This month’s true crime roundup features plenty of deep dives into history, from a Guatemalan murder in 1800, to a forensic scientist at the turn of the century, to the many unsolved crimes of the Civil Rights era, and beyond. These books are important reminders of the weight of history, and the intersection of crime and society. Cheerful outlaws, ineffectual civil servants, and driven filmmakers fill the pages below. Each has a story to tell, and it is our duty to listen. Also, they are entertaining AF.

Sylvia Sellers-Garcia, The Woman on the Windowsill: A Tale of Mystery in Several Parts (Yale)

This one starts with a pair of severed breasts, displayed on a windowsill. The image is as shocking to readers today, or to the author when she came across the tale in an archive, as they were to the Guatemalan public under colonial rule, but for very different reasons. Sylvia Sellers-Garcia weaves together the story of the gruesome discovery into the history of colonialism, violence against women, medical science, and the evolving nature of crime and punishment, for one of the most thoughtfully crafted works of true crime I’ve ever seen.—Molly Odintz, CrimeReads senior editor

Kate Winkler Dawson, American Sherlock: Murder, Forensics, and the Birth of American CSI (Putnam)

Dawson, the author of Death in the Air (the story of the Great London Smog of 1952 that killed 12,000 people, as well as a serial killer who strangled eight same women that winter) turns her talents to the story of Edward Oscar Heinrich, who was known as the “American Sherlock.” In his lab in Berkeley, California, he pioneered forensic research that cracked approximately 2,000 cases. This book is a canny biography of the man who brought crimesolving into the modern era, as well as a wise, knowing criticism of the modern era itself, for its not seeking to improve Heinrich’s techniques to ensure greater, safer results.—Olivia Rutigliano, Lit Hub & CrimeReads staff writer

Sam Wasson, The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood (Flatiron)

The story behind the making of Chinatown is just as twisted and fascinating as the film itself. Sam Wasson, who has previously written about Bob Fosse and Gwen Verdon, as well as many other singular figures in entertainment, has crafted an impressionistic work that captures the filmmaking industry at its most creative—and most out of control. Weaving together the stories of Robert Townes, Roman Polanski, Robert Evans, Anjelica Huston, and of course, the character of the film itself, Wasson’s new work of film history is not to be missed.—MO

Sierra Crane Murdoch, Yellow Bird: Oil, Murder, and a Woman’s Search for Justice in Indian Country (Random House)

This remarkable work of journalism chronicles the work of Lissa Yellow Bird, a Native American woman who was released from prison in 2009 to find that her home had been ravaged by an oil boom. When she learns that a young white oil worker has mysteriously disappeared, she begins an investigation into the shady interlopers who have invaded the landscape.—OR

Karen R. Jones, Calamity: The Many Lives of Calamity Jane (Yale)

As we learn from the get-go in Karen R. Jones’ new biography of Martha Canary, better known as Calamity Jane, this outlaw heroine was more of a drunken storyteller in the right time and the right place to create her own legend than someone with a proven track record for outlandish acts. She was, however, a proven and lifelong nonconformist, along with many other independent women in the west. Like any good work of nonfiction about the frontier, Karen R. Jones splits her time between discussing real life and abiding myths, for a fascinating and nuanced look at a complex figure.—MO

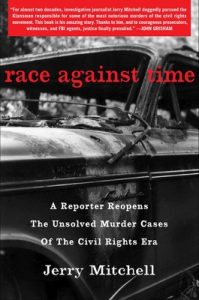

Jerry Mitchell, Race Against Time: A Reporter Reopens the Unsolved Murder Cases of the Civil Rights Era (Simon & Schuster)

Jerry Mitchell’s crucial book investigates the “Mississippi Burning” case, the 1964 murder of three civil rights workers at the hands of twenty klansmen, whose identities and guilt were widely known though they were not prosecuted for the crime. No one was charged with murder. And it took forty-one years for the guilty party to go to trial.—OR