The first stories I can remember are crime stories. Episodes of Unsolved Mysteries, watched with my mother while my father was away on business trips. My mother, a nightshift ER nurse, had seen the worst of what can happen to a human body up close. This fact radiated outward in palpable waves of anxiety at all times, but especially when my father was away for the night. On those nights, we propped kitchen chairs under the handles of every door in our suburban home and picked up the phone at regular intervals to make sure the line hadn’t been cut, Golden State Killer-style.

The sound of the synthed-out Unsolved Mysteries theme song excited me not so much because it indicated I was about to hear a scary story, but because it signaled my chance to go full Mystery Science 3000 on Robert Stack and his crew of demons and murders (entities who were, oddly, presented as equally viable threats in the Unsolved Mysteries universe). Jokes, I quickly learned, were the best way to cut the tension of our household: if I could make her laugh, my mom might start to relax.

I thought of this weird blend of manic fear and comedic critique a quarter-century later while attending a live show of the podcast My Favorite Murder. At the top of the show, host Karen Kilgariff read a prepared statement warning those who weren’t familiar with the pod (audience members referred to by the hosts as “drag alongs”) that “this is a true crime comedy podcast.” Kilgariff elongated the word “comedy” before adding, “We talk about the worst thing that can happen to anybody here: murder. We also tell jokes. If you don’t like it you can get. the. fuck. out.” She paused between beats of the last four words and, inevitably, the audience (me included) joined in to scream the phrase (which we had memorized) in tandem.

A lot has been written about why women love crime stories. Amanda Vicary, author of the academic study, “Captured by True Crime: Why are Women Drawn to Tales of Rape, Murder, and Serial Killers?” explains her research “shows that women fear crime more than men, since they’re more likely to be a victim of one. My thinking is that this fear is leading women, even subconsciously, to be interested in true crime, because they want to learn how to prevent it.” Vicary also points out, however, that increased knowledge of how crime happens in turn generates an increased fear of becoming a victim. A cyclical pattern in which fear generates a desire for knowledge, which in turn generates more fear. Enter: The Joke.

Emotionally, The Joke punctures the dense bubble of anxiety that shrouds every story of violence. However, the function of the joke isn’t simply to cut the tension. Rather, the tonal shift created by humor also allows for a brief respite, a safe space of contemplation, a zone where our protagonist gets to pause and reflect on her circumstances. My favorite crime stories from the last decade—The Swallows by Lisa Lutz, Oligarchy by Scarlett Thomas, Social Creature by Tara Isabella Burton, Eileen by Ottessa Moshfegh, Bunny by Mona Awad, and everything by Megan Abbott—all feature protagonists who, in the midst of fear or violence, pause to offer a scorching social critique. These women are one part investigator, one part insult comic.

Comedy in the crime novel allows us to watch women navigating danger without feeling the terror that triggers a cycle of anxiety—and it allows our narrator, in real time, to go burn unit on perpetrators. While Abbott and Lutz’s characters often employ the acerbic one-liner of a film noir heroine, Moshfegh and Burton portray women who themselves are the product of patriarchal and capitalist systems. Their respective protagonists, Eileen and Louise, offer an almost unceasing stream of self-deprecating introspection. “And like all intelligent young women, I hid my shameful perversions under a facade of prudishness,” Eileen remarks of herself. “Of course I did. It’s easy to tell the dirtiest minds—look for the cleanest fingernails.” Awad and Thompson, however, offer satirical depictions that point not inward at their protagonist’s own faults, but outward to the way in which large-scale cultural institutions (namely, the academy) fail. Here’s an exchange between a professor and student at the girls boarding school depicted in Oligarchy:

“Because of capitalism, Lissa. Because of your fathers and what they do.”

“Sir, that’s sexist! Some of our mothers might be capitalists too.”

Interestingly, the butt of the joke in these novels is often not the criminal, but the systems that produce them. “Because of the violence of this place,” Awad writes in description Bunny’s backdrop, “existing as it does in the fragile heart of seething poverty, doesn’t exactly feature in the script of the Warren campus tour, which is always lead by some undergraduate tool in designer sportswear who is quite expert at shouting cozy factoids about statue erection and chandeliers while walking backwards.” Awad blends cultural critique about the relationship between poverty, violence, and prestigious universities’ utter denial of their economic complicity in the equation with a spot-on caricature of said universities’ student body. The connection between the system and the product is immediate—and funny.

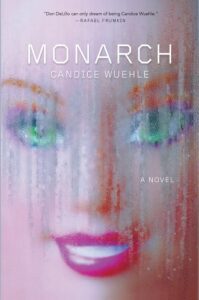

I began my own novel, MONARCH, in the first year of the Trump presidency. I’d published a couple collections of poetry prior and, really, had no idea that I was about to become a “novelist” when I wrote the first sentence of MONARCH: “There is no way to tell the story of a great violence.” I don’t think I believed there was any way to tell any story, actually, when I sat down to write—my mode of expression lived with images and sound, not character and plot. Perversely, it was the decay of any real logic or actual justice in the narratives surrounding me that compelled me to want to tell a story. I wrote MONARCH during the years in which the president’s sexual assault allegations, #MeToo stories, the testimony of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford and Chanel Miller, and victim statements in the trials of Jeffrey Epstein and Larry Nassar hummed ambient under everything. I wrote MONARCH during the years in which chronic abuses of power were excused, reasoned away, or denied. I wrote MONARCH during the years in which it became undeniable that none of the systems I’d been raised to believe were trustworthy, well…were.

This is what I love about the modern crime story heroine: she knows no help is coming.

I think it was for this reason that while writing the especially violent parts of MONARCH, I thought more about the acerbic humor of the women I’d idolized while growing up in the ‘90s (think Darlene Conner and Janeane Garofalo) than actual crime writers who came before me. For plot structure, I did look to Highsmith and le Carré, but for voice and description I was all Daria Morgendorffer. The swerve from heinous to humorous was a way to perform the countercultural work of the stand up comic by highlighting the surreality of discussing—often in graphic detail—acts of violence. The Joke (which is actually always a form of analysis) works to remind the reader to reflect on the conditions the crime they are reading about took place within. The Joke refuses to let the awful occur for the sake of entertainment or, worse, exploitation. In short, The Joke doesn’t let the reader look away.

On a plot level, MONARCH is a novel about the brutal rape and murder of a child that compels my protagonist to hunt down a global pedophile ring. It is also funny. I think my impulse to interject humor during the most difficult parts of writing sprang from that old desire to add levity by cracking jokes to my mom over reenactments of missing persons cases and home invasions. Ultimately, this strategy had the opposite effect: instead of providing an escapist elision of the violence depicted, MONARCH interrogates the cultural conditions under which horrible crimes occur. It also comments on how we tell stories—and who we want our female protagonists to be in a world where traditional systems have miserably failed women.

So this, in the end, turned out to be how I told “the story of a great violence”: I invited anybody who’d shown up expecting all action and no analysis to, well: get. the. fuck. out.

***