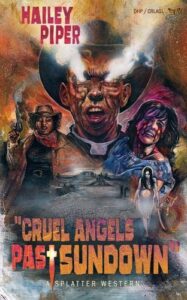

\Horror and religion might sound like opposites at first glance. Most horror fans can probably think of at least one grisly film called out by a faith-based group (usually a sect of a certain religion). But as observed by Richie Tozier in Stephen King’s It, there’s a lot of horror within religious texts, too. And there can be religion/faith in horror texts. That was my perspective when writing my recent novel Cruel Angels Past Sundown, a horror + western mash-up that also draws in Biblical horror on a cosmic scale, exploring concepts of “might makes right” and questioning the conceit of what rightness and goodness mean in a judgmental system.

It’s nowhere near the first tale to craft a faith-and-fear sandwich. There are classics like Rosemary’s Baby by Ira Levin, more recent books like Adam Nevill’s The Ritual, and much more. Any list will only scratch the surface, and I want to take care when there are hundreds of faiths versus labeling a book like, for example, Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance a horror novel even when events within are profoundly horrifying.

But below I’ve set out seven titles I very much recommend:

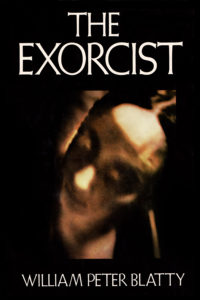

The Exorcist by William Peter Blatty

Starting with a classic, this one’s over fifty years old, but I only (finally) read it this summer. The movie has been more familiar to me. Each cinematic glimpse is a fuller interaction within the book, and that’s true for the horror and faith, too. While both book and film show the exhaustive medical attention given to understanding Regan McNeil’s condition, I appreciate that Catholic priest Father Karras, in wrestling with his faith, scrutinizes every psychological and mental angle before turning to exorcism, even butting heads with faith, and then weighing what he can explain versus what he can’t. If you’ve only seen the movie, you’re missing out on an eloquent, intelligent, and heartbreaking novel.

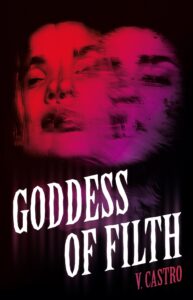

Goddess of Filth by V. Castro

What better way to follow a cornerstone of possession and exorcism fiction than with a table-flip on the whole premise? Lourdes, Fernanda, and their friends conduct a séance one quiet summer night, only for Fernanda to take on strange behavior such as cutting herself, speaking in Nahuatl, and more. Local priest Father Moreno believes there’s a demon inside Fernanda, but her possession challenges the notions of what is truly demonic in this world. It’s a captivating turn on assumptions, examining cultural differences and questioning who has the right to claim righteousness when one faith has been the bludgeon to erase another while colonizing many lands and peoples.

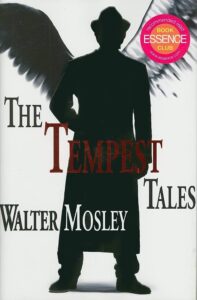

The Tempest Tales by Walter Mosley

After his murder by a cop, Tempest Landry’s soul appears before St. Peter, who determines Tempest belongs to hell. But Tempest refuses to go, even against the devil’s behest, challenging the premise of simple morality when societal workings force a more complex understanding. Not everyone starts from the same place, and Tempest’s return to Earth in another body and with spiritual observers desperate to guide or take him only emphasize how people are tossed around by life.

The Long Shalom by Zachary Rosenberg

Alan Aldenberg is a former member of the Jewish mob-turned-private detective drawn into a horror story of missing people, inhuman forces, and a grim unreality reaching across time. It’s noir-meets-horror brawler of a book. Also, it’s a distinctly Jewish look at cosmic horror as both a cycle of violence and a threat to identity. Religion isn’t simple here. It’s part of an intersection of language, culture, faith, and significance in which the history of a people is the only thing stopping an unearthly malevolence.

Infidel by Pornsak Pichetshote, Aaron Campbell

Yes, I’m including a graphic novel, deal with it. Infidel is a visceral exploration of outsider-ness and who decides who’s in or out, examining prejudice both through an apartment building’s tenants and a vicious presence that feeds off hateful thoughts and feelings. The weight of hatred is both emotional and physical here, an almost inescapable manifestation. Also, the art is striking, scary, and gorgeous.

Little Eve by Catriona Ward

Little Eve by Catriona Ward

The titular Eve lives in a crumbling stone house off the coast of a small town, where she and her small family live by Uncle’s strict and bizarre rule, preparing them for a seaborne apocalypse. He’s the focus of the book’s faith. As vessel for the terrifying “Adder,” he controls the family down to whether they eat, sleep, speak, or exist in each other’s eyes. Like most of Ward’s books, Little Eve will have you asking “What the hell is really going on?” in delight shortly after starting and all the way to the end.

“Solve for X” by Stephen Graham Jones

Some short stories stick with you because you want them to; others cling with the bite of cold duct tape and don’t give you a choice. That’s “Solve for X,” maybe the most brutal story in the Stephen Graham Jones collection After the People Lights Have Gone Off. At first it appears to be a simple tale of an abducted woman and her strange tormenter. But as the story develops, it opens into a bloody exploration of conditioning and faith, and whether the belief in creation can influence the universe into genuine manifestation beyond the wounded flesh. The formation of power in belief doesn’t have to be a world-spanning organization; it can be two people and the miraculous horror between them. I read this years ago and still can’t get it out of my head. I probably never will. Maybe you won’t, either.

***