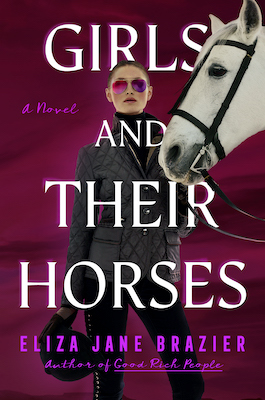

Maple’s mother had insisted she wear riding clothes to the horse stable, even though they weren’t there to ride. They were there to feed the horses carrots. They had brought a big bag of them. The stable was only a mile away from their new house. It had been part of the promise of moving to California.

“Rancho Santa Fe has horses,” Maple’s mother had told her, like there weren’t horses everywhere in Texas. “The first thing we’re going to do is find you a new place to ride.”

Heather sometimes seemed to genuinely believe that Maple loved horses just as much as she did. It wasn’t that Maple didn’t like horses; she just thought they were a little scary, especially the horses at this barn. They were huge and immaculate, nothing like the unkempt quarter horses in Amarillo.

Maple was turned out in breeches, a Cavalleria Toscana shirt and gleaming tall boots. Her mother had taken her to Mary’s Tack and Feed yesterday and selected thousands of dollars’ worth of riding clothes.

“Anything you want,” she had kept saying.

Maple had had no idea what she was supposed to want. Her mom ended up picking, which satisfied them both.

But now Maple felt silly, dolled up in a stranger’s barn—her hair was even in two French braids—like she was auditioning for the role of rider. What if someone saw them? Not only was she overdressed, but they were breaking the rules. There were signs everywhere that said not to touch the horses.

“Those are just for people who don’t know horses,” Heather said. Heather herself wasn’t exactly a pro. She had taken lessons in her youth. She had told Maple the story hundreds of times. How she had been the best rider, until her dad left and she was forced to quit.

She’d had to sell her horse. She’d had to stop going to the barn.

Maple had been told that story so many times it had imprinted itself on her psyche, become an integral part of how she saw her mom—hair in two braids, shiny black boots, sitting outside the arena while the other girls rode their fantasy horses, out of reach.

It wasn’t fair. The world owed Heather horses.

Maple’s mother could have ridden herself now. She had even taken a few lessons, but she always ended up frustrated. It wasn’t the same. It wasn’t what she wanted. It didn’t fix that event, as if the only way into her past was through her daughters’ future.

Heather preferred to watch her daughters ride horses. First, Piper, who had been a natural but who had quit when Heather pushed too hard. And now Maple, who was talentless and slightly fearful but willing.

Maple had always been a little captivated by her mother, who was beautiful, who was made even more beautiful by her strange, specific dreams. Heather wanted Maple to ride horses. She wanted her daughter to dress a certain way. She wanted Maple to have the right friends. She didn’t care about the things other moms seemed to care about—grades and morality and even happiness.

“No one’s happy,” she had once assured Maple, offering a crooked smile‑frown. “Don’t worry about it.” She had pressed her daughter’s hair down. “I wish someone had told me that when I was your age. Then maybe I wouldn’t have thought I was missing out.”

Maple knew her mom had intended to make her feel better, to make her think about her own life, but instead it had made her think about her mom. When Heather kissed Maple’s dad, when she grinned on vacation, when she had congratulated Maple at her elementary school graduation, Maple thought: She’s not really happy. She just seems happy.

Right then Heather seemed happy, climbing up the rungs of a pipe corral to get a better look at a horse whose name was Desi, according to the engraved plaque outside his stall.

“You should ride this one,” Heather said. “It would look so good with your hair.”

Desi was huge, probably over seventeen hands—in horse measurements, a hand was four inches, or the width of a hand. He looked a little spicy, prancing around the far end of the stall, showing the whites of his eyes. He was wrong for Maple in every conceivable way except one—his golden palomino coloring—and that was all her mother saw.

Heather stretched her palm out, which seemed to make Desi more nervous. The gelding tossed his head, swishing his golden mane. “He’s perfect for you.” Heather hopped down, startling the horse.

Heather adjusted her outfit and scanned the deserted aisle. She had dressed herself in discreet wealth. Everything expensive was slightly hidden: slivers of diamond earrings tucked beneath her hair, no logos on her leather purse. Her shirt was floral, simple. She could have gotten it from Walmart, but she hadn’t. She had gotten it at a boutique in Santa Fe for eight hundred dollars.

“I thought more people would be here. It’s Monday.” Heather placed a hand over her perfectly made‑up eyes and peered off toward a row of trailers. She had found a housekeeper who could also do her makeup. She loved telling people this, like it was somehow exceptional. “I’m going to see if I can find anyone to ask about lessons. You can stay with the horses, if you want.”

Maple could tell that her mother wanted her to want to stay with the horses, so she nodded and dragged their enormous bag of carrots toward another barn.

*

Maple stepped into the cool shade of the breezeway. The horses stuck their heads over the doors and watched her. One noticed the carrots and whinnied. Then they all started whinnying, pacing around their stalls and tossing their heads. One even bucked and cantered a tight circle. They were freaking out. It was kind of scary. Maple had a sense, always, that something terrible was about to happen now. Right now. She called it prophecy; her therapist called it generalized anxiety disorder.

“What are you doing?” A girl slipped out of a stall and into the aisleway.

She seemed older than Maple, but she was small and delicate. She was wearing a bright red coat, like a girl marked for death in a horror movie. But she had the face of the killer.

“You can’t be here,” the girl continued. “Didn’t you read the signs?” She noticed the carrots. “Oh my God! Are you giving the horses carrots? Don’t you know you can’t do that? They could have Cushing’s disease. Or bite you. I know this girl, and her mom got her finger bitten off by their horse, and the horse swallowed it. Seriously, I’m not fucking kidding.”

Maple dropped the heavy bag on the ground. Her whole face burned. She wanted to run, but her legs felt weak. She was dizzy. She wished her mom were there.

Heather never seemed to be bothered by drama. In fact, she often seemed drawn to it. If there was a kerfuffle at a restaurant, if gunshots rang out, Heather drifted steadily toward it, clutching her purse and smiling benignly. Can I help?

“My mom—,” Maple started.

“You need to leave,” the girl said. “Seriously, you’re actually trespassing. And why are you wearing riding clothes? It’s Monday.”

Maple burned up even more. She’d tried to warn her mother about this, when she had dressed Maple up like a doll.

A woman who must have been the other girl’s mom appeared.

She shared her daughter’s red hair.

“What are you doing here?” she said. She also shared her attitude. “My mom’s here,” Maple said, not answering the question. “I have to go get her.” She took off like a lunatic toward the offices. She abandoned the carrots in the barn aisle.

“Hey!” the girl yelled after her. “You can’t run around horses!”

*

Maple found her mom practically in the middle of breaking and entering. It would never have occurred to Heather that the office wasn’t hers to open.

“Why are you running?” Heather asked, trying a combination on the lock. “I was thinking I could write them a note. I think this is the main office. I’ve already left seven voice messages.”

Heather had been trying to contact this barn since before the move. Instead of giving up, she got only more determined.

Maple was breathing hard. She was on the verge of tears. “They said we can’t be here!” Her voice rose precipitously. “They said we’re trespassing.”

Heather perked up. “Who said that? Is someone here?”

Heather started in the direction Maple had come from, but then the red‑haired woman appeared, matching daughter in tow. When she saw Heather, she smiled so fast it was like a quick draw in a shoot‑out.

“Why, hello there!” Her eyes ran fast over Heather, like she was calculating the value of everything she saw—Heather herself included. “I’m Pamela and this is my daughter, Vida.”

“I’m Heather. Parker. And this is my daughter Maple.”

“I was just telling your sweet girl that unfortunately this barn isn’t open to the public.” Pamela was holding Vida’s hand, their fingers laced, like they were best friends instead of mother and daughter.

“Oh, we’re not the public,” Heather said. They had been rich for a short amount of time, but Heather had adjusted beautifully. “We’re here to sign up for riding lessons.”

“It’s Monday,” Pamela said. “No one comes in on Mondays. And this isn’t a lesson barn. They don’t have school ponies or summer camps.”

Heather stepped forward, crossed her arms neatly. Since she had become rich, Maple’s mother had changed, although not completely. The root of what she had always been was still there. But she had become more herself.

“We just bought a house a mile from here,” Heather said, as if that had anything to do with it.

But Maple could see Pamela’s expression change. It softened a little, like the Parkers were closer to belonging not just there but everywhere.

“How lovely! That makes us neighbors,” she said. “But I will warn you, this probably isn’t the barn for you.”

Maple knew the woman couldn’t have tempted her mother more. “There’s a good riding school in Olivenhain. I can give you their number.”

“No, thank you. I like this one. It’s closer to our house. I want Maple to be able to walk to the barn if she wants to,” Heather said. As if Maple would ever walk a mile. “Would you mind taking my number? Then you can pass it along to the owners for me. I’ve been trying to reach them.”

“Kieran Flynn,” Pamela said, like the name meant something to everyone. “He’s the owner and the head trainer.”

Pamela clearly didn’t want to take her number, but Heather just waited. Pamela finally took out her phone. She typed Heather’s number in quickly.

Then she added, “This is a show barn. Last year, we outperformed every barn at the Southern California International Horse Show. We demand total commitment to the program. We’re a very tight community. You have to have your own horses, and your horses have to be in the training program. That means all of your rides are supervised by a trainer, and your horse is schooled by a Professional rider. It’s really not a place for fun.”

“Good,” Heather said, taking Maple’s hand like she was aping Pamela. “We don’t want to have fun.”

Heather grinned. There was nothing she loved more than the word no.

__________________________________