Loretta, who is five, tells me she wants to be a writer when she grows up. If this is my fault—and it must be—I can only say, heaven help my little girl. Still, I am not surprised. We have spent many hours sheltering in place during the pandemic reading and writing books. Lots and lots of books. When it’s her turn to write, we outline and plot. We discuss action and resolution so her stories don’t spin off into madness and chaos. We always make sure there is plenty of room on the page and time in the day for drawing pictures. Loretta is pretty good at a surprise ending.

As always, she is full of questions, so many questions. “Did you always want to be a writer, Mama?” I told her I did but I never told anyone that. Why, she wondered, when she is so open about her future: Author. Doctor. Artist. Schoolteacher. Naturalist. She often asks, “What do you write, Mama?” I tell her part of the truth: I have been writing sports fantasy books for kids with Kobe Bryant, the kind of books she loves with plenty of scary parts—evil gods, nefarious trees, duplicitous family members.

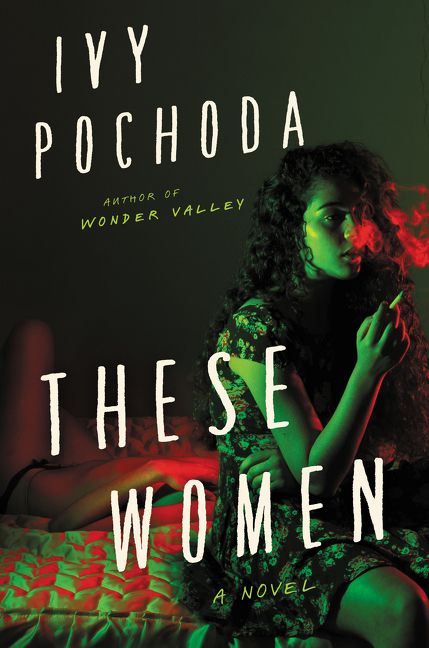

I do not tell her about my grown up books. Why would I tell a five year old that my most recent book is about female sex workers in the shadow of a serial killer? If I told her I wrote dark stories about desperate people in dangerous situations I know Loretta would want me to read them to her. In fact, she’d insist on it. “I’m not scared, Mama.”

I’m a little tired of telling an anecdote at readings and lectures about the accident that made me a crime writer but I’ll regurgitate it here for what I think will be the last time. When I expressed surprised at the noir-ish cover of my novel Visitation Street I learned that my editor was sending it to Dennis Lehane for a blurb. She explained to me that I’d written a mystery. “What did you think you’d done,” she asked. I wondered then and long after at this unexpected literary path.

But in these weeks of reading to Loretta and thinking about what I read to her, I’ve begun to realize that writing crime was something I’d been gunning for from a young age. The books I read and reread as a child and an adolescent, and still turn to as an adult, were often mysteries, gothic and creepy, twisted and twisty.

I’m surprised it took me so long to realize how my childhood literary obsessions fed my adult career. After all, the first story I ever typed on my family’s word-processor owed everything to Sherlock Holmes. My mother loves to remind me that when I read it aloud my father’s shoulders shook with desperately suppressed laughter. I had my Sherlock deliver a magisterial response to a visitor who was surprised that that the detective had already “deduced” his identity: “If you wish to conceal your name, sir, you should cease wearing it on your hatband.” Clearly I was made for this.

I have no idea, of course, whether Loretta will actually become a writer. (She’s currently rehearsing for a role in the circus by teaching our dog Taco to jump through a hoop.) But if that’s a path she chooses, I will suggest she read and reread these five novels for her future life of crime.

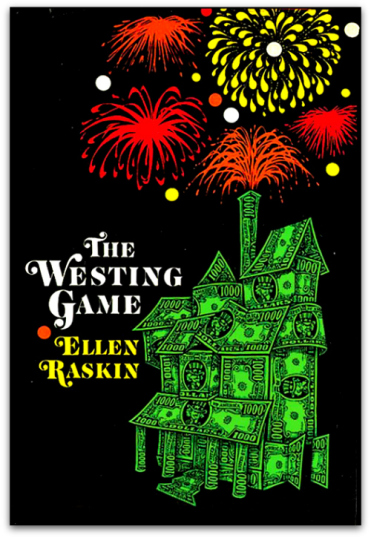

The Westing Game

This was my first favorite book—so much so that I remember some childhood weekends when I’d finish it and immediately start over. Ellen Raskin’s* delightful puzzle mystery is remarkably satisfying and intriguing even to adult readers. Perhaps it first charmed me because of Turtle, the brilliant twelve-year old girl, who solves the puzzle at the novel’s core. But on each rereading I find something new to savor—the profound humanity of the various players of the game, their real world struggles, be they financial, racial, physical, or social. The last page still makes me cry for reasons I’ve never quite understood. Maybe it’s because the book is over, or perhaps because The Westing Game transcends the mystery at its center and emerges as an everlasting story of community and the search for connection.

*I also recommend Raskin’s The Mysterious Disappearance of Leon, I mean Noel.

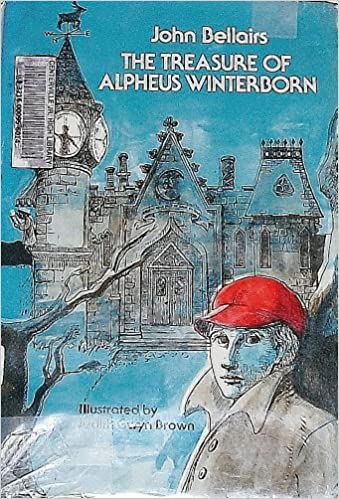

The Treasure of Alpheus Winterborn

I go deep on John Bellairs who is best known for The House With A Clock In Its Walls (the first book in the Louis Barnevelt series). Bellairs specializes in lonely protagonists who are sucked into creepy, charming gothic mysteries in their perfectly drawn working class towns. The Treasure of Alpheus Winterborn introduces Anthony Monday who is beset by anxiety about his family’s finances and their social standing (his father runs a saloon) and his sidekick Mrs. Eells, the town’s cranky and spirited librarian. This unlikely friendship leads to a treasure hunt that ends in a dramatic chase on the library’s spire in the driving rain. Like many of Bellairs’ books, The Treasure of Alpheus Winterborn relies on the perfect pairing of a bookish, yearning kid, an eccentric and charming adult, and an adventure anchored in true gothic spirit.

The Curse of the Blue Figurine

Another entrant from Bellairs, the Johnny Dixon series, kicks off with the delightfully spooky, The Curse of the Blue Figurine. Like the Anthony Monday books, this series features the oddball pairing of young Johnny, who lives with his grandparents, and his crotchety neighbor Professor Childermass, so crotchety that he has constructed a fuss cabinet in his house where he works out his foul moods. Johnny bonds with the professor over their love of Egyptology and ghost stories which inspires Childermass to taunt Johnny with a tall tale about the spirit of local priest who haunts the town church. But perhaps there is more truth than legend to the story. The result is a remarkably chilling adventure that conjures the spirits of the dead, at the same time that it summons a perfect rendition of childhood anxiety, longing, and wonder.

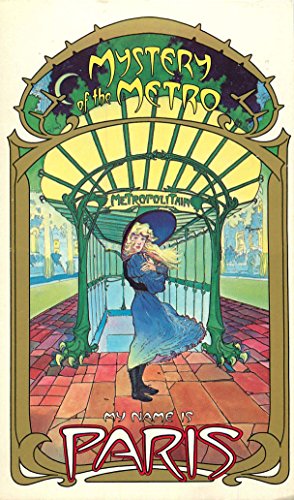

My Name is Paris, Mystery of the Metro

I thought I’d won the literary lottery when I began to read the first book in Elizabeth Howard’s My Name is Paris Series—no, even before I began to read it. One look at the Art Nouveau cover with a glamorous teenage girl in front of the Paris Metro and I was hooked. What could be better than an American heroine plunged into a Parisian intrigue involving a nemesis named Madame Meduse? The My Name is Paris series is stylish and smart, filled with transporting turn of the century details and enough dirty deeds to make any young reader want to travel back in time to solve crimes.

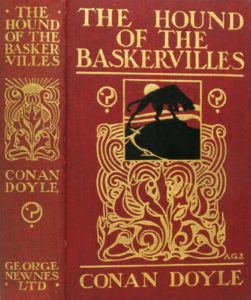

The Hound of the Baskervilles

I was a devoted Sherlockian. (You can see a 1987 New York Times photo of me at age ten in a deerstalker and tweed jacket, a future member of the Baker Street Irregulars at the annual Algonquin Hotel’s Sherlockian Breakfast). This makes it almost impossible to pick a favorite Sherlock Holmes mystery. But, twist my arm, The Hound of the Baskervilles, is mine. I have devoured it across various media—books on tape, television, film, and of course print, countless times. Perhaps it’s the presence of an enormous hound with phosphorescent drool rampaging across the moors that hooks me. (I always imagine a rabid Labrador.) Maybe it’s the wild moors themselves that, along with the deadly canine, capture my imagination. Or maybe it’s the way these elements lift The Hound of the Baskervilles from a simple mystery into something truly horrific, almost delightfully supernatural.