The sun cut sideways into Massimo Marini’s face, drawing out a blaze of color as it filtered through his brown eyelashes. He was walking with nervous steps down a street flanked by hidden gardens, kept out of sight by thick walls. Petals from the taller branches of the trees behind the walls had fallen onto the street. It was like treading on something that was still alive, a carpet of dying creatures.

It was a drowsy, placid spring afternoon, but the roiling black mass at the edge of his line of sight announced an upheaval. The air crackled with electricity, a contagious force that made the inspector restless.

The entrance to the La Cella art gallery was marked by a brass plaque on the coarse plaster exterior of a building from the 1600s. Reflected on the metal, Massimo’s eyes looked as twisted as his mood. He rolled down his shirtsleeves and put on his jacket before ringing the doorbell. The lock clicked open. He pushed the studded knocker and entered.

The day’s warmth reached no farther than the threshold. The moment he stepped through the door, a wet weight seemed to settle on him. The floor was checkered black and white, and a stairway of veined marble curved upward toward the second floor. Light filtered through some of the high windows onto a chandelier made of Murano glass, launching emerald shimmers into the semi-darkness of the ground floor. There was a smell of lilies in the air. It reminded Massimo of incense, the inside of a gloomy church, endless litanies and the stern look on his father’s face whenever Massimo—then still a child—dared show any sign of boredom.

His head began to pound.

His mobile phone vibrated with an incoming call and in the silence of that solemn place, the sound seemed to belong to another universe.

He took out his phone from his breast pocket. It writhed in his palm like a cold, flat artificial heart, but Massimo knew that on the other end of the line was a real heart in which love wrestled with rage and disappointment and pain. His phone had been ringing with that number for weeks now, often several times a day, relentless.

He ignored the call, his mouth pasty with a sickening mixture of remorse and guilt. He let the call ring out and switched his phone off. Circumventing the marble stairway, he descended a set of wrought-iron steps that spiraled ivy-like into the basement. Muffled voices floated through the gloom. A hallway dimly lit by lamps set into the floor, a door made of pebbled glass and beyond, the gallery.

La Cella, finally. The vaulted ceiling of coarse tiles stood above a smooth slate floor. Along the walls, most of the plaster had been scraped off to reveal the original stonework beneath. Each splash of light fell precisely onto each of the pieces on display, drawing them out like jewels from the shadows. Bronze sculptures, glass vases and dazzlingly colorful abstract paintings were the characters on that spare underground stage.

The inspector followed the murmur of voices to a cluster of people standing in the most spacious room in the gallery. A pair of uniformed policemen stood guard along the edges. Past them, Marini recognized Parisi and de Carli, both in plainclothes. Olive-skinned, muscular Parisi was talking quietly on the phone, while de Carli—as skinny and ungainly as a teenager—watched and occasionally intervened. They had become Marini’s team ever since he had requested a transfer from the city to this small local precinct. He had thought—or at least hoped—that this change in trajectory might be a way to find solace and perhaps start over. He’d ended up finding a whole lot more than he’d expected, but solace remained a fire-breathing chimera that burned him every time he reached out to grasp it.

He walked up to his team.

“What’s going on?” he asked de Carli.

De Carli pulled up his jeans, which had slid down his thighs.

“God knows. They haven’t told us a thing yet. It’s all a big mystery.”

“Then why did you tell me it was urgent?”

Parisi covered the phone with his hand and tilted his chin toward the opposite side of the room.

“Because she needs us. And you.”

Marini’s eyes searched for the person who had made every minute of his life hell over the past few months, but in doing so, had brought him back to life.

At first he only saw her feet, glimpsed between the legs of two officers. She was wearing wedge trainers and kept shifting her weight from one side to the other; every now and then she stood on the balls of her feet to give her legs a rest.

She’s tired, he thought. And although he had no idea why the team had been dispatched to La Cella, he knew she would be the last person to leave that day.

Then the two officers moved and he could finally see the rest of her, standing between a bronze sculpture of a half-liquefied heart and an installation of Perspex wings hanging from the ceiling. Heart and soul, just like her.

And determination, a vitality that sometimes threatened to crush those closest to her but always managed, at the very last moment, to pick them up and push them beyond what they thought possible.

It also happened that she was a bit of a bitch.

There was a raggedness to her appearance that had less to do with her age—sixty—than with some inner torment that Massimo could not yet name and that only seemed to find release in the notebook she kept permanently clasped in her hands, filling it with frenzied scrawls at every opportunity.

He walked up to her and noticed the single blink with which she registered his arrival. She didn’t even turn around. She was holding one of the temples of her reading glasses between her lips and chewing nervously on a sweet.

“I hope it’s sugar-free,” he said.

She finally looked at him, though for barely a second.

“And that is your business because . . . ?”

Her voice was hoarse and dry, and leavened with a note of amusement.

“You’re diabetic, Superintendent. And supposedly a lady, too . . .” he muttered, ignoring the curse that followed.

It was a familiar game they played, one he almost never won.

She stopped gnawing at her glasses.

“Isn’t this supposed to be your day off, Inspector?” she asked, boring into him with those terrible eyes of hers, so adept at seeing well below the surface.

Massimo gave her a half-smile.

“And haven’t you just finished your shift?”

“All this diligence won’t compensate for your recent lapses, Marini.”

Massimo decided to avoid the minefield of a possible response. Already, she appeared to have lost interest in him. He watched her closely, this woman whose head didn’t even reach his chest but who could crush his ego in the blink of an eye. She was almost twice his age, but frequently left him behind, exhausted, well before her own energies were spent. Her manner was often brutal, and her hair, styled in a bob that framed her face, was dyed such an artificial shade of red that it was almost embarrassing. Or at least would have been on anyone but her.

Teresa Battaglia could bark, and there were some who swore they had seen her bite, too—quite literally.

“So? Why are we here? What’s with all the mysteries?” he asked in a bid to draw her back to the hunt—that territory, she could navigate better and faster than anyone else.

Teresa Battaglia was staring straight ahead as if she were looking at someone, her eyes narrowed, black thoughts lodged in her furrowed brow.

“Singular, Inspector, not plural. There’s only ever one mystery.”

Superintendent Battaglia wiped the lenses of her reading glasses, as she did every time she was thinking. She was putting her thoughts in order.

“Why else would we be here, if not to solve the mystery of death?”

***

“Cold case.”

That was how Deputy Public Prosecutor Gardini had described it not even an hour ago when he’d summoned her to La Cella. Two words, followed by something Superintendent Teresa Battaglia had heard him say countless times before: “I want you and your team on this.”

Cold case. Teresa had been relieved to hear that; it meant no killer on the loose to hunt down, no potential further victims to save, no immediate threat. Only the echo of something that had happened long ago and somehow resurfaced now.

She could handle it. She was not going to lose control of this case, and even if she did, there would be no harm done—except perhaps to her ego.

You’re a fool if you think they won’t notice what’s happening to you.

What was happening to her had a name so powerful it could crush her, but Teresa had not retreated from the word on her medical record, had not stepped aside and let it take over her world. Instead, she had locked it away where all our most terrible fears like to settle: in the depths of her soul—and in the diary she always carried with her. Her paper memory.

Massimo Marini was another problem in an already complicated situation. He kept looking at her as if he suspected something, as if he had access to her thoughts. She found it difficult to keep him at arm’s length; in fact, his closeness had started to feel normal, almost welcome, and she had begun to worry that this urge to seek each other out might become a dangerous habit for them both.

Prosecutor Gardini emerged from a room that had been cordoned off. He looked anxious, as always. A lanky man with permanently disheveled hair and a scruffy tie—as if he’d just been swept over by a gust of wind—Gardini was an accomplished magistrate who worked himself to the bone, his appearance symptomatic of the unrelenting rhythm of his life.

He was accompanied by a noticeably tanned man of rather eccentric appearance. His brown hair had been lightened by the sun along the sides of his head, leading Teresa to deduce that his tan, too, must be natural, the kind people who practiced outdoor sports tended to get. There was a certain elegance about him, a refinement reflected in the clothes he wore, classic cuts in vibrant colors: flamboyant yet entirely tasteful.

Teresa leafed through the most recent notes in her diary but found no description of the man. Her memory was not failing her: they had never met before. But she did have an idea of who he might be.

Gardini walked toward her, holding his arm out for a handshake. They had been friends for many years, but work was work and they had to act in accordance with their respective positions.

“Thank you for coming, Superintendent. I’m sorry to have troubled you at the end of your shift,” he said, addressing her in unusually formal fashion. “This is Gianmaria Gortan, the owner of this gallery. Mr. Gortan, this is Superintendent Battaglia. I intend to put her in charge of the investigation.”

Teresa smiled briefly.

“This is Inspector Marini, my right hand,” she said.

They all shook hands. Teresa noticed that the art dealer’s palm was clammy. A hint of unease that clashed with the polished image he projected.

“It was Mr. Gortan who called us in,” Gardini was saying. “We have a rather unusual case here.”

He hadn’t given her any kind of hint, but Teresa had spent the past few minutes watching the forensics team in the art gallery going in and out of a room she hadn’t yet seen. A camera attached to a photodetector was clicking incessantly, its powerful flash piercing the dim light. If this was a cold case, then something wasn’t quite right. The volume of resources and personnel that had been deployed did not square with what she’d expected to find; no one really cared about deaths that had happened a long time ago. After the blood dries up, Justice is never in any rush to strike her sword: the scales of her balance remain suspended, and her blindfold falls just loose enough for her to look around and find fresher tragedies to set her hounds on.

“Did someone die in there?” asked Marini.

“Not recently.” Gardini sighed. “Come with me; I’ll show you.”

The sealed room was a laboratory equipped with instruments, most of which Teresa had never seen before. A digital microscope gave off a metallic glint under the flashing cameras, and she recognized some colleagues from the public prosecutor’s office—Gardini’s men—who were busy collecting evidence.

“We use this equipment to conduct authenticity tests,” the art dealer explained. “For dating and valuation purposes. We have an expert who analyzes the artwork brought to us on consignment, or by people who simply wish to establish the market value of a piece they’ve inherited—or found in the attic.”

Teresa flipped her notebook open and quickly noted down the date, time and situation, with particular emphasis on the names, physical appearances and roles of those around her. Her recurring nightmare, her most pressing fear, was that she wouldn’t be able to recognize people she knew. She noticed Marini trying to see what she was doing, so she turned the page and doodled something obscene for his benefit. He blushed furiously and retreated.

Teresa gave her surroundings a quick once-over. Everything seemed to be in maniacal order. As she’d expected, there weren’t any mummified remains sticking out of some interstice in the wall or a hiding place under the floor.

“Are we going to need that microscope to find the body?” Marini, back to being her shadow, whispered in her ear.

She batted him away and looked questioningly at Gardini.

“Give us a minute, please,” the deputy prosecutor told the forensics team.

The activity inside the room died down as everyone except the four of them walked out. Teresa saw a pool of light that had previously been hidden from her view.

Gardini motioned at Teresa to come closer, and she took a few steps forward. She was taken aback by something in the deputy public prosecutor’s expression, a kind of trepidation mixed with anticipation—the latter somewhat surprising to see, considering the circumstances. She followed his gaze.

There was a table with an unframed drawing on it, laid out over a glass surface and held flat with small metal weights at each corner. It was the portrait of a woman. It appeared to be roughly fifteen inches in height and perhaps just under that in width. The paper was thick, almost coarse in appearance.

Teresa walked up to it and when she leaned over to examine it, she found she was unable to look away. She stood like that, motionless and wide-eyed with wonder.

True art needs no explanation, she thought to herself, remembering the words of an old high school teacher. And right here was the proof. She put on her reading glasses, attached to a thin chain dangling over her chest, and looked closer.

The portrait seemed to spring up from the paper. There was a fullness, a three-dimensionality to it that was astonishing. It depicted the face of a young woman, a face of such singular grace that it caught you off guard. Her eyes were closed, her long eyelashes lowered onto her cheeks, her lips just slightly parted. She had an air of the exotic about her, but it would have been difficult to describe how. Her moonlike complexion was framed by her dark hair, falling down to her chest and fading out into the edges of the paper.

It was a magnetic, sublime beauty.

Teresa finally tore her eyes away from the face in search of other details.

On the lower right corner of the paper was a date scrawled in shaky handwriting: April 20, 1945. But there was no signature.

More than seventy years stood between that day and this moment now, when Teresa’s eyes basked in the result. Almost a century—yet time was not a measure that applied to this image in any way. In fact, it seemed to have transcended time, eliminated it altogether.

Over her shoulder, Marini was barely breathing. He, too, had been ensnared by the spell the painting had cast over them all.

“Who is it?” she heard him ask. She herself had been on the verge of asking the same thing. Marini had clearly had the same feeling that had already lodged itself in Teresa’s chest: the sensation of having come face to face with a living creature.

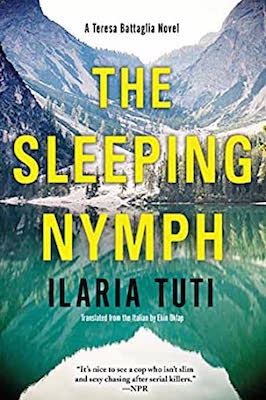

“It’s the Sleeping Nymph,” replied the dealer, surveying the painting. “It was believed to have been lost, but it turned up in an attic among some old paperwork. At least that’s how the artist’s nephew tells it. He brought it to the gallery to have it authenticated, as there’s no signature. But of course it’s purely a formality; there’s no doubt that the artist is his great-uncle Alessio Andrian.”

Teresa had never heard that name before. She couldn’t figure out why Gardini wanted her help with the preliminary investigation. What was she even meant to investigate?

“Are you thinking it might be a forgery?” she asked him.

Gardini let slip a smile. Teresa knew it denoted not amusement but tension, which he released with a twitch of his facial muscles.

“I’m afraid it’s more complicated than that, Superintendent. The analysis of the drawing has thrown up unexpected and somewhat . . . disturbing results. Mr. Gortan will be able to explain it better than I can.”

Teresa straightened her back. The inner scaffolding of her weary body creaked with the effort.

“Disturbing?” she echoed.

“The valuation expert was analyzing the paper and the color in order to date the work,” the dealer began to explain, “and to determine whether or not the date marked on the painting itself conforms with the parameters of the period in which it’s believed to have been created. The painting was executed with charcoal and hematite chalks. The red hue comes from hematite, a ferrous substance that produces this alluring coloring.”

“Yes, I know of it.”

“Until a few decades ago, painters used pure hematite in their work, but nowadays it’s mixed with natural or synthetic waxes. By testing for the presence of these waxes, it’s possible to determine whether a particular piece is recent, or older. The problem is that our expert found something else. He couldn’t identify what it was, so he sent some samples to a lab for further testing.”

“And what did they find?”

It was Gardini who answered, his eyes fixed on hers, the halogen lamp throwing deep, dramatic shadows on his gaunt face.

“They found blood, Superintendent.”

It took Teresa a few moments to understand what he was getting at. She had always thought him to be a practical, sensible man, but it sounded like he’d let himself get carried away a little. She caught Marini’s eye: he looked as baffled as she felt.

Teresa turned her gaze back on the deputy public prosecutor. She tried to think of a tactful phrasing for what she wanted to say, but ultimately knew she’d end up with the most straightforward one, as was in her nature.

“Prosecutor Gardini,” she began, “there are a thousand ways in which blood might have ended up on this drawing. Perhaps the artist cut himself by accident and his blood mixed with the color. Perhaps someone had a nosebleed. Usually, the simplest explanation is also the one that’s closest to the truth.”

Gardini stayed silent, but the way he looked at her was already an answer of sorts. Teresa removed her reading glasses.

“Do you suspect someone was killed in order to make this painting?” she asked him, unable to conceal the note of incredulity in her voice.

Gardini remained impassive.

“It’s not a suspicion. I am sure of it.”

Teresa looked at the portrait again, at that pale face caught in a seemingly endless exhalation. A last breath: perhaps the nymph’s sleep was the eternal slumber of death.

“Why?”

Gardini leaned sideways onto the table and crossed his arms over his chest.

“It’s not just ‘a few’ drops of blood we’re talking about,” he told her.

Teresa felt a numbness spreading across her face, as she did every time she knew she was about to hear a piece of bad news.

“How much?” she asked.

He picked up a file from the table and handed it to her, giving her a minute to leaf through it.

“The Sleeping Nymph is made out of blood, Superintendent,” he told her. “The tests revealed traces of human cardiac tissue on the paper.”

Teresa finally understood, but it was Gardini who voiced what she was thinking.

“Alessio Andrian painted it by dipping his fingers in someone’s heart.”

Cardiac tissue. Human cardiac tissue. Hands entering a ribcage and fingers dipping into a heart. The scene forming in Teresa’s mind was a cameo of folly.

“Mr. Gortan,” she said, turning to the art dealer. “Are you reasonably certain that the author of the painting is Alessio Andrian?”

“I conducted further tests myself to verify the findings and I can confirm, without a shadow of a doubt, that it’s authentic.”

“And how have you arrived at this conclusion?”

Gortan’s lips stretched into the kind of smile reserved to the uninitiated of an art so noble that ignorance of its rules was inadmissible, to be tolerated purely out of politeness. This man, Teresa realized, considered himself nothing less than the high priest of an elite cult, and conducted himself as such. She had been wrong to think of him as a merchant.

“What makes me so sure of the attribution of the work?” Gortan retorted. “Every single detail. The choice of paper, the color, the handwriting for the date, but most of all the quality of the line: the pressure, the angles,” he explained, gesturing gracefully with his hands and spreading wafts of delicate perfume in the process. “It’s the overall quality of the composition, what I would call ‘the artist’s hand.’ That is his true signature. It’s unmistakable. This painting is Alessio Andrian’s Sleeping Nymph.”

He certainly had no doubts. His face was flushed with genuine enthusiasm.

“I must admit I don’t know the artist, nor had I ever heard of the Sleeping Nymph until today,” Teresa conceded.

The art dealer’s clean-shaven face quivered with the passing shadow of a grimace so fleeting that Teresa wondered if she’d imagined it.

“That doesn’t surprise me,” said Gortan. “Andrian isn’t a painter for the masses but for a small and, if you’ll forgive me for saying it, rather select circle of connoisseurs. But all those who’ve had the rare privilege of seeing his work have remarked on its extraordinary artistic essence.”

Teresa was intrigued. Who exactly was this man, Alessio Andrian?

“What do you mean by ‘rare privilege’?” she asked.

There was a gleam in Gortan’s eyes now, something seductive in his manner—the manner of a man who knows he is the custodian of a remarkable story.

“Andrian stopped painting in 1945, Superintendent. He was only twenty-three. His works are numbered one to ten,” he explained. “The portrait of the Sleeping Nymph is believed to be his last, number eleven.”

Teresa noticed that he referred to the woman in the painting as if she had really existed.

“Did he use a model to paint her?” she asked.

Gortan shook his head.

“Nobody knows.”

“Maybe he stopped painting because of what happened when he finished it,” Gardini suggested.

“I suppose you’ll find that out for us, won’t you?” the dealer replied.

Teresa opened her notebook.

“What’s it worth?” she asked.

“Before the blood was detected, I would have said three hundred to three hundred and fifty thousand euros. But now . . . who knows? Maybe even twice as much.”

“Are you saying that this kind of morbid detail can cause an exponential increase in the value of a painting?” Marini inquired.

Gortan gave him a look of disdain, which irritated Teresa.

“No, Inspector. What I am saying is that the value of a painting, and indeed of any work of art, is linked inextricably with its history, the human element that comes with it. Alessio Andrian’s story is undeniably unique, and this latest piece of the puzzle can only add to the fascination.”

Teresa stopped writing.

“What story?” she asked.

“Andrian’s nephew is currently abroad on a business trip but will return tonight,” Gardini interrupted. “We’re meeting him tomorrow for an informal interview. There’s no one better positioned than him to tell us the story.”

“Given the circumstances, I’d rather find out now,” Teresa persisted.

“Andrian was a partigiano, a freedom fighter during the war,” Gortan interceded. “He made his paintings while hiding in the mountains, in between German raids. When the war ended, his comrades couldn’t find him. They thought he was dead.”

“But?” Teresa prompted.

“But he’d actually ended up in Yugoslavia. A family from Bovec sent word out to the Italians across the border that they’d found another Italian in the woods behind their home. The man was in such terrible shape that at first Tito’s militias thought he was dead. It was Andrian. It had been two weeks since he’d disappeared. No one ever found out what he did during that time.”

“They didn’t ask him?”

“Andrian never came to his senses to tell the story.”

“So he died?”

“No, but he went mad. And he never painted again. He never spoke again, either. Ever.”

Gortan fell silent.

“He took the secret to his grave,” Marini mused.

“Not quite,” said the prosecutor, catching Teresa’s eye. “Andrian is still alive, but he’s lived in a vegetative state for almost seventy years now.”

He paused for a moment as if to give them time to prepare for what was to come.

“He isn’t ill, he never has been. But he’s chosen not to walk. He’s chosen not to speak. For seventy years. Whatever happened to him after he painted the Sleeping Nymph, he chose to die a living death. He’s a breathing corpse.”

__________________________________