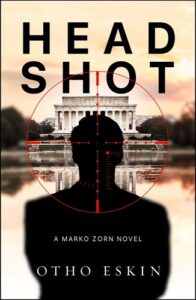

Before I began writing plays and fiction, I served for over twenty years in the United States Foreign Service. During much of that time I was engaged in international negotiations based mostly in Washington and United Nations Headquarters in New York and Geneva, primarily dealing with the law of the sea and with the peaceful uses of outer space. In between negotiations, which took me to many of the capitals of the world, I served in four U.S. embassies abroad as a Foreign Service officer in a wide variety of jobs. I have drawn, loosely, on these experiences in the creation and depiction of places, characters and plot elements, in my novels The Reflecting Pool and Head Shot.

My initial assignment abroad (1963-1965) was to Damascus, Syria. I had just arrived with my family, which included my wife and infant daughter. On one of my first days a member of the embassy staff was showing me around and we stopped our car on a bluff above the city. Parked in the same area were many other cars, all with their radios on full blast, so they could all listen to the Syrian government spokesman. Suddenly the atmosphere changed; all the men jumped into their cars and headed off as fast as they could. “Let’s get out of here,” my companion shouted to me. “There’s an attempted coup d’état and the government has announced an immediate curfew. Anyone found on the streets will be shot.” We drove quickly back to safety through empty streets.

That evening I watched as jet fighters flew low over the city and I saw armed men running through a vineyard near our apartment. A few moments later, a military tank appeared, in hot pursuit. That’s when I had a feeling, I was not in Kansas anymore.

Some months later, while visiting the souk, the ancient market in Damascus, I found myself in the middle of another attempted revolution. The storefront shops all had metal shutters and suddenly I heard them all being slammed shut. The streets emptied and I was virtually alone. Soon the police arrived in trucks, armed with water cannons and men in uniform carrying heavy truncheons. The Syrian government was preparing to suppress an uprising and, although Damascus remained quiet, several cities in Western Syria were bombed into rubble.

Among my jobs in my early foreign assignments was to look after American visitors or residents who got themselves into trouble with the police, usually for possessing drugs. That meant I had to visit some very scary prisons. One was located in an ancient Roman fortress which probably had been used as a prison for over two thousand years. Its condition and ambiance were what you would expect: massive stone walls, dripping with water, and dark, forbidding cells. The Americans held there were terrified. All I could do was to provide them with a local Syrian lawyer who would try to get them across the border into Lebanon—in those days a place of a sanctuary.

From 1966 until 1969, I was assigned to Belgrade, the capital of then-Yugoslavia. While there, I visited what is now the independent nation of Montenegro and I use this experience as background for events in Head Shot. At the time, Yugoslavia was under the iron rule of Marshal Josip Broz Tito and was, at least on the surface, quiet and peaceful. But below that surface were deep historic ethnic and political tensions, some going back a thousand years. On Tito’s death, and after I had left the country, these religious and ethnic tensions erupted, essentially tearing the country apart, leading to internal strife among warring militias and horrific ethnic cleansing, not to mention American bombing targets in Serbia. I watched this from abroad with horror and sorrow. Many of the militia factions were led by local war lords, often generals from the former Yugoslav army. I incorporated some of this in Head Shot as the backstory of the tyrannical rule by a local military figure whose death in Chicago at the hands of an enraged mob leads to a succession of violent acts that initiate the Head Shot narrative.

From 1977 to 1979 I served in Berlin, then the capital of the German Democratic Republic, or East Germany, where I was treated as a spy. I was by then a senior officer in the embassy and my job was to cultivate local sources, both official and non-official, and to report to Washington on political and social developments in East Germany. Here I was living in a true police state. Diplomats’ phones were tapped by the Ministry of State Security, or Staatssicherheit, better known as the Stasi; my home, where I lived with my wife and four young children, was kept under surveillance, our neighbors were interrogated about me and my contacts.

The Stasi was at the time the most feared and repressive secret police agency in the world. They infiltrated every aspect of life in East Germany with offices throughout the country and in every company, factory, school and institution. Reportedly, the Stasi employed one secret agent for every 166 East German citizens. The Main Administration for the Struggle Against Suspicious Persons was the department responsible for the surveillance of members of foreign embassies, which included me, of course.

The Stasi was responsible for the publication of a book entitled Who’s Who in CIA. The book claimed to reveal the names of 3,000 CIA agents serving in U.S. embassies abroad. In fact, it has been reported, less than half that number were, in fact, CIA agents. Many were Foreign Service officers, like me, serving in U.S. embassies.

Who’s Who in CIA was certainly done with the cooperation, if not the direction, of the Russian KGB and with the purpose of compromising the activities of American diplomats serving abroad by making people in other countries suspicious and reluctant to have contact with them.

In a sense, intelligence agencies were playing games with each other. I suspect that the Stasi knew perfectly well who in the U.S. embassy in Berlin worked for the CIA. And the FBI knew who in the East German embassy in Washington were Stasi agents. It wasn’t always a game, though. In one posting, an American I knew was arrested by the country’s security police, tried and convicted of being a spy and executed by public hanging. In the Diplomatic Lobby of the Department of State there is a plaque honoring Foreign Service officers who have been killed in the line of duty. I have known and worked with many of them: killed by terrorists or by the gangster governments they were sent to represent their country. There was at least one tragic consequence to the outing of intelligence agents. In 1975, a CIA station chief was murdered by terrorists. He was one of those listed in Who’s Who in CIA as a political officer.

I was in East Berlin soon after the fall of the Berlin Wall and was having a drink in a hotel bar. At a table next to mine were several men, obviously Western reporters, interviewing a man I recognized as Marcus Wolf, the former head of the East German Directorate for Reconnaissance Intelligence Division. He was the man in the Stasi responsible for the vast East German spy network in the West. Wolf has been described as the preeminent spy master during the cold war and may have been a model for the Karla, George Smiley’s nemeses in John Le Carré’s novels. I tried to eavesdrop on their conversation, but I missed most of what they said. So much for my being a spy. But I was struck by that image: The Cold War was over and one of the master spies from the Soviet Bloc being wined and dined by Western journalists as a celebrity in a fancy hotel.

Life in Washington, where I served off and on for many years in international negotiations, was, by contrast, relatively quiet and peaceful. Except, when it wasn’t. While I was there, The Weather Underground, the radical, militant organization planted a bomb in the Department of State building. The explosion caused extensive damage on three floors, including my office on a floor above. Thankfully, no one was injured in the blast.

In Head Shot I try to capture something of the atmosphere of the diplomatic service. In addition to the scenes involving life abroad while serving in U.S. embassies, there are scenes set in the Department of State itself. One scene takes place in the office of the Secretary of State, a place I had occasion to visit. Other scenes are located in the State Department diplomatic reception rooms.

I have, over the years, had many opportunities to visit U.S. and foreign embassies. The Embassy of Montenegro in Washington DC, is the scene in Head Shot of several major incidents, including a violent shoot out. My apologies to the Ambassador and his staff who, I’m certain, would never countenance such a thing.

I have woven fragments of these and other incidents and people from the world I once inhabited, in the creation of some of the characters and incidents in my work. My novels are part of a tradition of books written by current and former members of the diplomatic and intelligence services. First of all, there is, of course, John le Carré, the wonderful writer and one of my favorites and an inspiration to me, who drew on his experiences in the British Foreign Intelligence Service in his George Smiley novels. Smiley outwits his opponents through intelligence and not through violence. I follow this example in the creation of my main character, Marko Zorn, who hates guns and defeats his enemies through nerve and guile. Other authors who drew on their careers in the State Department and the CIA to create authoritative and compelling plots and characters include Charles McCarry (CIA), author of The Shanghai Factor and The Tears of Autumn, Jason Matthew (CIA), who wrote the Red Sparrow series, and Matthew Palmer (State Department) the author of The American Mission and The Wolf of Sarajevo.

Featured image:

Damascus, Al-Hamidiyah souk, Bernard Gagnon

GNU Free Documentation License, image modified