In the first few moments of the black-and-white pilot episode of Get Smart, the camera hangs over an audience in a concert hall—Symphony Hall, the narrator tells us, in Washington D.C. Somewhere in the city is the headquarters for a secret counter-espionage organization known as “CONTROL.” And as the camera moves around the audience, capturing the group in evening dress watching in rapt silence as the orchestra plays, the narrator informs us, that somewhere in the audience “is one of CONTROL’s top employees, a man who lives a life of danger and intrigue, a man who has been carefully trained never to disclose the fact that he is a secret agent.”

At that very moment, in the middle of the concert hall, a phone rings. It’s a loud, jangly telephone ring, the kind from a mid-century rotary phone, and it echoes throughout the venue. Watching this scene in the twenty-first century, it might not seem so jarring; how often have we sat inside crowded theaters and had our viewing experiences disturbed by the loud ringing of a phone? But this episode is from 1965, and so when the phone goes off in the middle of the theater, the patrons look around incredulously. A man stands up and hastily exists the theater and when he does, the ringing travels with him, out into the hall. Ducking into a supply closet, he takes off his right shoe and removes the bottom, revealing a tiny, compact phone receiver with built-in rotary dial along the sole. “This is Smart,” he says into the shoe (which it is, but then he elaborates): “Maxwell Smart… Agent 86.” He learns from his boss that the evil organization KAOS is up to a nefarious plan, and so promises to get right down to headquarters. Of course, this will take a moment, because in the course of answering his shoe-phone, he has unwittingly locked himself in the closet.

Get Smart, about the exploits of the blundering but sincere secret agent Maxwell Smart, ran for five seasons across NBC and CBS from 1965 to 1970—totaling 138 half-hour episodes, all in color except for the first. The series was created by Mel Brooks (a man who needs no introduction) and Buck Henry (a man who needs no introduction but should get one just in case; you know him as Liz Lemon’s father and he also won the 1967 Best Original Screenplay Oscar for writing The Graduate). The two developed it at the suggestion of studio executive Daniel Melnick, who recommended cashing in on the mid-century Bond-imitation craze that led to the creation of TV shows like I Spy, The Avengers, and Mission Impossible. Despite its familiar company, Get Smart remained singular for its creativity from the get-go. Henry wanted a Bond framing appointed with an Inspector Clouseau-style hero, leading to unique brand of ridiculousness that had not been seen on TV before: undercover hi-jinks and, well, overcover ineptitude. “It’s an insane combination of James Bond and Mel Brooks comedy,” said Mel Brooks, himself, in an interview in 2008. “It has a wonderful fusion and special effects and comedy, which is very rare. Usually, when you get big special effects pictures, sci-fi and things, there’s little or no comedy. Or it’s a domestic comedy and there’s not one special effect.” If you have not seen it, think ‘Amelia Bedelia in a skinny tie.’

Get Smart, about the exploits of the blundering but sincere secret agent Maxwell Smart, ran for five seasons across NBC and CBS from 1965 to 1970—totaling 138 half-hour episodes, all in color except for the first. The series was created by Mel Brooks (a man who needs no introduction) and Buck Henry (a man who needs no introduction but should get one just in case; you know him as Liz Lemon’s father and he also won the 1967 Best Original Screenplay Oscar for writing The Graduate). The two developed it at the suggestion of studio executive Daniel Melnick, who recommended cashing in on the mid-century Bond-imitation craze that led to the creation of TV shows like I Spy, The Avengers, and Mission Impossible. Despite its familiar company, Get Smart remained singular for its creativity from the get-go. Henry wanted a Bond framing appointed with an Inspector Clouseau-style hero, leading to unique brand of ridiculousness that had not been seen on TV before: undercover hi-jinks and, well, overcover ineptitude. “It’s an insane combination of James Bond and Mel Brooks comedy,” said Mel Brooks, himself, in an interview in 2008. “It has a wonderful fusion and special effects and comedy, which is very rare. Usually, when you get big special effects pictures, sci-fi and things, there’s little or no comedy. Or it’s a domestic comedy and there’s not one special effect.” If you have not seen it, think ‘Amelia Bedelia in a skinny tie.’

One of the reasons for the series’ success was its veritable jamboree of an investment in the confidential protocols of agent-hood. Get Smart is about the flashy stuff, the cool stuff. Max has a beautiful red convertible, yes, but even more fun than the car is that the secret entrance to CONTROL headquarters is in a phonebooth. Get Smart understood that the appeal of being a secret agent is cloak-and-dagger hoopla, a year before Mission Impossible‘s communiques started self-destructing all over the place.

The Bond franchise may have set the precedent of turning ordinary objects into high-tech spy gadgets, but Get Smart always seemed especially interested in the—shall we say—ontology of this trope. What inventions would a spy need? What inventions should be created for him? How do you give a spy everything he needs on his mission while also giving him everything he needs to blend in? And then take it to an extreme?

Nothing highlights its unique nature than Get Smart‘s strangest gadget, “the cone of silence,” a rigging of giant plastic bubbles that spies can stand in to ensure their conversations are not overheard. Only, it’s really hard to hear in them. “[Buck Henry] was gifted with a great imagination,” Brooks told The Hollywood Reporter after Henry’s death in January 2020 at the age of 89. “He came up with that amazingly funny concept of the ‘cone of silence’ in which no one could hear each other.” Series regular Barbara Feldon ruminated, decades later: “When they dropped the cone of silence, the cast always loved watching because it was silliness taken to the most delicious extreme.”

what happens if you give a spy unimaginable resources that allow him to navigate the world with the utmost clandestinity, and he still sticks out like a sore thumb?Sometimes the show’s thoughtfulness led to inventions so surprisingly sensible, they feel modern now—like Smart’s mobile phone. It’s not just that Get Smart‘s secret phones were in shoes—sometimes they were in bars of soap, clocks, and once, a cheese sandwich. “I guess Buck Henry and I actually invented the cell phone,” Brooks said. “We didn’t know we were doing that.” Most of the time, Get Smart underscored the excessiveness and even the ridiculousness of fetishizing such gizmos and protocols, but it did so by finding the fun in them. It seems to have settled on a central thesis that asked, instead: what happens if you give a spy unimaginable resources that allow him to navigate the world with the utmost clandestinity, and he still sticks out like a sore thumb?

Brooks and Henry had intended to satirize the American intelligence complex, lampooning a governmental outfit they felt had too much pomp and not enough circumstance. They wanted to represent, in Brooks’s words, “the earnest stupidity of organizations like the CIA.” In other words, the gambit suggests that when you take away all the contraptions and technologies of powerful espionage groups, what’s left is just bunch of nincompoops.

But Get Smart feels too buoyant and heartfelt to be a full-on political parody, even though ABC found it offensive and passed on it. It is not a Cold War burlesque; there are no bureaucratic bozos or atomic ultimatums, no anxious dances between posturing nuclear powers. The series lacks the edge of Dr. Strangelove and eschews the allegory of The Mouse that Roared. How does Get Smart feel so minimal in its sardonicism? It might might be that in true satire, the entire premise is itself an exaggerated joke but is is delivered seriously. Get Smart is the reverse: its premise is serious (or at least, asks to be taken at face value) but it is delivered via jokes.

In other words, Get Smart’s secret government spy organization, CONTROL, does actually have to deal with tangible threats—from the diabolical global syndicate KAOS (pronounced like “chaos”), and its many evil members, including the most-recurring villain, Siegfried (Bernie Kopell). As does the titular organization of its 60s TV contemporary, The Man from U.N.C.L.E., CONTROL takes these threats seriously, and addresses them swiftly. It just happens to be funny, the way it all goes down.

But the biggest reason Get Smart is so sweet, despite its mocking intentions, is its agents, themselves—most of all, its hero. Agent 86, Maxwell Smart (the rubber-faced, announcer-voiced comedian Don Adams), isn’t an everyman or a fish-out-of-water, but he might as well be. Initially unassuming and unobtrusive, Smart has been over-prepared for spy games, but sorely lacks street smarts or general wherewithal. He’s bumbling, clumsy, easily confused, a little naive, too convinced of his own skill, and very oblivious. He’s incapable of navigating, and often suspicious of, the most ordinary things, yet he can diffuse whatever high-tech weaponry he encounters and outwit innumerable bad guys. But along the way he’ll crash into things, misidentify important contacts, lose invaluable items, and ultimately make himself as conspicuous as possible. In the words of writer Bill Higgins, he unites “earnest seriousness with complete cluelessness.” In the words of Buck Henry, he is “very boastful and very stupid.”

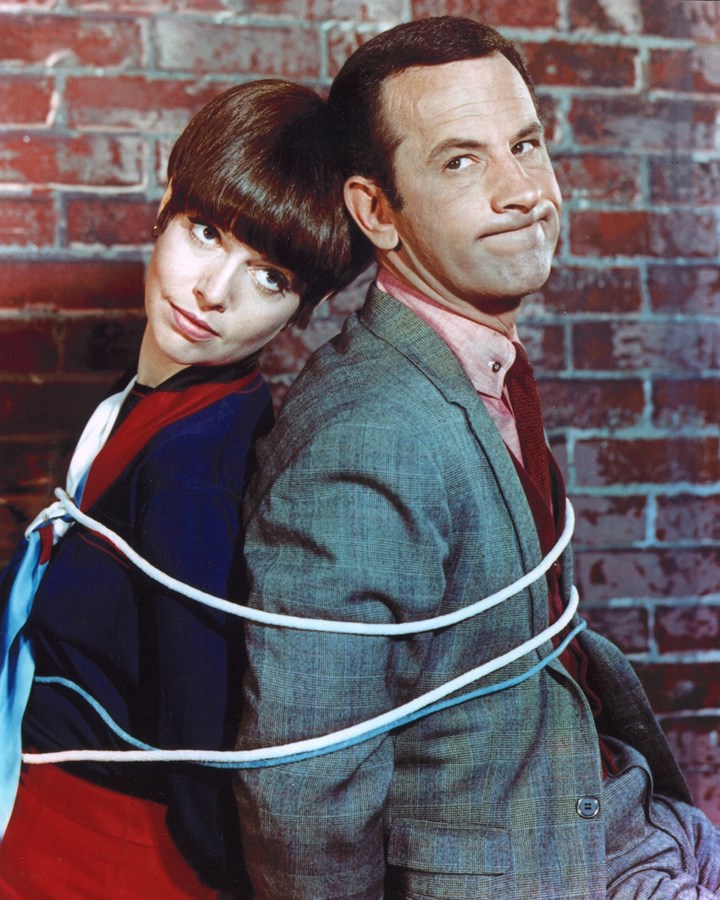

Max is accompanied on his adventures by several equally memorable characters, namely the perky, highly-capable love-interest Agent 99 (the delightful Barbara Feldon), and eventually, a humanoid robot named Hymie (the adorable Dick Gautier). Agent 99 is Max’s constant companion, a kind, competent foil to his unaware buffoonery. Hymie (a beloved staple despite only having appeared in six episodes) is, rather like Max, more extreme in his unsuspecting nature—but this is because he is a robot and takes things rather literally. Also on their side is the Chief of CONTROL, played in polite deadpan by character actor Edward Platt. But in this no-nonsense company of straight-men, Max stands out even more for his goofiness. A personal favorite among the series’ countless funny moments features Max trying to make a cool, collected entrance through a beaded curtain hanging in a doorway. But he causes all the beads to fall off their strings when he attempts to part the curtain.

Brooks and Henry were adamant that the ultimate success of the character Max Smart tracked to Don Adams, himself, since the character could easily wind up pompous and self-important in less-attentive hands. (In Brooks’ words, “You want to be as smart as you can about being stupid.”) The character had originally been written with the deadpan comedian Tom Poston in mind, but Adams had been cast since he was already under contract with NBC. But he proved perfect for the part. His clipped enunciation is so sharp, it is almost pointy. Smart is deliberate, ever-serious, hyper-focused. But the confused and inept sentiments that fly out of his mouth run in intense contrast to the deliberate manner of his speech. But Smart is never-long-winded; he’s quick to speak, just not quick-witted. The effect is hilarious.

Brooks and Henry were adamant that the ultimate success of the character Max Smart tracked to Don Adams, himself, since the character could easily wind up pompous and self-important in less-attentive hands. (In Brooks’ words, “You want to be as smart as you can about being stupid.”) The character had originally been written with the deadpan comedian Tom Poston in mind, but Adams had been cast since he was already under contract with NBC. But he proved perfect for the part. His clipped enunciation is so sharp, it is almost pointy. Smart is deliberate, ever-serious, hyper-focused. But the confused and inept sentiments that fly out of his mouth run in intense contrast to the deliberate manner of his speech. But Smart is never-long-winded; he’s quick to speak, just not quick-witted. The effect is hilarious.

In an interview, Henry noted that Adams’ hyper-enunciated voice had been inspired by the actor William Powell’s presentational delivery in his detective roles. But his jokes were all his own. He gave Smart many running jokes, some from his former comedy acts. “Missed it by that much” he would say, whenever he missed something by a mile. In his best-known gag, often repeated, Smart would make a threat or embellish a point to an unbelievable degree, watch as those around him revealed they did not believe him, and then whittle down his parameters, asking them “would’ya believe…” a few times as he brings his claim down to the ground.

But Adams’s facial expressions are what really sells the character. Whenever he knocks something over or gets himself in an awkward situation, he rends his face into a frozen-eye-roll of frustration, or sucks his in his lips to make a heavy, wide, straight line. But he’s not quite disgusted at himself, he’s annoyed at the situation. There isn’t a scrap of self-pity in there. As is often the case with such silly characters in ensembles, the key to his being the goofball to everyone else’s straight man is that Max seems to believe he’s just as capable as everyone else. The world isn’t out to get him, but it’s really inconvenient at times. It’s a flawless effect.

Get Smart was so beloved that it was revived several times after the series ended in 1970: an unofficial TV movie in 1980, an official sequel film in 1989, a official one-season revival series in 1995 (in which Max is now the head of CONTROL), and a remake in 2008 starring Steve Carell. None had the success of the early series, however. Throughout its original tenure, Get Smart was nominated for fourteen Emmy awards and won seven, including three for Adams. Brooks said, of his committed, consistent performance, “He wasn’t just doing a job, he knew it was his life’s work.”