I’d never been to an advance screening. The closest I’d come to seeing a movie before it was officially released was the summer of 1990. I was fourteen, and my mother had taken a day off work so we could see Die Hard 2. No one was in the theater, so I imagined we’d been given exclusive tickets to a private showing with our choice of seats. I propped my sneaker-clad feet up on the empty seat in front of me, windshield wiping back them and forth in excitement—whether for the movie or the imagined exclusive premiere, I still can’t be sure.

Imagine my exhilaration when twenty-eight years later, my inbox chimed with an invitation to an actual advance screening—and not for just any movie. I’d been asked to attend a showing of Marvel Studios’ Black Panther and, better still, I’d get to talk about my experience on the radio.

Months earlier, not long after news broke that Marvel’s first African superhero would get his own solo film, and after I’d watched every iteration of the trailer countless times, I’d written an essay about my love for comics, and in particular my excitement about the upcoming film. The piece centered on the idea of removing the notion that characters of color are only fit to be sidekicks. The ever-increasing hype for the film gave me hope for people of marginalized communities to see ourselves represented on the screen in a positive manner, absent of stereotypes, with the support of a studio responsible for global blockbusters.

Even with all that hope, I still wasn’t ready for what I saw.

Ryan Coogler’s film tackled issues both internal and external to the Black community—the damage done by the ravages of colonialism ran parallel to the notion that an advanced nation would rather keep their existence a secret than provide aid to their brothers and sisters suffering in other parts of the world; that the once-king of Wakanda would murder his own brother, leaving his nephew childless—and thereby radicalizing him to “villainy”—to maintain that subterfuge. Subtle shots were taken at Trump’s vitriol regarding immigration. T’Challa’s kingdom maintained a “Wakanda First” policy to tragic results.

Heady stuff for a superhero movie—and yet the medium of comics has almost always tread this ground, and powerfully.

In many ways, it’s what drew me to comics, first as a child, and again as an adult. Much has been said by those in the know about the X-Men and how the title served as a metaphor for the American civil rights movement, but for a young mixed-race boy growing up in this country, it held an appeal for me that I’m not sure I was fully cognizant of at the time.

I was a straight-haired, brown-skinned boy who didn’t talk in any of the ways anyone expected me to talk, didn’t dress in the clothes I was expected to wear, yet from an early age I was expected to answer that question many like me know far too well: What are you?

Who among us wouldn’t find comfort in super-powered mutants who use what makes them different to fight ignorance, bigotry, and oppression?

That these stories had such a profound impact on me made me want to write stories of my own—stories that would speak to those who felt alone in being different because of the color of their skin or who they were supposed to love. It’s the reason comic books play such an important role for the main character in my novel. In some ways, it is my way of saying thank you—an homage of sorts to the words and images that made me feel less alone as a child and have inspired me to continue to address issues of social justice on the page.

In that vein, here are just a few graphic novels that have impacted me in one way or another. Perhaps they’ll have a similar impact on you.

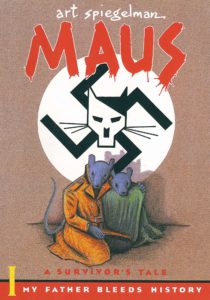

Maus, by Art Spiegelman

Art Spiegelman’s masterpiece was one of the first graphic novels I owned. While the Nazis were represented by cats and the Jewish people by mice, there was no metaphor to be deciphered here. The anthropomorphizing did nothing to detract from the power of Spiegelman’s narrative. It’s the first publication in the comic medium that I can remember that tackled the issue at hand head-on and not through allegory. The discomfort I felt reading it sticks with me today.

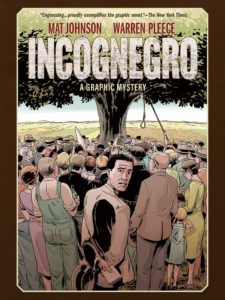

Incognegro, by Mat Johnson

Though I discovered him as a writer only recently, Mat Johnson’s Loving Day is one of my favorite books, tackling the struggles of mixed-race characters with humor and heart. I was excited to discover he had written a passing-narrative graphic novel just in time for its reissue in hardcover. It’s a raw exploration of identity and racial violence and defies you to put it down.

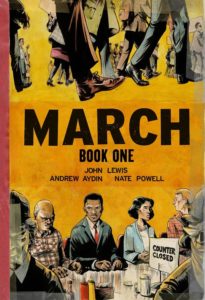

March, by John Lewis

While X-Men symbolized the struggle for civil rights in America, Representative John Lewis’s March trilogy chronicled the real story of one the movement’s heroes. The series is beautifully written, the art both inspiring and unsettling, and its importance did not go unnoticed. The series won multiple Eisner awards and Book 3 was the first graphic novel to win the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature.

V for Vendetta, by Alan Moore

Though not specifically dealing with issues of race, I was fascinated by Alan Moore’s choice never to reveal V. There is a sequence in the book that demonstrates that all genders, races, and sexual orientations could be the one behind the mask. It conveyed quite powerfully that the struggle against an oppressive government was everyone’s to share, and that there was an indomitable strength to be had in that realization.

Saga, by Brian K. Vaughan

Two alien races are at war, yet a man and a woman from each side meet, fall in love, and have a child. Drawing distinct parallels to the pre-Loving vs. Virginia era and sometimes narrated by the pair’s mixed-race daughter, the graphic novels tackle ideas of miscegenation and class warfare with incisive humor and vividly imagined worlds, creatures, and characters.