. This is a strange job, a job where the government is the client and she doesn’t know exactly how to act.

The woman–Sarah–leads them to the house. The yard is neat, flat. The house itself is old, small, and possessed of a certain dignity that only old and well-maintained homes exhibit. The wrap-around front porch has been painted in the last decade, as well as the façade. The roof is a stylish red metal, a newer sort that Cromwell has noticed even in his neighborhood in Alexandria.

Sarah unlocks the front door and lets them in and begs off for an appointment. Cromwell holds out his hand for the keys and after a moment’s pause and an explanation of the alarm system along with the numeric code, she turns the keys over to him and departs. They enter. It’s warm inside. The foyer smells fresh, and clean. Sarah had informed him in their correspondence that Matilda Parker had died of pancreatic cancer, and was a youthful woman in demeanor and outlook, just turned sixty. She had never wed and had no progeny—the last of Harlan Parker’s line. But Cromwell isn’t concerned with the Parker descendant; the woman who died does not interest him in the slightest. It is her ancestor Cromwell’s after.

“What do you bet that if she had a HD television, it’s already gone?” Hattie asks him. They’ve made assays of bequeathed estates before, a handful of times, and there is always something missing once they arrive. A television, a radio or phone, a blank and unweathered patch on a wall. Jewelry, money, pharmaceuticals. Cromwell and Hattie are never the first on-site, and invariably, the baser aspects of human nature become manifest.

He doesn’t take the bet.

Hattie sets up her camera and takes three-hundred-and-sixty-degree photographs of each room, moving from the foyer inward. One of her innovations, a photographic record of estates, has proven invaluable when cataloging. Hattie even promises, if they allot her the money for more gear, she can create a virtual reality record of estates, though Cromwell thinks that a bit excessive.

Cromwell wanders through the house. He finds a small downstairs library full of Grisham, Patterson, Evanovich, Connolly hardbacks, some leather-bound classics—Dickens, Faulkner, Hemingway, Maugham, Mitchell, Ruark, Steinbeck—and a nice set of encyclopedias. I thought the internet killed the encyclopedia business, Cromwell thinks. But those look brand new. He opens cabinets, bemused, looking for anything that might be related to Harlan Parker. In a living area, with a bare space on the wall where some sort of HD television used to be—Hattie will be pleased her low opinion of humanity has been confirmed once more—he finds what, when he was a child, his parents would have called a hi-fi cabinet. A long credenza-like bit of furniture, bracketed at the ends with tweed speakers, with a turntable seated in the center of the lush-stained wood, a long stack of vinyl stored beneath. He flips on the power switch, and the console lights up in lovely 70s design user interface—glowing radio tuner, shining indicators for volume and record speeds. The speakers buzz slightly then subside. He turns it back off, extinguishing the lights. Squatting, he riffles through the vinyl, looking for anything interesting, either personal or professional, but finds neither. He stands, dusts his pants and moves on.

In the master bedroom, he stops. It’s here he feels the weight of the house, its history. A simple enough room, queen bed with a lush, puffy comforter, bedside with elegant if not expensive lamps, a comfy divan in the spill of light from the windows that at Cromwell’s house would probably be strewn with laundry but here is empty. It would be empty now at his home too, he realizes. Even a thousand miles away, he can feel it. That thin connection: a breach, an expansion, like gold beat into airy thinness. Mourning. His house stands empty and cold and silent and that’s something he’ll never be able to surmount. He feels as though he’s shrinking, collapsing under the weight of Maizie and Michael’s deaths.

And the guilt that comes in the shape of a nude woman in a hotel room.

The closet is full of a woman’s clothing, from tee shirts to formal wear, coats and sweaters, slacks and skirts and long dresses. In the chest of drawers, underwear and socks, night clothes and scarves. On the carpeting, he sees the vacuum marks. A sense of dislocation. He’s done this before, and recently, the sorting and taxonomy of the belongings of the dead. For Maizie’s things, her sister collected almost everything he had not wanted. And of his son, Michael, all of his things remained. That was a separation Cromwell was not ready to face.

She had lived and died in these rooms, he thinks. The smell of the space is fresh, but there’s a hint of decay underneath. Maybe, when the cancer worsened, they moved her to hospice. Or hospice came here to wait breathlessly for her to die. In the trash, there’s an empty pill bottle. In the bathroom, the medicine cabinet has been emptied. No one has disturbed her jewelry box on the chest of drawers; its insides glint gold and silver. Behind the bathroom door, a robe, a whiff of rosewater.

Eventually, he’ll have to deal with the estate sale planner, to turn all of this, a woman’s life and clothes and house, into money for the Library. For now, he moves on.

The kitchen is plain, if well loved. A cacophony of pans and skillets hang from a suspended cast-iron rack over an island butcher block. Potted herbs crowd the window sill—thyme, oregano, sage. Cromwell plucks a sprig of thyme and rubs it in his hands, letting the smell of spring and warmer times expand in the still space of the kitchen. He closes his eyes, holds his hands to his nose, inhaling deeply. Once when Michael was five, Cromwell remembers, they passed a towering summer bush of rosemary during a walk through the neighborhood and Cromwell plucked a sprig and rubbed it between his palms like a man using a stick to start a fire and then placed his hands under his son’s nose and watched the perception of the scent creep into his boy’s expression, a blooming wonder, followed by joy. Michael held his hand as they walked and kept drawing it to his face, breathing it in. His sweet boy.

Cromwell keeps his eyes closed for a long while. When he opens them, he lets the mangled sprig fall to the floor.

He unlocks the door from the kitchen leading to the back yard. He moves to stand on the grass. Behind the house, a thicket of trees, all denuded of leaves, and beyond, a neighborhood creek. There’s still snow on the ground under the bare branches. In summer, Cromwell thinks, the air would be full of noise—the creak and cascading hiss of foliage swaying in the breeze, crickets, cicadas, cardinal songs, the cries of boys playing Whiffle ball in the street, maybe, or touch football, bright voices calling victory or outrage, dogs barking in the distance, the whir of a leaf blower, the diminishing roar of a plane full of people flying far away.

There’s a separated garage. More than a shed, less than an outbuilding. Cromwell finds the key that opens the side door on the ring he was handed. A newer lawnmower and weed-eater, two brooms, various rakes and hoes, a snarl of bungee cords, empty liquor store boxes, milk crates. A workbench with a toolbox, mason jars full of nails, screws, nuts and bolts, green nylon rope, a glue gun, shears, hedge trimmers. A Subaru station wagon is in the garage, well-maintained but at least twenty years old. His hands find a light switch, illuminating the space. There’s another door, paint scaling in tessellated patterns, leading to what seems to be a back room.

He opens the door, revealing an empty space with an old desk, an office chair ringed in moldering stacks of hand-written sheet music, yellowed and illegible. On the walls, a guitar, a dulcimer, a banjo. All gray, weathered with time and the vagaries of a drafty, uninsulated room. Cromwell takes down the banjo, finds there are no strings, and the fretboard is rough to his touch.

Someone has spent time here, he knows, long stretches of it. Maybe years. But that was many decades before. It has the haunted feel of a living area, forgotten and repurposed to something else.

The desk is empty, covered in dust. He doesn’t trust the chair enough to sit, and it would besmirch his trousers, anyway. The far wall is packed high with old newspapers and the offal of an old house. Broken wicker chairs, empty crates, plastic tubs full of moth-eaten clothes, bags of mulch, empty pots, broken and shadeless lamps.

His phone chirrups. Hanging the banjo back on the wall he shrugs the phone from his pocket and looks at the text—Found smpin. Upstairs.

Phone in hand, he snaps a picture of the bare room and goes back inside.

“Crumb, this is a straight trip,” Hattie says when he finds her upstairs. “Look at this.” She points to a looming armoire of dark-stained wood near flush with the ceiling. Cromwell opens the doors and looks inside. The reek of mothballs overwhelms him. Winter coats spanning decades of styles.

“She didn’t have good fashion sense?” he asks.

“Around back,” she says.

Cromwell moves to the side of the armoire and places his eye to the gap between the dark, massive furniture and the wall. There’s a glint of metal and hinges.

“I was taking three-sixty-degree photographs of these two bedrooms and realized something was off. Looked in the hall for a closet or maybe a door or stairwell to the attic to explain the space between rooms. I’m good with figuring out spaces, you know?” She raps the wall with her knuckle. “There’s a void back there with no entrance.

__________________________________

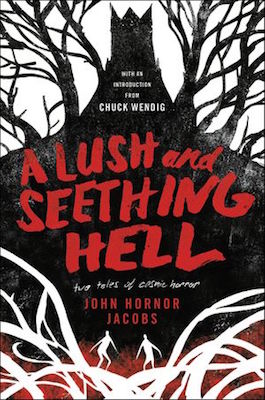

From A Lush and Seething Hell by John Hornor Jacobs. Used with the permission of the publisher, Harper Voyager. Copyright © 2019 by John Hornor Jacobs.