THE INFAMOUS CLUTTER HOME FROM TRUMAN CAPOTE’S CRIME CLASSIC IN COLD BLOOD

Literary tourists have an unprecedented opportunity to vacation in one of the most infamous locations in book publishing history! Now available to rent for the very first time—River Valley Farm—once owned by the Herbert Clutter family, prominently featured in the 1966 literary true crime classic, In Cold Blood, written by renowned author Truman Capote. Stay in this beautifully maintained 5-bedroom, 3-bath, 3600-square-foot classic mid-century farm home in charming Holcomb, Kansas. Marvel at the perfectly maintained kitchen originally designed by Mr. Clutter, gather at the fireplace where the family celebrated Christmas and many family milestones! The 1967 film, In Cold Blood, starring Robert Blake and Scott Wilson, was filmed on this very location as well. Celebrate American literary and cinematic history with a week-long stay (shorter stays not allowed) in this impeccably maintained late ‘40s ranch-style home. No pets, please.

The description of the house on VacationHomes.com grabbed my attention. It was literary serendipity. I had been laboriously scrolling through thumbnail pictures of crappy rental properties across the country for forty-five wasted minutes. All I wanted was a remote little house to finish the book I had been working on for far too many years. I am a full professor in the MFA program at the University of Central Indiana. Four times, my essays have been runner-up selections in the esteemed Best American Essays of the Year anthology. Immodestly, I am a bit of a star in academic circles and in the world of the experimental essay. I have written three books and edited four anthologies.[1] In 2010, my paper, Hybritic Self-Reflection: Retaining Empathy in the Age of the Selfie, created a mega-stir at the annual Associated Writers Conference in Austin, Texas. That same year, I read a portion of my book-in-progress at the Breadloaf Writers’ Conference[2]. Jhumpa Lahiri[3] approached me afterwards and told me she thought it was “dazzling.”

Still, my unfinished book was causing me considerable consternation. For starters, my course load had increased to a ridiculous 2/2. What were the administrators thinking? Do they know who I am?

I was under contract with Dartmouth University Press and the deadline loomed like a Category 5 hurricane spiraling offshore. I was working with legendary editor Gardner Fischbach[4] and there was no room for an extension. If I didn’t turn my collection of connected essays in on time, I would be in breach of contract. The stress was daunting. Things got so bad, my GP acquiesced and generously dispensed a Costco-sized prescription for Clonazepam. Coupled with a single-glass of top-shelf gin every day at 5 pm, and I genuinely felt more relaxed. And this newfound composure afforded me a confidence that, in return, gave me the idea to find a worthy writer’s retreat. So, I went to VH.com and started scrolling through rental properties, hoping one might be conducive to brilliance.

This is when I found the Clutter family farm.

In Cold Blood[5] is an undeniable tour de force of reportage, new journalism, and narrative nonfiction. Granted, it doesn’t do what my peers[6] and I pull off in experimental memoir and the experimental essay but, still, it’s a remarkable book for what it is. And Capote was often in the Clutter house when he worked on the book (and later to visit the film set). I figured, if I needed a place for a week or two, at a goddamned steal no less, I would have a sort of brush with the atoms of literary greatness. It was Truman Capote, for Chrissakes. Besides, I was on sabbatical and on book deadline. So, I clicked “Book It!” and the house was mine for a two-week run. I must say, I was more than a bit elated.

After that, I began researching the house and was intrigued to discover that it was reportedly haunted by the ghost of Nancy Clutter, the sixteen-year-old daughter bound and shot point blank in her upstairs bedroom. Mr. and Mrs. Clutter, along with Nancy and their son Kenyon, were murdered in the house late in the night on November 15, 1959, but, as the paranormal urban legend goes, it was Nancy’s ghost that still wandered the house, restless, agitated, seeking answers to her tragic demise.

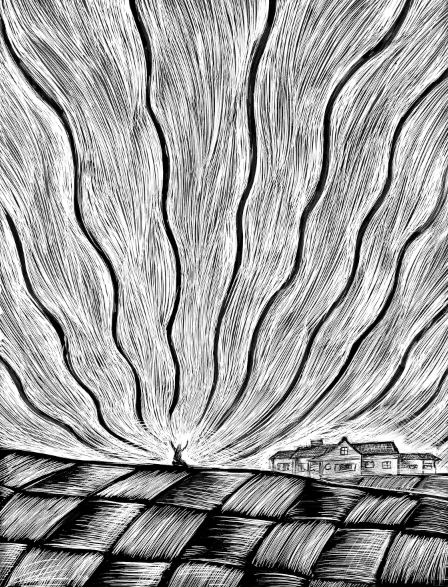

A few weeks later, I was driving up the long, muddy lane to River Valley Farm in my Hyundai Kona. It was late in the day and growing dark, the evening light like an analog film negative. Heavy rains had slowed my drive. The rain had abated, but fog now billowed across the narrow dirt road. Only a few of the Chinese elms lining the straight dirt drive, planted by Herbert Clutter, still survived. Nearly all were dead or dying. The few remaining trees were now gnarled, arthritic, almost prehistoric.

A few weeks later, I was driving up the long, muddy lane to River Valley Farm in my Hyundai Kona. It was late in the day and growing dark, the evening light like an analog film negative. Heavy rains had slowed my drive. The rain had abated, but fog now billowed across the narrow dirt road. Only a few of the Chinese elms lining the straight dirt drive, planted by Herbert Clutter, still survived. Nearly all were dead or dying. The few remaining trees were now gnarled, arthritic, almost prehistoric.

Then I saw it to my right, through the opera house curtains of mist and darkness—River Valley Farm. The infamous Clutter family home.

The house, a 1948 two-story frame and brick affair, reposed on a large expanse of Bermuda grass. There were two adjacent corrugated steel barn-like buildings (as well as a number of old farm vehicles and dilapidated automobiles[7]), but the house was what really took my attention. It looked nearly identical to the old photos I had seen; exactly the way it looked in the 1967 film. Capote had been here, as had actor Robert Blake who played Perry Smith, one of the two murderers. As I drove up, it was not lost on me that Blake himself was tried and acquitted of the 2005 murder of his wife. I thought about Philip Seymour Hoffman, who played Capote in the 2005 film, Capote. Hoffman won an Oscar for it, but then died of a drug overdose less than ten years later. As I parked my car I also knew, through my fastidious research, that the Clutter home only had three owners since the murders and one of them had committed suicide—albeit not in the house, thank God.

Adding to this mounting morass, Capote long maintained that writing his book led to his complete unraveling, to his downward spiral into alcoholism and drug use. While In Cold Blood made him one of the most famous authors in America, and rich, he never finished another book.[8]

I turned the engine off, doused the headlights, and pondered if the Clutter house was, perhaps, cursed.

The rental agency left the front door light on for me. They had informed me by email that the house key was under the black rubber door mat, kindly labelled “Welcome!” As I fumbled with the key, I heard the distant wail of a train and wondered if it was “The Chief,” “The Super Chief,” or “The El Capitan,” as Capote had described the passenger locomotive wraiths roaring by in the rural night.

I unlocked the front door and stepped inside through a small vestibule and into the living room. Immediately, I thought of a famous photo of Truman Capote standing in this very space, the very space I was now in. In the photograph, he is near the painted white fireplace mantle, contemplative, wearing an olive trench coat, hands deep in its pockets. I must admit, it was overwhelming. I was in a mythic setting, little changed in over half-a-century.

I unloaded my car: my luggage, a box of books[9], my laptop, and groceries. I had also stocked up on several bottles of Tanqueray Ten gin. It was now completely dark, an early autumn night fallen upon far western Kansas. Once everything was inside, I closed the door and felt unusually alone, in this house with its horrors; this house more than a mile outside the outskirts of tiny Holcomb; on a large parcel of shadowy farmland, at the far end of nowhere. It felt like I was at the end of the earth, at the end of the spiral arm of the galaxy.

Then, a noise. It came from the basement. A sharp clicking and a small expulsion of air. I hoped it was just the water heater igniting, but I was on edge. The basement was where Herbert Clutter and his son Kenyon were tied up and killed.

I foraged through my Dopp kit for my anti-anxiety meds. In the kitchen I poured a glass of booze and popped a pill. The kitchen was like travelling in the Wayback Machine. The white cabinets and blue and white tile counter tops were all original, designed by Herbert Clutter.[10] I filled a highball glass with ice and a generous portion of gin. I knew that in ten or so minutes, the edge would be gone.

A loud noise upstairs. Something had fallen. I’ll admit, at this point, I was shaking. But I breathed. What did I expect? I came to this house, knowing its violent past, even hoping against my own common sense and total disbelief for some sort of paranormal encounter.

I started a self-guided tour of the house.

The master bedroom was on the first floor, along with the dining room and the office.[11] I decided I wasn’t going to go down to the basement. There’s just something about being all alone in a house (especially this house) and going to the basement at night. No, that could wait until sun up.

I went upstairs, acutely aware that Smith and Hickock had ascended these very glossy oak steps to murder Mrs. Clutter and young Nancy, the darling of Holcomb. I discovered what had caused the noise—an upstairs window was left open a few inches, the cream lace curtains shifting in the night breeze, ghostlike. The wind apparently knocked a small vase of dried flowers off a display table and it crashed to the floor.

No ghosts, I thought. Just the wind.

Breathe.

I inspected the upstairs. Three more bedrooms, the murder rooms of Mrs. Clutter and Nancy. The four-post beds were both made up, with handmade quilts and frilly pillows. The bedside tables had doilies on them. The décor was precious and elderly, but warm and inviting despite the cloud of tragedy. I thought about where I would sleep in this house. I was unsure.

One thing that was updated—the living room had a large, high-definition flat screen television with a satellite hook-up. I sat down on the floral print sofa, glass of Tanqueray Ten in hand, and turned it on.

The TV came to life.

Channel 2: The first image was of a man, eyes wide open, lying on sofa, a bullet hole in his forehead. It was one of those 48 Hours unsolved crime programs.

I sipped my gin and pressed the arrow up button on the remote control.

Channel 3: An image of dozens of Syrian rebels, lying in heaps on top of one another, faces contorted because of a nerve gas attack.

I flipped the channel again.

Channel 4: Michael Myers crashed through the louvered closet door, kitchen knife in hand as Jamie Lee Curtis cowered in the corner.

Channel 5: Closeup of a screaming baboon, screeching, baring its teeth.

I turned the television off and finished my drink. I poured another.

There was one more oddity of modern convenience in this time-capsule domicile—internet service and two surprisingly thunderous wi-fi speakers. The owners had taken care to add a few amenities for renters. So nice. I pulled out my laptop and streamed the Rolling Stones. The anxiety meds had kicked in, and emboldened by the gin, I was feeling better. More relaxed. Fuck the ghosts and the noises and the past. I was here to write, dammit. I was going to finish what I already knew would be my magnum opus.

I cranked the music up. I blasted the Stones for a long time and continued to drink. What the hell? It was my first night there. It was getting late and the writing could wait until morning. Mick Jagger called into the night:

Kids are different today

I hear ev’ry mother say

Mother needs something today to calm her down

And though she’s not really ill

There’s a little yellow pill…

WATCH A BOOK TRAILER HIGHLIGHTING THE EXQUISITE ILLUSTRATIONS

As I stood in the living room looking out the picture window, drinking, reveling in this moment of total freedom, out in the inky darkness, headlights approached up the long drive.

What the hell? It was eleven at night.[12]

The lights bucketed up and down as the car dipped and lurched up the bumpy dirt road. My first thought was of Smith and Hickock coming up the driveway in their black Chevrolet in 1959. Who the hell was this? I am vehemently against guns, but at that moment, I wished I had one. Oak Lane runs parallel to the front of the house, then begins to snake towards it. As the car wheeled around, headlights played through the windows of the Clutter home, blinding me briefly, casting distended shadows across the living room.

Then the headlights went dark.

I heard a car door slam shut, soon followed by footsteps up the walkway and the two concrete stairs to the front door.

A knock. I was fucking mortified.

The music roared. Mick was now proclaiming:

Pleased to meet you

Hope you guess my name?

I turned the music down.

“Who is it?”

“Holcomb police,” a raspy voice responded beyond the front door.

How could I be sure it was really the police? Here’s the most absurd thing: I’m in a house where four people had been murdered and there wasn’t a fucking peephole in the front door? Had no one thought to install this simple mechanism of modernity?

“Is there a problem?” I responded. I was feeling loopy on the booze and meds, my cranium now a carnival tilt-a-whirl.

“Is everything okay in there?”

“Yes. Why?”

“Do you mind opening up the door?”

What the fuck? Really?

“Sir, excuse me, you understand that seems reckless to just open the door to a stranger. I’m renting this home.”

“I’m Officer Dunphy, Holcomb, Kansas P.D. This house was vacant for two months. I noticed the lights were all on and wanted to make sure everything was in order.”

Oh, what the hell? I reached to unlock the door. Copycat murders happen, but I was done with this little game. If it was a cop, I’d done nothing wrong. If it was some killer emulating Hickock and Smith, well, fuck it. He would have to face me, at this point an angry and utterly inebriated Fulbright scholar.

I opened the door.

Officer Dunphy was young, with a military air. He was over six feet tall, muscular as a monster truck, topped with a crew cut. He wore a dark blue uniform, a silver badge, and a chest radio.

“Evening,” he said.

“May I help you?”

“Sir, do you have proof you’re a guest here? Holcomb is a small town and we had no notice the home was available to rent.”

“I have an email confirmation,” I said. “If you look at VH.com you’ll see the house is available for rental.”

“VH.com?”

“Vacation Homes dot com.”

He looked over my shoulder.

“Mind if I step in, sir?”

I stepped aside and he entered and glanced around. The Stones still played, albeit at a much lower volume.

“I have the owner’s phone number, if you’d like to call her,” I offered. “She can confirm everything.”

“How long are you staying here?”

“Two weeks.”

“Why would you rent this house? Don’t you know about it? Or does that sort of thing interest you?”

“I’m a writer, officer. This house has a tragic past, but it’s a literary one.” I realized I was slurring my words. I usually didn’t drink more than one glass of gin with the anxiety meds but I had violated my own rule and was feeling the effects.

Officer Dunphy walked in to the living room, looking around curiously.

“You write books?”

“Yes.”

“Do people still read those?”[13] he asked, moving into the dining room. “I’ve never actually been inside this place. This is where it all happened.”

I nodded. “That’s why I decided to rent it.”

I opened the rental contract up on my laptop and tried to show him.

“Here’s my agreement,” I said, balancing the computer in my hand. He didn’t even look at the screen.

“The owners of this place are really private,” he said, as he walked into the kitchen, looking at every detail. “Gawkers come here to take pictures. The owners put up no trespassing signs, they would even fire guns into the sky when cars drove up, if you can believe that, to scare off strangers.”

He ran his hand along the countertop.

“Mind if I have a peek in the basement?” he said, finally looking at me. “I’d love to see it.”

“Sure.”

He opened a door, flicked a light switch on, and descended the staircase. I wasn’t going to investigate it earlier, but now accompanied by Officer Dunphy, I was no longer as intimidated.

We reached the bottom of the steps. The walls were cinderblock, there was a forced air furnace, a water heater, and in the corner, a few cardboard boxes marked “X-Mas Ornaments,” possessions of the current landlords. Next to these was a large plastic Santa Claus lawn figure, the kind that lights up. It was standing against the wall, looking right at me, right through me.

Officer Dunphy walked around the basement with purpose. He inspected one of the walls.

“Huh,” he said.

“What?”

“I read on the internet there was a blood stain down here. It happened when Perry Smith stabbed and then shot Mr. Clutter.[14] The stain is near where his body was found. And here it is. I thought it was some urban legend.”

I walked over and looked at the reddish-brown stain on the wall. I suddenly felt sick to my stomach, not so much by the apparent blood, but the mix of alcohol and drugs in my system, and a sense, for the first time, of how violated the Clutter family was. It was horrendous and I was contributing to it.

I vomited. It splattered over the concrete floor.

Officer Dunphy stepped away from me. “What the fuck? Are you okay?”

I wiped my mouth with my shirt sleeve. “Yes. Just feeling a little overwhelmed.”

“Looks like you’ve been drinking, too. I’ll let you clean your mess up there,” he said, pointing to my puke. “Then you should go to sleep.”

“I guess so.”

“First,” he said, pulling out his cell phone. “Would you mind if I take a few pictures down here? It’s pretty incredible.”

“Whatever you want. I’m going back upstairs.”

I returned to the living room and sat down on the sofa. Officer Dunphy paraded around the house with his cell phone, taking photos of each room like an eager tourist in Hollywood with a map to the homes of the stars. I was feeling sick again and lay down.

“Hey, thanks for letting me see the house,” he said, finally emerging in the living room.

My face was pushed against the cushion of the couch. I couldn’t even get up.

“You don’t want to see my rental agreement? I thought that’s why you came out.”

“No, I believe you. What I can’t believe is that I just toured the Clutter house. It’s incredible. Absolutely incredible!”

He walked to the front door to leave. He turned to face me. “Hope you feel better. You should really lay off the sauce.”

He closed the door behind him and I fell asleep.

I woke the next morning in the same position. I had completely passed out. The skies outside had cleared, and sunlight fell all across River Valley Farm. The land was awesomely flat and went on forever.

My first night had been a fucking abomination. Today would be better. I made coffee, then went to the basement to clean my mess from the night before. I showered, dressed, and dedicated the rest of the morning to writing.

I didn’t write a word. Well, I wrote several paragraphs, but deleted them. They were all shit. I sat there for the entire morning crafting nothing. I made breakfast. Went for a walk across the farm, and tried to write after lunch. More garbage, far beneath my standard.

I drove into town. There was not much to see. Lots of industrial buildings, a concrete plant, tall grain silos, and countless steel storage facilities. A new elementary school. A convenience store. A bank. The police station. A Mexican restaurant. There was no town center, just train tracks cutting the town in half. I saw very few people. It felt soulless. A ghost town.

I drove back towards River Valley Farm, up the gravel drive with the dead trees. I returned to the house with the intent of writing again. This time, what the hell, I poured a drink, despite the previous night.

I sat down in the dining room and worked on an essay that had been vexing me for some time, a prose poem about my chiropractor. For a few hours, I drank and wrote. I was stringing words together that felt good and right. But when you write and you are in the moment, in that groove of mystic meditation, it is virtually impossible to see the proverbial forest through the trees. You can’t be sure if what you are creating is, in fact, any good, and you can only rely on what you are feeling. And I was feeling it, dammit. By the end of the day and a fifth of Tanqueray Ten, I had a complete draft, and I was buzzed and more fearless. I hoped that this night, when the rural land once again surrendered to shadowy underworld, I might encounter the spirit of Nancy Clutter, wandering the house.

I dimmed the lights, listened to the Doors, “The End,” and sat on the sofa, and I drank. My writing was done for the day.

By 9:30, I passed out on the couch, out for the rest of the night.

Next day. Up at dawn. Brewed coffee and reread the 1,500 words I had crafted the previous day.

It was all complete shit.[15]

What was wrong with me? Why the anxiety? What was the hell was going on?

I worked all morning, holding off on the booze. I am, if anything, disciplined at my craft. Philip Lopate once told me that I was “as prolific as a Norway lemming.”

The Clutter house was quiet, remote and lonely. It was the perfect setting to complete my book, yet I was in mental disarray. I was crafting drivel faster than a B-rate Hollywood film studio. What the actual fuck?

So, I opened the gin. I sat down on the sofa and opened a copy of In Cold Blood I had brought along. By page eleven, as I sat there reading and sipping my gin, I was reminded that Herb Clutter, by all accounts a good and generous man to all, including his farmhands, as Capote described him, only had one attribute in others that truly bothered him, a strong disdain for alcohol:

‘Are you a drinking man?’ was the first question he asked a job applicant and even though the fellow gave a negative answer, he still must sign a work contract containing a clause that declared the agreement instantly void if the employee should be discovered “harboring alcohol.”

Days moved by like the swipe of a finger on a smart phone calendar app. I was lost and producing a veritable cesspool of absolute waste. I don’t believe in writer’s block, but I was crippled. My creativity was akin to one of the last few remaining Chinese Oaks that Herb Clutter planted when he had life and time and the world before him.

And then, for him, it vanished by knife and muzzle flash.

Six days of super-glue stagnation and I needed a change. I was also out of booze.

I drove to Holcomb to replenish my gin supply. When Capote came to Kansas to write his book, Finney County was dry. Thank God that had changed.

I stepped into the convenience store, a birdcage bell above the door jingled to mark my entrance. A young woman behind the counter greeted me with an enthusiastic “Hi!”

She wore an acid-washed jean jacket with tassels, nodding her bob of chestnut hair. I had to look at her twice. She had a milk complexion and if Nancy had lived, she would look like this young woman. Almost exactly.

I moved down an aisle towards the booze. Most of the canned goods on the shelves were covered in a fine layer of dust.

I was dismayed to discover the store didn’t carry top shelf gin, only bottom-shelf Carnaby’s London Dry in a plastic bottle. But I grabbed it anyway.

“Is that it?” the young woman asked when I approached the counter.

“Yes, thanks.”

The register pinged as she rang up my gin.

“I haven’t seen you around here before.”

“Just visiting,” I said.

She looked at me. “Where you staying?”

I smiled. “At the old Clutter Farm. It was available to rent.

She cocked her head to the side.

“Oh, I see,” she said at last.

“See?”

“You’re one of them.”

“Who? What do you mean?”

“The people who think the murders are cool. My grandpa and grandma knew the Clutter family. They were friends.”

“I don’t think that. Not at all.”

“Well, it’s sad.”

I pulled out of the parking lot and realized the house was just not doing it for me. Holcomb, in fact, held little allure other than the history of Capote walking its streets in 1959, taking notes and a few photographs. Most of the locations he noted in his book were now long gone. But he had stayed in nearby Garden City, the town were the Clutters were laid to rest.

The sky was shifting into autumnal variations of flannel greys. I headed to Valley View Cemetery.

I found the graveyard in Garden City, a little over ten minutes from Holcomb. It was larger than Holcomb and a proper city.[16] Thanks to Google maps and findagrave.com, I easily located the family. The internet is a strange amalgam of remarkable convenience and keyhole voyeurism I often have trouble reconciling.

I parked my car.

The sky had darkened as I walked out among the headstones and plastic flower bouquets toward the Clutter family plot. I approached the rose-colored granite. A light rain began to fall, more of a mist than anything.

Herbert Clutter, 1911-1959, next to his beloved wife, Bonnie Mae Clutter, 1914-1959. To the left, Kenyon, 1944-1959, and to the right, Nancy, 1943-1959.

I stood before the headstones. I was now residing in these people’s home, the place Herb Clutter had designed and built with a future in mind. And, now, here I was, yet another stranger in their midst.

“I don’t mean to trespass,” I said, under my breath.

I couldn’t fucking write in that house. I kept drinking and listening to music, my standard jumpstarts, but nary an original word emerged. This book was fucked. The deadline would be blown. Into my second week, I was destitute. I kept hoping in a sick way to encounter the spirit of a murdered teen girl and, instead, the only haunted spirit was my own.

I drank more. And took more pills. Because, why the hell not? It extinguished the flames of failure, at least in the moment. And I produced nothing, I wrote nothing. ln my second week of residency at River Valley Farm, I drank and swallowed anti-anxiety medicine and listened to Johnny Cash sing about not taking your guns to town.

And late one night, a waxing crescent moon bathing the shorn rows of farmland beyond the house, I blasted Black Sabbath and decided to just get completely shit-faced. I was not writing. Clutter Farm residency almost over. Manuscript incomplete.

I went to the basement stairwell, flicked the lights on, and descended the stairs. They had filmed the murder scene for the ’67 film here. The real murders had occurred here. I walked over and looked at the splatter on the wall. I ran my fingers over the cinderblock wall, across the stain.

We do things sometimes without thought, pure animal instinct, no intellect. I ripped my button-down Oxford shirt, blowing the row of buttons. I took my jeans off and my underwear.

I ran upstairs and poured a tall gin and gulped it.

Ozzy wailed: “Oh no no please god no.”

And I opened the front door, stark naked, drunk, head spinning, and I ran. I ran across the dry Bermuda grass. I ran beyond the steel hut farm buildings and the old equipment and the dilapidated cars. I ran, naked, across the clods of earth and the rows of wheat stubble. I ran out into the night, under the sliver of moon, and kept on running.

I don’t know how far I went. I could have run forever.

Finally, I collapsed, in the void of mud and rows of plowed field. I fell to the ground, in that area where Kansans called “out there.” I was naked. Filthy. Arms and legs splayed. Staring at the night sky. I clawed dirt in my hands and cried. I thought of the four shot gun blasts on that November night. I thought of Kenyon and Nancy, Herb and Bonnie.

Mrs. Bonnie Clutter. Capote described her as suffering from depression, from anxiety, from anguish. She had even sought treatment, he wrote. Mrs. Clutter’s mental lapses into mania, Capote said, were her “little spells.”

I saw so clearly now how the Clutter family had been victimized not just that night, but long after it. Capote was a goddam opportunist. He had turned their tragedy into his art. Robert Blake and Scott Wilson and Director Richard Brooks, they shot their film in the house, next to and even on the Clutter furniture. And then another film, Capote, awarding Philip Seymour Hoffman an Oscar.

And finally, the house went up for rent and a sad fucking writer side-saddled alongside the decades of opportunism and abject tragedy.

How many people had profited, marveled, been drawn in by the murder of this midwestern family? How many?

Laying there, out in a dry mud clod field I was having my own little spell.

I stared at the moon and I quivered up at a dark black sky.[17]

[1] I, Brooklyn (Harcourt Brace, 2002), Pastiche (University of Iowa Press, 2004), Flowers of

Ponderance, (University of Texas Press, 2011); Anthologies: The Last American Essay, co-edited with

Carefree Pimpleton (University of Iowa, 2006), The God Colloquy, co-edited with Philip

Lopate (University of Iowa, 2010), New Algorhythms (Wake Forest University, 2015), The Secret Goldfish

(New York University Press, 2017)

[2] Breadloaf is the mother of all writers’ conferences. Held each summer since 1926 outside Middlebury, Vermont. The New Yorker deemed it “the oldest and most prestigious writers’ conference in the country.” Everyone from Toni Morrison to Robert Frost have taught workshops or read their work here. I was quite honored to participate.

[3] It pains me that I even have to footnote this, for fuck’s sake, but for those who do not know, Jhumpa Lahiri is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Interpreter of Maladies, among many others. She also won the National Humanities Award in 2014. It saddens me how ill-read so many Americans are. They can list the entire filmographies of no-talent actors, yet have no clue when it comes to writers or books.

[4] There is no need to explain this man’s credentials. LEGEND.

[5] In Cold Blood was published in 1966 and was instantly hailed a masterpiece by many a critic. It was also immediately controversial. Capote claimed to invent a new form—the “nonfiction novel,” setting out to tell a meticulously reported story utilizing the tools of the fiction writer, i.e.: scene, character, dialogue, point-of-view, etc. He also utilized a simultaneous triple narrative structure. If Capote “invented” anything, he certainly birthed the true crime genre. And this is by no means a slight to the quality of the prose. In Cold Blood is elegant and elegiac, beautifully articulated, while utterly painful in its American Gothic grotesqueness.

[6] When I say “peers,” there really is only a dozen (at best) absolutely exceptional writers of experimental creative nonfiction currently at work in the field today. Most contemporary nonfiction essayists are overly concerned with narrative at the expense of structure and forms such as the lyric, braided, acrostic, or other hybrid essays.

[7] All the cars and farm vehicles out by the two large steel storage structures gave the property a slight Deliverance vibe. It was creepy. I wondered if the house was better maintained, after all, I was paying for it.

[8] I was facing my own brick wall with my current book under contract, well understanding Capote’s crippled creative process. In my life, I have been crippled by my own dark past and it does come in to play into one’s ability to produce art on demand.

[9] I brought a mix of reference books (I still prefer old-fashioned dictionaries over the internet), along with a range of canonical and contemporary works for inspiration. Here is the God’s truth: If you are a writer and you don’t read, you should quit. Now.

[10] Herbert Clutter designed the house in 1948 and built it for $40,000. The home, by farmhouse standards, with two wood-burning fireplaces and 3600-square-feet on two floors (1700 additional square footage in the basement) was roomy and quite modern. Clutter was a fairly prosperous farmer. He was founder of the Kansas Wheat Growers Association, and was appointed by President Eisenhower to the Federal Farm Credit Board in 1953. By all accounts, Herbert Clutter was an outstanding family man and member of the Holcomb community. He was also instrumental in helping to build the Methodist Church in Garden City where the family would later have their funeral service.

[11] SPOILER ALERT: If you have not read In Cold Blood and are unaware of the seemingly motiveless murder of the Clutter family, read no further. The first-floor office belonged to Herb Clutter and was the reason Smith and Hickock came to the house in the first place. Hickock, a convicted felon, had been told by a former cellmate, and former employee on the Clutter farm, that Herb Clutter kept a safe in his office with $10,000 cash inside. This is what brought Smith and Hickock up the long drive to the Clutter home that night. There was no safe, no cash, Smith and Hickock only left with $50, a pair of binoculars, and a transistor radio after having murdered the four members of the Clutter family. But the deaths of this family, because of Capote’s book, continue to captivate people. Two older Clutter daughters, no longer living at home at the time, survive to this day but do not grant interviews.

[12] Reading up on the house before my arrival, I learned that gawkers, gapers, and the prurient frequently drove up Oak Lane, the long dirt lane towards the Clutter farm, for a glimpse of the infamous home. People had flown drones over and filmed it. There seemed to be no end to the curiosity surrounding the Clutter family murder, and this is one of the reasons the current owners decided to rent the house out on VacationHomes.com. I hoped that my own visitor was just another of the curious throng of inquisitors.

[13] This is what is wrong with America.

[14] The murder scene for the 1967 movie was also filmed in the basement.

[15] How does a writer know when his work is sub-standard? Can this level of immediate objectivity be taught? Reading is really the key, distilling the words of so many before us, subconsciously learning from the masters until their brilliance becomes ours. I plan on penning a book in the near future on the writing process.

[16] Holcomb has a modest population of just around 2,000.

[17] Editor’s note: Near the end of his two-week residency in the Clutter family home, where this essay concludes, Alex Langman suffered an acute nervous breakdown. He was hospitalized at a Garden City psychiatric facility where he is still undergoing treatment. “Little Spells,” the title essay in this collection, is his first piece of writing, penned while hospitalized, with permission from his doctors. We are hopeful Alex will make a complete recovery.

__________________________________