It was twenty years ago today, when Hannibal feasted on matter gray. He’d been hiding out in Italy, until he gutted a cop with glee. He and Clarice would later dine, after escaping the angry swine. Thomas Harris re-introduced to you, Dr. Lecter’s Starving Book Club Fans…

___________________________________

On June 8, 1999, after a long barren sojourn in the literary wilderness, Thomas Harris finally delivered his third book featuring a psychopathic psychiatrist with a taste for green oysters from the Gironde and the sweetbreads from a former flutist of the Baltimore Philharmonic Orchestra.

Dr. Hannibal Lecter was back.

So, of course, was FBI agent Starling, but let’s be honest, there’s a reason the book’s title isn’t Clarice. Eighteen years after his first appearance as a bit player in Red Dragon, Lecter had become a cultural sensation, bigger than the 29 lives he ultimately took, and the absence of bloody malice since 1988’s sequel to Red Dragon, The Silence of the Lambs, had horror lovers everywhere chomping at the bit. The deranged plot was treated like a state secret, lest word leak out that some poor random redneck deer hunter would become sacrificial Starling bait after taking a crossbow to the dome and having his mutilated body left splayed out in the “Blood Eagle” position. (Feel free to look that up on your own.)

Carole Baron was the publisher and editor of Hannibal at Dell/Delacorte. She didn’t recall a lot about the process, but one detail about the covert operations stuck with her. “Once we got the manuscript in, we kept it close and made sure to publish it within a few months, so that it didn’t get pre released to a waiting readership. Everyone got to read it at the same time: the publication of the hardcover.”

The pre-publication build-up was insane. The initial pre-print run was originally 1-million copies, but it was raised to 1.5-million as the return of Dr. Lecter reached a fever pitch. By June 2000, 1.7-million hardback copies sold. (Five years later, there would be some 4-million paperbacks in print.) It wasn’t just stateside either, it would go on to become the fastest-selling fiction hardback seller in U.K. history, adding another million to the total. Chris Nashawaty, a former Entertainment Weekly film critic who wrote a May 1999 Hannibal cover story, noted how the masses were jonesing for their cannibal fix:

Copies of Hannibal were locked away in safes. Confidentiality agreements were signed by the few souls lucky enough to see the manuscript. Rival publishers shooed their big releases out of harm’s way. Studio heads foamed at the mouth. And booksellers cleared their shelves for the novel’s delivery date.

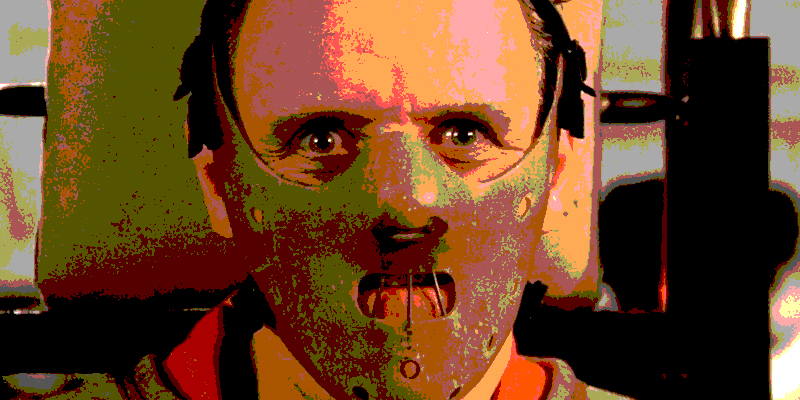

“It was rare at the time for EW to do cover stories about books and publishing, but the curiosity about Hannibal was massive at the time, and not just for our readers, but for Hollywood as well,” says Nashawaty (who has a book out of his own about a movie filled with scary creatures of a different sort, Caddyshack.). “Harris created one of the great bogeymen in literature, which is no small feat. I devoured the book, but it was a different reading experience because Anthony Hopkins became Lecter. Hannibal the film didn’t come out until 2001, but we still featured Hopkins in his Silence of the Lambs mask on the front of EW because a book jacket doesn’t make for a very sexy cover.”

***

It had been eleven years since Silence of the Lambs was published and eight since the film was released. The movie was an enormous commercial and critical hit, spending 26 weeks atop the box office, bringing in $273-million worldwide and becoming one of only three “Big Five” Oscar-winning pictures in cinema history. Jonathan Demme’s film is a classic, in the top five of AFI’s “100 Most Thrilling American Films,” and as re-watchable as they come (Michael Mann’s criminally-underappreciated 1986 Red Dragon adaptation, Manhunter, should be too.) The lengthy Lecter layoff raised the expectations on Hannibal, both the novel and the movie everyone knew would follow, beyond the pale. The pressure on Harris to deliver was enormous, especially considering he never conceived it as a trilogy—Red Dragon and Silence of the Lambs are mostly singular narratives independent of one another. Fortunately for Harris, an early review in the all-important New York Times was a five-star rave from one of the few people on the planet who could match him in both popularity and dismemberment.

In the Sunday Book Review, Stephen King said Hannibal was better than its predecessors, calling it “one of the two most frightening popular novels of our time” along with William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist. And then the King of Horror really got down to fawning, labeling Dr. Lecter “the great fictional monster of our time,” namechecking Tom Wolfe and Bram Stoker, and begging Harris not to wait so long before delivering another book.

In the Sunday Book Review, Stephen King said Hannibal was better than its predecessors, calling it “one of the two most frightening popular novels of our time” along with William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist. And then the King of Horror really got down to fawning, labeling Dr. Lecter “the great fictional monster of our time,” namechecking Tom Wolfe and Bram Stoker, and begging Harris not to wait so long before delivering another book.

King wasn’t alone in his praise, but Hannibal, unlike its titular character, wasn’t a stone-cold killer. Critics were mixed at best and there were plenty of dissenters, including Christopher Lehmann-Haupt in the Times three days prior. He zeroed in on the “overwrought plot” and the dumbing down of Dr. Lecter with the amusing kicker “Bring on the noisy lambs, then. They might as well be roaring.” But at least Lehmann-Haupt had some nice things to say. In Talk, former fan Martin Amis sliced-and-diced the novel, piercing a literary blade into the author’s heart with “Harris has become a serial murderer of English sentences, and Hannibal is a necropolis of prose.”

Given the gift of time, however, it may be the middling unstarred Kirkus Review that best captures the book and its place in the waning days of the 20th-century ether. Hannibal is compared straight up to that summer’s other major cultural rejuvenation, The Phantom Menace. It highlights the book’s provocative baroque approach and audacious epilogue while also laying out the hard truth that the “monstrous Dr. Hannibal Lecter” is “a brand name as reliable as the Jedi Knights.”

(If only Jar Jar Binks had been eaten alive from the inside by a Moray Eel… Now you’re talking.)

Two decades on, the novel Hannibal hasn’t particularly grown in stature, but the character of Dr. Lecter lives on. The American Dracula may already have achieved immortality; the well-received NBC show adapted from Harris’ works is currently streaming on Amazon Prime and has a devoted fan base who call themselves “Fannibals.” As a stand-alone attempted work of art, though, Hannibal feels like an afterthought. Stephen King aside, it doesn’t have the literary standing of its forefathers.

“I greatly admire Harris’s work, but am rather more drawn to Red Dragon and The Silence of the Lambs. While totally gripping, I was disappointed by Hannibal. Partly, I have to admit, because they are more focused on interesting detectives,” says Mark Jancovich, professor of Art, Media, and American Studies at the University of East Anglia (U.K.) and the editor of the bi-yearly Horror Studies Journal.

He goes on to say that “the focus on Lecter creates problems as it is precisely his unknowability in the other novels which is key—He taunts Clarice about the blunt tools that she uses to ‘explain’ him, and refuses ‘explanation.’ How do you tell a story from the perspective of someone whose head we can’t get into; which, inevitably leads to a tendency to explain and understand? Hell, the novel even ends up resolving Lecter. You can’t unbreak things but he seems to waltz off with Clarice as a kind of resolution or at least sense of completion…”

Hannibal’s controversial ending divided Harris’s fans (myself included), because it was felt he sold Clarice Starling down the river. Quick refresher course: Under heavy sedation, Starling becomes a cannibal after eating bits of her jerk boss’s brains, offers her naked breast to Dr. Lecter (as a replacement for the one his beloved sister Mischa suckled upon before later being eaten by Nazis in a soup… stay with me), and then they fall madly for one another and live happily ever after in Argentina, sipping champagne at the opera and making sweet passionate love in the afternoon. Or, as Harris writes, “Their relationship has a great deal to do with the penetration of Clarice Starling, which she avidly welcomes and encourages.” Who says romance is dead?

***

Upon publication, Hannibal was overshadowed by the phenomenon surrounding the book, but re-reading all these years later, I found myself fascinated by how deeply committed Harris was in going for broke. Grandiose plotting that once angered me—like having Lecter suffer the indignity of flying coach while wearing a Toronto Maple Leafs jersey—I now find more of a glorious broad-gauged mess rather than a betrayal. Making the deaths more and more macabre, having a character slice off his own face and feed it to the house dogs from hell, will always appeal to lovers of gore, but that was the easy part. Ditching the police procedural format for a wild 544-page continual-one-upmanship-of-ones-own-work that concludes with the one ending nobody saw coming because, pardon my French, it’s batshit fucking crazy, is daring and admirable in its own right.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but there is no active cannibalism in Silence of the Lambs. Yes, Lecter rips flesh off the face of a doomed Memphis cop with his teeth, but that was part of his escape plan, not a proper meal. He mentions his culinary habit twice, first famously saying he ate the liver of a census taker with “fava beans and a nice Chianti” (film only, in the book its “big Amarone,” a higher-faluting Italian wine made from air-dried grapes… doesn’t matter, both vintages were suppose to be part of an inside joke about Lecter being off his meds.) And the film ends with Lecter telling Starling he won’t be coming for her, but he has to hang up the phone now with the perfect chiller, “I’m having an old friend for dinner,” as he watches his former psychiatric hospital tormentor Dr. Chilton disembark from a plane. It was a change from the original script ending, where Chilton was about to be filleted, which would’ve left a lot less to the imagination—like its successors, book and film, to come.

Personally, I like to think Harris at least partly ups-the-grotesque-ante in Hannibal to rub our collective noses in our collective love for a serial killer—noses being just one of the multitudes of body parts gnawed upon by animals, human and otherwise, throughout the book. Or maybe Harris knew another straight-forward thriller wouldn’t cut it, so he had no choice but to go Grand Guignol on his readers, or both. In Silence of the Lambs, the relationship grows between Lecter and Starling because they need one another. She’s trying to save a Senator’s daughter from having Buffalo Bill turn her epidermis into evening wear; He’s angling to get moved to a less-secure facility that will lead to freedom. Harris wrote Hannibal from a totally different realm of authorial celebrity. Lecter and Starling had become pop culture icons on the page and screen, so it’s understandable why he went whole hog—whole ravenous bloodthirsty limb-from-human-limb hogs as it would turn out—on the butchery and shifted from detective stories featuring flawed-but-decent protagonists to a Gothic horror tale with a fussy intellectual madman—Masterpiece Theater Patrick Bateman if you will—as its main character.

Or maybe the dude just enjoyed spending the better part of a decade dreaming up gruesome cannibalistic death scenarios. Whatever the case, the novel Hannibal is rife with stomach-turning depictions of sentient characters being consumed. Be it by pig, eel, Nazi, or climatically, sauteed with brown butter sauce, shallots, and caper berries, dredged in fresh brioche crumbs, and served with truffles and a “splendid white Burgundy” to virgin anthropophagite Clarice Starling, a lot of characters done got ate.

“I don’t know if it was a case of Harris giving the public what he thought they wanted, or whether it is less conscious than that, but the Lecter of Hannibal seems to be different from the Lecter of the earlier books, much more like Anthony Hopkins’s version,” says Jancovich. “Harris’s original Lecter is detached and precise, and doesn’t need the leering menace that Hopkins suggests. I think Harris might just have wanted to finish Lecter off like Arthur Conan Doyle tried with Sherlock Holmes, but there’s also the sense he might have been under huge pressure by the publishers. It’s not really clear what the impetus for the book is, other than the obvious commercial one.”

Harris clearly wanted to differentiate Hannibal from Red Dragon and Silence of the Lambs and boy did he ever, but did he have a choice? It’s near impossible to read Lecter on the page without hearing Hopkins’ voice, which had been parodied everywhere by the time the good doctor made his triumphant return. You yourself could probably roll a “Clarrriiicceeee…” off the tongue should the appropriate moment present itself, like, say, Easter dinner. One of the most sophisticated demons of modern letters morphed into Jason Voorhees with better taste. In a “Forgotbusters” essay at the dearly departed The Dissolve, writer Nathan Rabin nailed what Harris was up against in reanimating the beast:

Silence Of The Lambs made Hannibal Lecter an insanely lucrative name destined to make the money hairs on studio executives’ necks go woo-woo- woo, but it also made him a joke. When Billy Crystal was wheeled out by “orderlies” at the beginning of the Academy Awards in 1992—where the film triumphed in many of the major awards—wearing a replica of Lecter’s famous mask, it was the year’s most obvious joke. And like most obvious jokes delivered by Crystal, it was rapturously received, even as it pointed out just how defanged and comic the famous villain had become.

(No thanks to Rabin, I am also now aware a Dom DeLouise “stabbing satire,” Silence of the Hams exists. The clip within is far more horrifying than the facial Puppy Chow scene in Hannibal.)

Hopkins is Lecter, Lecter is Hopkins, two sides of the same Spyderco, both ferociously popular. In the summer of 1999, Hannibal spent four months on the New York Times bestseller list, reaching the top slot on June 27th and staying there until mid-August. (Amazingly, it was second on the hardcover fiction list at year’s-end behind John Grisham’s The Testament. Apparently everyone was allaying their Y2K fears with a good book.) Hannibal was huge and given its pedigree, destined for the Hollywood treatment before it was even published. Prolific Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis bought the film rights for $10-million prior to the book’s release, so mixed literary reviews or not, the movie was getting made.

Harris sent copies to Jodie Foster and Jonathan Demme with the expectation that they would get the band back together and make another Academy-Award winning blockbuster. It didn’t work out that way. Demme bailed because he found the book lurid; Foster took a higher road saying she was doing another movie, Flora Plum, which was never made. Later, in a 2005 interview with Total Film, Foster made it clear there was more to it, saying she and Demme didn’t want to “trample” on Starling, and whispering that she saw Hannibal but had no comment.

The only familiar Silence of the Lambs face was of course, Frankie Faison, who played hospital orderly Barney Matthews, the guy who introduced the original Clarice to that other returning fella in the Baltimore Nut House. Considering how Starling gets shunted to the side for huge chunks on Hannibal, having Hopkins back was really all that mattered. Pairing Hopkins with Julianne Moore, one of the finest actors of the last thirty years, offered a glimpse of hope that the movie version could make its lunatic source material work on the big screen. It did not. It was a hit no doubt about it, earning $350-million worldwide, but it was gleefully roasted by critics like Slate’s David Edelstein who called Hannibal “simply a fat slab of sadism.”

The film is amorally decadent, gross without being scary, depraved without being humane, and strangely campy, in a way that bloodthirsty scenes end up being downright silly. There’s a wink-wink to the audience that “isn’t it funny we’ve all joined in communion to root for a man who craves the taste of your neighbor’s organ meat?” A prime example: The disgusting scene where Lecter disembowels the Italian detective over a piazza in Florence and all of his guts splatter on the cobblestones, is punctuated with a cartoonish plopping sound—the vicious public murder has all the seriousness of a Wile E. Coyote losing to his arch-nemesis, the cliff. Pinch-hitting veteran director Ridley Scott knows how to do intimate horror like in Alien, and grand spectacle like Gladiator, but whatever he was going for overall in Hannibal doesn’t work.

“I remember seeing an advance screening and being pretty let down,” says Nashawaty. “It’s hard to capture lightning in a bottle a second time—especially without Jodie Foster. Minus her as Clarice, it all felt…wrong. Though the dinner scene where Ray Liotta gets served his own brains is still a honey.”

Except therein lies the film’s biggest weakness. It doesn’t have the courage of Harris’s bonkers Hannibal convictions. The author went all-in; the filmmakers pull their punches. Clarice Starling never nibbles on Henry Hill’s frontal lobe, nor does she end up waltzing in the moonlight with the flesh-devouring devil she knows. And loves, daily.

Instead, the audience is asked to believe Hannibal Lecter cleaved off part of his hand, at least a thumb, to get out of Starling’s handcuffs, cauterized the wound, bandaged it, then took the time—as the police were swarming in—to cut up some more pieces of brain, save them in a Tupperware container, disappear into the woods, and heal up fast enough to be on a plane where said cerebrum remained edible enough to be enjoyed in-flight with foie gras and vino, and to be shared with a fellow passenger who looks to be in fifth-grade. For Clarice’s sake, Hannibal didn’t even don the damn hockey sweater.

Dr. Lecter would go on to become even more of a commodity than a character. By 2016, Anthony Hopkins was admitting he wishes he’d given up the ghost after Silence of the Lambs. It’s never been topped and will never be topped, and the Lecter universe has been one of diminishing returns since Hannibal was published. The Red Dragon reboot was a pale facsimile of Manhunter and head-to-head Brian Cox was better than Hopkins. And I have to come clean—up until very recently, I had no idea Thomas Harris wrote a Lecter prequel, Hannibal Rising, or that he penned the screenplay for what sounds like a truly terrible movie. (De Laurentiis reportedly strong-armed him into it.) Unfortunately, it seems like his those will be his last words on Lecter. In May, 78-year-old Harris gave his first interview in more than forty years to promote his new book, Cari Mora, the first in thirteen years. It’s set in Miami and his most famous creation is nowhere to be seen.

If Thomas Harris has finally devoured Dr. Lecter, it was a hell of a run, punctuated by the madness surrounding the publication of Hannibal. There is no way to separate the character from his namesake book, and Silence of the Lambs will always get top billing, but Hannibal—the novel, at least—still provokes arguments all these years later. Fans divided over unhinged storytelling in Hannibal is the book’s legacy, it means his revered cannibal matters. Although true believers, Thomas Harris might not be done just yet. He suggested in the recent New York Times profile that he sometimes wonders what Hannibal is up to…

Perhaps, one last time, Harris should have his old friend for dinner.