The 1970s saw a spate of vigilantes, troubleshooters, and the like, loosely referred to as denizens of the men’s adventure subset of publishing—descendants of their Depression-era pulp forebears. These paperback original series most often populated spinner racks and shelves in bus stations, newsstands, drug and grocery stores, and some independent bookstores. These characters, mostly men and in some cases women, were tough, resourceful, often Vietnam vets or ex-spies. Loss and revenge were recurring themes among them—the Batman syndrome, if you will—where in the aftermath of a devastating incident, often a murder of a loved one or close friend, they took up their one-person war on crime and evildoers.

Joining in the mayhem was the likes of Remo Williams, the Destroyer; Baroness Penelope St. John-Orsini a.k.a. the Baroness; Angela Harpe, a rich, kick-ass sister called the Dark Angel (“she owned the most lethal weapons a black chick ever packed, including her luscious, highly-trained body”); a rugged Native American private investigator who went by his last name, Dakota; and Robert Sand, international man of action, sword and martial arts master, the Black Samurai—realized on screen by karate champ turned actor Jim Kelly.

Then there was Joe Radcliff by Roosevelt Mallory.

“The driver felt the impact and heard the deadening thud. He saw the woman’s body fly into the air, land on the hood, then roll up over the windshield and across the roof of the car. . . . He decided to head for home, in the Santa Cruz mountains. Good fresh air, beaches, Monterrey, San Francisco. It would be good to get home.”

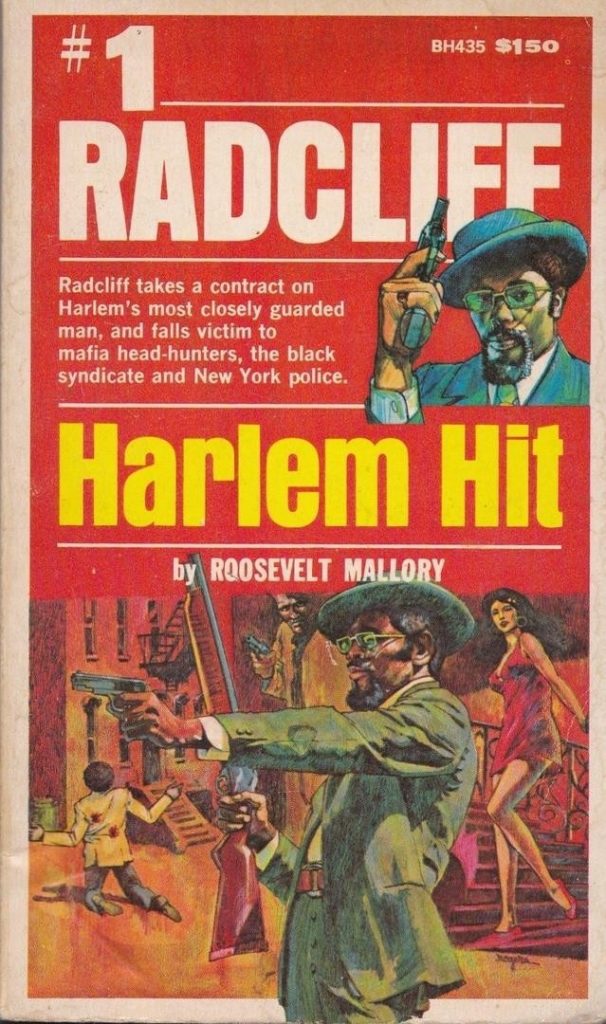

This is from an early passage of the first book in the Radcliff the “Hit-Master” series, Harlem Hit (1973). Mallory wasted little time establishing the character, a cold, amoral, ruthless killer for hire, with a specialty of not overtly warring against the mob but working for them and other shady types. Before he does this, the reader is informed the woman he whacked with his car was plotting the murder of her current husband, who helped her take out the previous one. The dangerous husband acts first, paying Radcliff’s tab to whack her.

* * *

Though Radcliff was also a Vietnam vet (in keeping with the trope of the times) and could dispatch his fellow human beings with little or no inner reflection, there the similarity ended with those hundreds of other paperback original series characters. Radcliff came on the scene before Lawrence Block’s affable, stamp-collecting hit man John Keller and Barry Eisler’s taciturn contract killer, Vietnam vet John Rain, who, like Charles Bronson’s The Mechanic (1972), makes his hits look like accidents. Radcliff, and we learn this is a code name, even showed up before his fellow Holloway House scribe’s Larry Jackson was unveiled in Daddy Cool (1974) by Donald Goines. Jackson, a.k.a. “Daddy Cool,” is a middle-aged hit man who specialized in dispatching his victims with his handmade knives. He found himself in a Shakespearean dilemma as he tried to save his wayward teenage daughter from falling for a jive pimp and slipping into “the Life,” as Iceberg Slim might have put it.

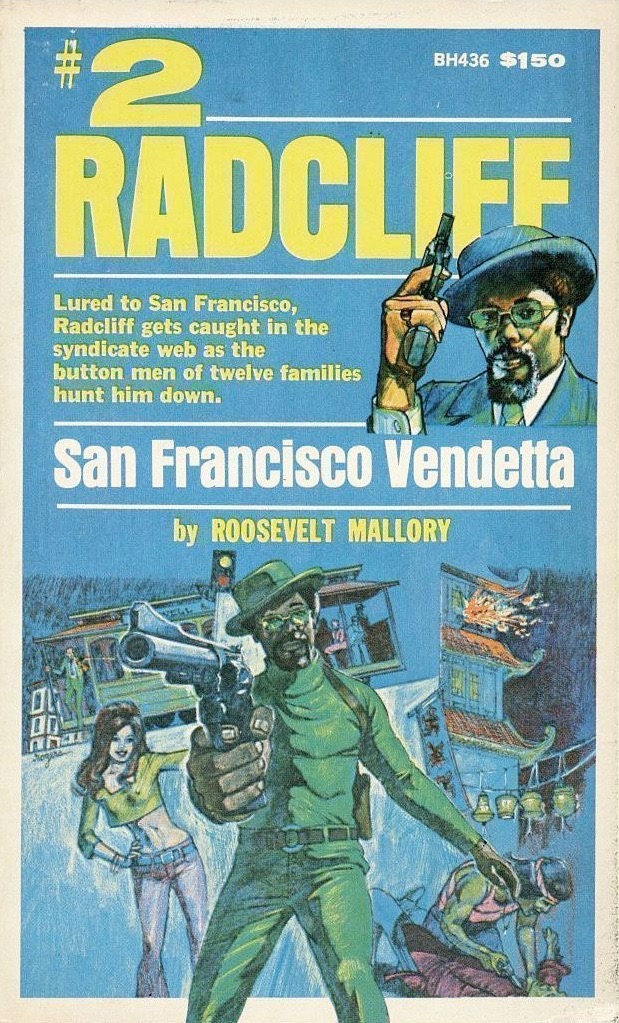

Radcliff had no family and no qualms about his chosen line of work. He is not motivated to get even after the murder of a wife or child, for his motivation, as espoused by 50 Cent, was “Get Rich or Die Tryin.’” In his second outing, San Francisco Vendetta (1974), Radcliff observed, “he calculated that he was knocking off VC for only fifty bucks a head. He figured that the underworld would pay him more for knocking off their own kind than the good guys would pay him for doing so.” As Justin Gifford observed in his book Pimping Fictions: African American Crime Literature and the Untold Story of Black Pulp Publishing (2014), Radcliff personified an aspect of the fruits obtained in fantastical utopian black crime novels.

Gifford specifically singled out another Holloway House unsung star, Joe Nazel, whose Iceman series portrayed Henry Highland West, a players’ version of Doc Savage crossed with Robert “Iceberg Slim” Beck. West was a cat who made ducats in the flesh trade and built his mega-casino-brothel in the Nevada desert, fifty miles in from Las Vegas. Qadaffi-like, he had a guard of kung fu’ing women (his top security being Kim, an Asian chick with serious martial arts skills, and the black Solema, a weapons specialist), patrolling armed helicopters, and a computer in his “Brain Center” worthy of the Machine in the television show Person of Interest.

Iceman and Radcliff become hyper-aspirational pulpish expressions of the masculine end of the Black Power and civil rights movements, with healthy doses of comic book sensibilities. Unlike their antecedents, the adventurer-millionaires of the 1930s—the aforementioned Clark Savage Jr., Richard Wentworth (the kill-crazy Spider), and Richard Henry Benson (the Avenger), to name three—we saw how they got their hands dirty, making their stacks. Surely Wentworth and company, well-off in the depths of the Depression, must have squelched a strike or two by some dirty reds at one of the factories where they were stockholders. Or imagine Doc getting on his experimental visi-phone phone to some hapless flunky in Hidalgo, mentioning calmly that the last shipment of gold from his private mine, in their country mind you, was light and this best not be repeated next time lest the Bronze Devil have to come down there and show them how to count.

The headhunting Hit-Master had a swank, fortified pad in the Santa Cruz Mountains, traveled by Lear jet to his jobs and was aware that as in the first novel, taking a contract by the mob to wipe out a would-be black nationalist leader, he can’t trust anybody, including his employer. In Harlem Hit, Radcliff is being set up for a double cross by the Syndicate, who intend to bump him off after he takes care of one Leroy Johnson. The killer is brought in to take out this firebrand who is putting black folks in charge of the action uptown. Like a grander thinking Deke O’Malley, the slick hustler in Chester Himes’s Cotton Comes to Harlem (1964), Johnson is not out to take over the local rackets for the betterment of his people but to solidify his position as the uptown Godfather.

The plan is to use two other imported black killers to make it seem like it was a black-on-black affair and distract the Feds from the mob having a hand in the deadly machinations. The first book sets in motion events that will play out over the course of the subsequent three other Hit-Master novels. While obsessive, Radcliff wasn’t out to take down the Mafia like the Executioner, the Butcher, and so on, but that’s what he winds up doing. While Mallory doesn’t flinch in portraying the ice-in-his-veins nature of his main character, we the reader root for him as he takes on qualities of the anti- hero in his bloody run-ins with La Cosa Nostra.

Curiously, but in keeping with his white paperback-tough-guy contemporaries, Radcliff isn’t about upsetting the status quo. In San Francisco Vendetta, Radcliff is lured to San Francisco to take a hit job, but this is actually a trap set by the syndicate to pay him back for what he did to their members in the previous novel. In the Bay Area, surviving a shoot-out in Chinatown and realizing he’s been set up, Radcliff pays a visit on a white ex-G.I. buddy to obtain the more serious fire- power he’ll need.

The friend, Barry, is some kind of activist who espouses violence as a way to make change. His stance infuriates the stone-cold killer who reflects, “Radcliff did not like Barry’s philosophy nor his organization—an organization of terrorists with the primary mission of making the world just by killing the affluent.”

Interesting that Radcliff should see himself as part of or at least have an affinity for the elite . . . or maybe he was just being pragmatic. Unlike the protagonist of Sam Greenlee’s 1969 novel The Spook Who Sat by the Door or Goines’s radicalized gangster Kenyatta, Radcliff knew where his bread was buttered. Did Radcliff hope that as the syndicate sought to legitimize itself by buying into mainstream capitalist pursuits with its ill-gotten gains there’d still be a place for him at their table?

That hope must have been dashed in book three, Double Trouble (1975). In this outing, the mob brings in a ringer, a double for Radcliff, who kills a cop in Los Angeles. This compels Radcliff to come to town to straighten this shit out and to change his appearance. He shaves off his short beard and medium-long afro, eschewing his usual gold-rimmed, rose-colored shades.

In book four, the final in the series and, as far as can be determined, the last book ever published by Roosevelt Mallory, New Jersey Showdown (1976), Radcliff may not be ready to join his friend Barry’s band, but he is looking to retire. The book opens with Radcliff in his fortified pad with the blonde Angie Redman, who was his steady companion in the series. Like Clare Carroll in Donald Westlake’s Parker novels, where Parker maintains a humbler abode than does Radcliff on a lake among similar vacation-type homes in the woods, she’s a civilian but a constant in his life.

The two enjoy the Hit-Master’s getting out, but of course a man like Radcliff, can never get out. The grown sons of the Mafia chieftain he iced in book two strike back.

Angie is hospitalized after acid is thrown on her face, and a contrite Radcliff visits her there. Later, she’s thrown out the window of her room and killed. Her murder shakes Radcliff, the brutal act breaking though his hard shell and for once it is personal. At her burial he swears: “Now he could turn his attention to who was responsible for this. A promise of vengeance was not necessary in Radcliff ’s world. It was automatic.”

The book ends enigmatically after the antihero wipes out the scum responsible for killing his main woman. Was Radcliff out of the business or not?

* * *

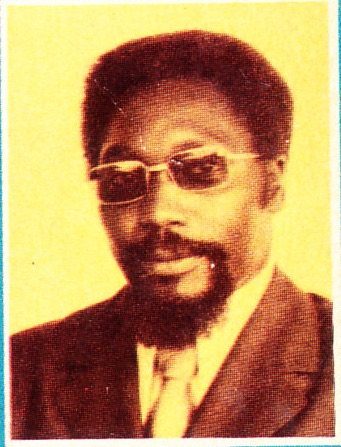

Hoping to know why he didn’t write more Radcliffs or other books, I decided that the hunt for Mr. Mallory was on. There were a few dead ends, including former Holloway House editor Emory Holmes not knowing what had happened to him. But thanks to the gumshoe work of Kevin Burton Smith of the Thrilling Detective website, a lead developed. In the March 1974 issue of Measure, an internal publication of Hewlett-Packard whose subtitle read: “For the man and woman of Hewlett-Packard,” damned if there wasn’t a profile of the author. In an unaccredited piece titled “Get Mallory!” it’s revealed that Mallory, a TV director in their Data Systems department, had been a high school dropout, though a top student and football player. He joined the army, then the coast guard, where he became an electronics technician and then an instructor in electronics. When he was discharged, he entered the growing field of computers and in 1966 joined Hewlett-Packard as their first computer instructor.

Mallory said he started writing the first Radcliff novel after seeing a blaxploitation flick about a hit man. “There were all these tough things going on—but no continuity. Bad Writing!” he’s quoted saying in the article. Though he doesn’t name the film, it might have been the 1974 movie Hit Man with Bernie Casey that he was referring to. He goes on to state that he went to work and wrote the first draft of Harlem Hit. Eventually it landed on an editor’s desk at Holloway House. In this version Radcliff doesn’t survive. But as with what occurred to Parker in his first novel, The Hunter (1962), when Westlake killed him off as well, both men took their respective editor’s advice and had their protagonists live.

In the piece it’s stated that fifty thousand copies of Harlem Hit had been sold and that Mallory had enjoyed some sweet royalties and advances for that book and the upcoming San Francisco Vendetta. The money has “enabled Mallory to expand his life style somewhat along the lines of the hit master—at least in such material manifestations as custom clothes and favored wines.”

It also appears that Radcliff paved the way for two other contract killer efforts from Holloway, The Big Hit (1975) by James-Howard Readus and Black Hit Woman (1980) by Laurie Miles, as told to Leo Guild.

Yet given the shaky accounting Holloway House was known for, the assertion concerning money definitely suggests a deeper examination. For instance, Dan Roberts, in his article “Holloway House: The World’s Largest Publisher of Black Experience Paperbacks,” stated that the combined sales of Iceberg Slim’s books were more than six million copies (Paperback Parade, no. 78, July 2011). But as recounted in the 2012 documentary Iceberg Slim: Portrait of a Pimp by Jorge Hinojosa, Robert Beck mostly didn’t see that kind of money, even given that one of Beck’s books was made into the 1972 movie Trick Baby and he got $25,000 in option fees. Beck, like a character wrought from a William Burroughs novel, found himself in his later years, this once smooth pimp and hustler, going bald, taking on the role of an exterminator, a rat and roach killer who had to make ends meet. Despite his infamy and apparent plentiful sales with Holloway House, Beck died at seventy-four from various ailments in hospital in Culver City, a small municipality next door to LA, a day after the 1992 Rodney King riots erupted.

Getting in touch with the Hewlett-Packard Alumni Association, the word back was that though Mallory wasn’t a member of the group, the individual who corresponded remembered “Rosey,” as he referred to him in an email. He said he’d heard the writer was deceased and, according to some information he passed along, was pretty certain Roosevelt Mallory had died in 2007 in Elk Grove, California.

“Yes, I met him when I started the four books that I did,” Monte Rogers said in an e-mail. Rogers was the artist who rendered the dynamic montage-type first edition covers of the four Radcliff books. “Nice guy, very soft-spoken,” Rogers also noted. He said the Holloway House editor and Mallory provided photos to him for references, and it’s evident as the Rogers covers have tucked under the Radcliff logo a depiction of the Hit-Master in a homburg and tinted glasses, his preferred .38 at the ready, an illustration that looks a lot like Mr. Mallory.

Go on with your bad self, sir.

*

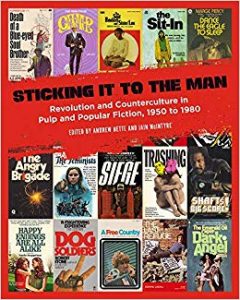

Excerpted from Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980. All rights reserved. Courtesy of PM Press.