JOHN MAY: We’ve not had many serial killers at the Peculiar Crimes Unit, have we?

ARTHUR BRYANT: Not proper saw-off-the-arms-and-legs-boil-the-innards-put-the-head-in-a-Gucci-handbag-and-throw-it-from-a-bridge-jobs, no.

The first stage play I ever saw was Joe Orton’s ‘Loot’, which probably warped my view of the British police forever. The farce involves a much-stolen corpse and naked bank robbers, and features Inspector Truscott of the Yard, an appallingly cheerful copper who specialises in outright lies, burglary and violence. I found him hilarious.

Comedy is tricky ground for crime writers. Slapstick travels but wit does not. If American humor was always benign, a belly-laugh and a pie in the face, on my side of the Atlantic it was harder to pin down; semiotically dense, anarchic and best when bleak, or at least rather cruel. The perfect English insult is one where you walk away thinking you’ve been complimented. The English love to laugh at human weakness, sex, death, embarrassment, sarcasm, class, money and selfishness. No wonder humor can be used to such good effect in crime novels.

The idea that people might exist in a satanic war with their own natures can prove weirdly life-affirming for readers. The leading characters in novels by Muriel Spark, Saki, Beryl Bainbridge and Evelyn Waugh pursue their own aims with a thrilling disregard for conventional morality, sentiment and legality.

I’d been writing crime and comedy for years before I thought of placing a pair of out-of-touch elderly detectives in modern-day London. I decided that Bryant & May (named after a British matchbox) should head a specialist unit not unlike the one in which my scientist father was employed. When his unit decamped stateside, my mother refused to have her new family uprooted. As a result my father was left behind in London and could only imagine what his career might have been. The fictional Peculiar Crimes Unit rewrites his unit’s timeline, bringing his story into the 21st century, my way of righting a wrong for which I had been responsible.

Creating a funny character is one thing, but consciously setting out to write a witty crime novel is another matter altogether. Humour must emerge organically; you can’t simply parachute characters into a funny situation. It also requires a moral viewpoint, if only so that morality can then be flung aside. The tragedy of sudden death and its investigation needs to be treated with gravity, the humour confined to those who have no idea that they’re amusing. People are at their most ridiculous when they’re desperately serious.

How do you get humor to evolve naturally in a story?

It helps to have the right mindset. I’d recommend a sense of amused resignation. And you need the right location. It’s impossible to hang out in London and not have stories to tell. Exaggerated versions of my own experiences usually find their way into stories. So much of my childhood was spent in central London that I grew up thinking Hyde Park was the countryside. We were surrounded by people who seemed normal but became eccentric when they got into scrapes. London’s 2,000 year history is packed with improbable incidents, which are useful for adding colour. A vast amount of historical and geographical research goes into each volume. When I stumble across a press headline that says, ‘Fish and chip shop sells cocaine,’ it emerges in the book as:

‘We’re raiding a funeral parlour? That’s nice, isn’t it? Perhaps we should follow it with a spot of go-karting round the local crematorium.’

I genuinely had no clue as to whether the first book—never intended to be a series—would find an audience. I suspected it was too esoteric to succeed. Bryant & May are now approaching their 20th book together. Virtually every case they’ve investigated has factual roots, and the most unbelievable ones are often the truest. ‘The Bleeding Heart’ has its basis in a grisly local legend that sprang up in Bleeding Heart Yard, just a short walk from my apartment.

It’s an unwritten law that comic crime should avoid topicality, but I’ve thrown in all kinds of time-specific incidents, from London’s terrorist attacks and anti-capitalist riots to the release of undocumented immigrants. A realistic background can help you get away with murder. There are no supernatural elements, no unfair tricks, just diversionary tactics and sleight of hand in bizarre situations. After all, the cases unfold in a city where chapels are sold off as nightclubs, where councils plot to steal parks from children, where residents still tie coloured ribbons on the gates of the Cross Bones, an 18th century prostitutes’ graveyard in a Catholic enclave. Sometimes the only response is dark laughter.

Of course you can get away with anything if you say it with a straight face, which partly explains the power of Agatha Christie—and especially Sherlock Holmes. The Holmes adventures had little veracity. Men went raving mad in locked rooms, or died of fright for no discernible reason. Women were simply unknowable. And even when you found out how it was done or who did it, what kind of lunatic would choose to kill someone by sending a rare Indian snake down a bell-pull? Who in their right mind would come up with the idea of hiring a ginger-haired man to copy out books in order to provide cover for a robbery? What was once deadly serious is now highly amusing.

We still enjoy Hercule Poirot because, like Holmes, he ushers us into a lost world. Christie loved her colonels, housemaids, vicars, flighty debutantes and dowager duchesses. But at the time when they were written surely nobody found them realistic. At least Conan Doyle’s solutions possessed a kind of strange Victorian plausibility, whereas Christie’s murder victims apparently received dozens of visitors in the moments before they died, queuing up outside their bedrooms like cheap flights, and her victims were killed by doctored pots of jam, guns attached to bits of string, poisoned trifles and knives on springs.

You can’t get away with this old nonsense in the present day, of course, but personalities don’t change. Dickens’ characters are still all around us, their traits infinitely reincarnated. I certainly know modern versions of Mrs Jellyby, the philanthropist who fails to see that her own family needs help. As my detectives revel in their own mortality they’re licensed to use plenty of dry graveyard humor. However, I’m careful to respect victims and honor them over villains. There needs to be serious intent underpinning droll events.

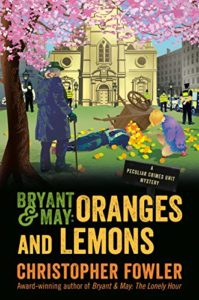

Comic crime gets overlooked by critics who mistakenly assume it must trivialise the unfolding drama. With correct handling the reverse is true; it can highlight everything that’s surreal and absurd about criminals and their investigators. In ‘Oranges & Lemons’ I started by studying London’s nursery rhymes and ended up exploring the history of religious insurrection. If the story is a good one, there’s room for both topics.

Crime novels can use comedy to expose flaws instead of confirming beliefs, leaving readers with plenty of food for thought. A sense of humor is integral to life’s balancing act, but it also needs to be kept in check. I vary the level according to the plot, constructing ridiculous situations around serious crimes. If you don’t like the jokes you can stay for the drama.

As a bookish child I made others laugh to avoid the risk of being bullied. Comedy is a survival mechanism for living. My favorite funny fiction comes from wayward characters in impossible situations. I remember reading a PG Wodehouse story in which two inept twits kidnap a child in order to rescue him and impress a girl, but manage to kidnap the wrong child, and an obscure Spanish story in which thieves choose to steal a painting they’ve picked from an art book, not realizing how enormous ’Guernica’ is. Both involve crimes exacerbated by the misguided intentions of the lawbreakers and accelerated by panic. The Coen brothers have always understood how crucial it is for their audience to know more than the players, so when an incriminating cigarette lighter is left at a crime scene in ‘Blood Simple’ we scream, ‘Pick it up, you idiot!’ They’re not afraid of tackling existential epiphanies either, as private dick M Emmett Walsh is left to die on a bathroom floor, knowing that the last sight in his grubby life will be the underside of a sink.

I never regard my own crime novels as outright comedies because they tend to have tragic elements that arise from the way I work. The first draft is always serious, and the comedy arrives several drafts later. Any minacious situation can develop elements of farce. My most overtly comic crime novel, ‘Plastic’, was based on a true story told to me by a friend who looked after a high rise apartment for the weekend and found herself facing a possible stalker in an eerie blacked-out building. My heroine had an absurdly optimistic mindset that kept the story light. It would have been too easy (and lazy) to write a standard woman-in-peril thriller. An interesting, contradictory character can always provide comic possibilities.

There’s an image that always springs to mind when I’m starting a new Bryant & May novel; London office workers on their summer lunch breaks, eating sandwiches while sitting on top of tombstones. Strange histories are all around them, but they fail to notice that their lunch park is a graveyard. The comedy is already there in the people and places surrounding us—it just needs to be brought out and stirred into a suitably dark brew.