Road Runner & Coyote Law #3: “The Coyote could stop anytime—if he were not a fanatic.”

Open on a southwest desert vista, desolate but for a harmless Road Runner. (Beep, beep.) We zoom out, revealing a suspiciously ticking package behind the unsuspecting creature. Another zoom out, this time introducing a Coyote (Wile E.) frantically pressing a button on his phone marked “Detonate.” The package ticks on undisturbed, and an increasingly distressed Coyote calls Bomb Customer Service. Such a thing exists in this cartoon world, and as the call goes through, the package finally serves its purpose, leaving the Road Runner unharmed but covering our Coyote in ash and soot.

Though this exact scene never played out in any of the classic cartoons starring this duo, its comedic grammar should be familiar to anyone whose youthful Saturday mornings orbited around whichever TV was showing Looney Tunes. But if you swap out the Coyote for SNL legend Bill Hader and flip the Road Runner for a houseful of Bolivian mobsters, then you’ve got a scene lifted directly from Barry—HBO’s preeminent “black comedy crime drama” (per Wikipedia) that splits the difference between hitmen and Hanna-Barbera. And if you’re not familiar with Barry—or didn’t stick around long enough to see that explosive third-season moment—it’s likely because of that tricky tonal balancing act.

Barry’s original logline was simple but hooky: a weary assassin tails his target to a low-rent acting class, where the acting bug bites him hard enough for him to see it as a door to another life (despite his obvious lack of dramatic talent). The meta proposition of watching Hader, who famously dreaded the very anxiety-inducing national stage on which he excelled, grapple with hating the thing he’s best at and sucking at what he loves was intriguing enough on its own.

The fact that it was also pitched as his first major post-SNL brainchild and promised to bring his impressionistic (in both senses of the word) comedy and goofy sensibilities to the wild world of wetwork only added to the intrigue. And from the jump, Barry delivered on that promise.

The problem, to certain viewers, was that it over-delivered on its unspoken promise to treat the profession of assassination with the heightened realism that powers any great impression. While caricaturish exaggeration plays for laughs when the target being lampooned is LA’s amateur acting scene, exaggerating violence means more violence. The lunacy inherent to such an extreme(ly dark) corner of the world gets stretched and magnified so we can marvel at its madness, but its darkness gets magnified too, threatening to swallow Barry’s characters and viewers alike in its gaping maw.

Barry dissects that assumption with the sobering reality that anyone willing and able to be a hitman in the first place would necessarily contain a darkness that could never be subdued by the light of actingThe most surprising thing about Barry is not how dark it gets, but that its comic goofiness keeps steady pace with its bleakness. Even in its pitch-black later seasons, there are still baristas influencing entire towns with their therapeutic insight, criminal empires meeting at Dave & Busters, and Sy Ablemans staging Zoolander-esque break-ins. Of course, scattered between those gags are mass killings, freeway motorcycle shootouts, and increasingly abusive relationships.

These emotional juxtapositions feel disjointed at first, but as the show slowly wins you over to its idiosyncratic wavelength, they begin to coalesce as two complementary halves of one twisted bicameral mind. By the end, sometimes even the humorless bits are so comically dark that you can’t help but laugh in self-defense, a thin shield against the brutality of a show that’s constantly willing to go there.

While reconciling the Looney Tunes-worthy hijinks with this ever-darkening night of the soul can be a wrestling match at times, it’s this very tension that provides Barry’s dramatic locomotion. It also doubles as a macrocosm of Barry’s paradoxical grapple with reality, as he tries to forcefit the most unforgivable parts of his life into a redemptive container, no matter who he has to kill to make it work.

The humor of the logline relies on the assumption that this scary hitman is really a big goof at heart, and the magic of acting will save the day! Instead, Barry dissects that assumption with the sobering reality that anyone willing and able to be a hitman in the first place would necessarily contain a darkness that could never be subdued by the light of acting—and in fact, could easily swallow that light (and all others) in its attempt to capture it.

We can see this as clearly as we can see how Wile E.’s plans will inevitably backfire, but Barry’s as clueless as the Coyote. Tragically (and often, hilariously), so are the many characters snagged in his undertow, and we have to watch as their struggles toward the light are snuffed out by his contagious self-sabotage. All it takes to get there are some gags that could make Bugs Bunny blush.

Chuck Jones and the other cartoonists behind the original Road Runner and Coyote adventures lived by a set of self-imposed laws that governed the adversaries’ actions, many of which can be mapped directly onto Barry’s more visceral exploits. But one telling difference between Looney Tunes’ Road Runner/Coyote scenario and Barry’s: in Barry, the mobsters don’t end up unharmed, but as a pile of bodies on the pile of bodies Barry leaves in his unassuming wake.

Road Runner & Coyote Law #2: “No outside force can harm the Coyote—only his own ineptitude or the failure of the Acme products.”

True to its cartoon bona fides, Barry’s violence never strikes without dramatic cause and effect. If the cartoon were just about the Coyote getting clobbered by the Road Runner’s trap, it’d be gratuitous carnage, but it cleverly focused on the Coyote’s foolery trapping himself through an elaborate Rube Goldberg’s machine of own-goals. “A hits B” is barely a sentence, but “A outwits B into tripping over his own overextended attempts to hit A” approaches poetry.

So it is in Barry, whose every self-sabotaging action is crafted with narrative and visual intent. We first meet our titular killer as he’s impassively wrapping up a hit in a nondescript hotel room. It’s immediately clear that the work—done at the behest of his cantankerous handler/father figure, Monroe Fuches (Stephen Root)—is as easy for him as it is soul-crushing, though more from unfulfillment than guilt. It’s not a crisis of morality but of inertia that inspires him to change vocations.

When he stumbles his way into disgraced actor Gene Cousineau’s (Henry Winkler) acting class, Barry’s struck by the liberating messiness with which the hardly professional students approach their art. Compared to the cold remove from which he enacts his killings, here’s something that offers a full emotive experience with none of the inconvenient body-baggage. Of course, it’s as clear to us as it isn’t to Barry that the jump from one world to another is practically unbridgeable, a fact that gets hammered home by the end of the pilot when Barry is involved in the murder of both his acting class colleague target and some of the Chechen mobsters who wanted him dead in the first place. Before he can take the first step down it, his path to redemption is latticed in crime-scene tape, his escape hatch slammed shut.

Try telling that to him, though. The same ruthless determination that makes Barry such an effectively cold-blooded killer allows him to put up whatever blinders are necessary to justify the single-minded pursuit of his new passion—for acting glory, and for his acting classmate, Sally Reed (Sarah Goldberg). This Chechen mob business and its bloody intersection with Gene’s class is the inciting event of the entire series, simultaneously acting as the pre-emptive nail in the coffin for Barry’s stage dreams and the primary motivator for his impossible mission to pursue them.

Unlike Wile E. Coyote’s ineptitude, it’s Barry’s merciless aptitude for doing—and justifying—whatever it takes to keep his acting dreams alive that perpetuates his downfall. Barry’s problem isn’t that he can’t kill the Road Runner, but that he can and does kill any vermin standing between himself and Sally and Gene’s world. And while he convinces himself that his actions constitute a necessary path-clearing en route to righteousness, the delusion necessary to prop up that justification builds to perilously comical heights. Tension, locomotion. All building, as any great Road Runner cartoon does, to an inevitable cliff.

Or, possibly, blowing right past it. By the time Barry’s murderous misadventures put him in a car with the innocent Marine buddy Barry implicated in his various crimes along the way, he can’t even see the path he took to get there, nor how it could possibly be his fault that he’s now forced to choose between killing his friend or never acting outside of a jailhouse again. When his friend admits that he’ll have to come clean, Barry’s response is to scream, “WHY DID YOU JUST SAY THAT?!” – pointing the finger (and the gun) anywhere but inward. The camera elegantly cuts to a wide shot just in time for us to see the window-shattering blood-splatter of Barry’s latest act of self-preservation; the Coyote runs out onto air.

Before the fall, there’s the moment of gravity defiance. From a fratricide worthy of Shakespeare to a tragedy written by him, the show must go on. And so Barry does, stepping straight from the crime scene to the stage, where his one-line delivery of “My lord, the queen is dead”—animated by the pent up guilt which now overruns his container—arrests the crowd at the class’s Shakespeare showcase, inspiring Sally-as-Macbeth to give the best performance of her career.

“Whatever you did tonight to get to that place, that’s your new process, okay? All you have to do is do that every time.” It’s impossible for Sally to know what she’s endorsing when she gives Barry this encouragement after the show, but her praise is a filter through which he can view his postponed fall as a majestic flight. How fitting that Barry’s stunned mid-air contemplation is played off with John Denver’s “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” the implied crash hovering somewhere yet off-stage.

Road Runner & Coyote Law #9 “The Coyote is always more humiliated than harmed by his failures.”

The odd—and possibly paramount—function of the cartoon world Barry inhabits is to shade the consequences of his violence in palatable, hand-drawn colors. Even though his wake is strewn with viscera (abused partners, orphaned daughters, massacred monasteries), the backdrop of comic surreality allows the carnage to fly by, slipping under the radar of emotional reckoning.

Throughout the seasons, Barry picks up blips of awareness. After murdering his Marine friend in the first season, he’s briefly haunted by visions of the friend’s wife and kid. Much of the third season involves a spurned Fuches visiting the widows and family members of Barry’s many victims and nudging them towards vengeance. Most critically (to Barry’s ego), Gene learns that Barry killed his detective girlfriend and attempts to kill Barry before eventually settling for aiding in his arrest.

But how could Barry be expected to take full accountability for his actions when even their seemingly straight-line consequences take comically unexpected loop-de-loops in making their way to him? When the Marine’s wife later poisons Barry, he’s saved by the father of another of his victims (who then takes his own life, further outsourcing Barry’s penance). When the wife and son of the man Barry murdered in the series premiere seek revenge, the wife ends up accidentally shooting the son instead. When Gene learns the truth about his girlfriend’s death, Barry’s able to temporarily ward off any real blowback by rejuvenating Gene’s career (and threatening his family) as an olive branch.

Whether or not Barry (or the viewer) is feeling it, though, the moral weight of his crimes is slowly accruing. Only someone as delusional as Barry could believe that a few new acting gigs would be enough for even a narcissist like Gene to forgive murder, and by the end of the third season, the unmitigated fury of his late girlfriend’s father, Jim Moss (Robert Wisdom), is enough to convince Gene to sell out his former student.

Naturally, Barry’s much more upset that his beloved mentor could actually be disappointed in him than he is about going to jail, since what should be a devastating blow in a life sentence has no more lasting weight than an Acme anvil flattening Wile E. Coyote, only for him to pop back up undeterred.

Barry’s just as elastic, and prison can only hold him for half a season before he escapes. He wrongly—though understandably, given how often real-life narcissists like Barry learn the same lesson when the system enables them—takes his seeming invincibility as proof of the righteousness of his mission. Rather than trying to understand how the murder of a loved one could possibly turn Gene against him, Barry ludicrously blames Gene for his imprisonment.

A simple desire to kill Gene to protect himself would be plausible for a psychopath like Barry, but the added delusion necessary to feel justified in that desire speaks to how tenuous his remaining connection to reality is (still floating on cliff air). It’s related to the way he’s comfortable letting Sally apologize to him after he screams at her in public; he’s willing to believe anything that allows him to keep levitating, a fact encapsulated in the final season when he cycles through religious podcasts until he can find one where the preacher can justify murder. Barry stops the pod the second he’s had his planned sin pre-sanctified: “Bingo,” he says, stepping out of the car to kill his former mentor for daring to reject the darkness he can only see as his manifest destiny.

*

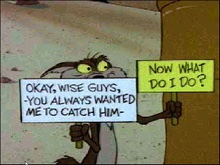

1980’s “Soup or Sonic” short is the only recorded instance of Wile E. Coyote ever catching the Road Runner. Fittingly for such a Sisyphean task, he was only able to do so once a shrinking contraption rendered him an ant to the Road Runner’s giant, and thus tragicomically unable to do anything with the prey he’d so long sought. That led to one of the series’ most memorable and philosophically provocative final shots:

Barry’s final season follows essentially the same plot. Forced to flee LA after escaping from prison, Barry is able to convince his most tragic victim in Sally to come with him. For her part, the downward spiral of her career—due to chain reactions born of Barry’s misdeeds and her own egoist tendencies—and her traumatic self-defense killing of a man who came to kill Barry have sapped her last remaining drops of hope, leaving her with no option but to numbly follow the man who counterintuitively “makes her feel safe.” It’s heartbreaking to watch her do the math on Barry’s verbal abuse and outwardly-directed psychopathy being comparatively tolerable to her ex’s physical abuse, a woman picking from the rogues’ gallery of poisons her life has dispensed.

Barry’s been creepily fantasizing about making a family with Sally from nearly the minute they met, and by this point, he’s so used to the heightened logic of his cartoon world that he’s able to believe in a fantasy as improbable as his. And again, why shouldn’t he? After running like an unchecked train through the overlapping crime and acting worlds of greater Los Angeles, his violence has netted him his dream: after a shocking mid-season time-jump, we catch up with Barry and Sally, now living under assumed identities with their 8-year-old son (!!!) in a middle-of-nowhere mobile home. The desolate backdrop holds a mocking echo of the Coyote’s canyon, only emptier and drained of life and color.

So Barry finally caught his Road Runner, but for what? Wile E. is at least a little reflective, daring to challenge the audience subconsciously cheering for his violence to consider what they actually want. Barry, meanwhile, is still in denial, completely oblivious to the depressed alcoholism of Sally and the sheltered, distorted life his son is forced to live (“Does your mom wear hair on top of her own hair?” he asks a neighbor boy). He’s made such peace with his inner darkness that he doesn’t even notice that it’s infected everything around him. There’s a reason that when Sally trauma-hallucinates a home invader, he’s dressed in a jet-black morph suit—and he looks a lot like Barry.

The only signs of change Barry demonstrates are in the wrong direction, as his denial moves from a passive ignorance to a more active reclamation project. Obsessed with reading about Abraham Lincoln and other great men, he’s thrilled to learn that even the Great Emancipator held some detestable views—a transparent attempt by Barry to recontextualize his own body count as a normal part of the “tricky legacies” shared by so many historical men of note.

This specific brand of autofiction is mirrored elsewhere in the season by NoHo Hank (Anthony Carrigan), the show’s most reliable source of outright humor and thus a natural candidate (in the sadistic eyes of the showrunners) for self-imposed tragedy. The flamboyant Chechnen mob boss—more interested in friend-making than empire-building—historically leads with love. Despite having numerous reasons to wish him dead over the seasons, he really just wants to be Barry’s best friend. And when the Bolivians threaten to take over with their leader, Cristobal (Michael Irby), Hank takes the love-not-war approach and starts a family (and a business) with his enemy.

But even the carefree comic stylings of a man who’d wear this outfit aren’t impervious to the tractor beam of Barry’s darkness. With Barry behind bars and a fresh start at a legitimate operation with Cristobal, Hank can’t still shake his obsession with the killer. So when Barry betrays the friendship Hank thought they shared by ratting to the feds, Hank betrays his own principles by letting the Chehnen elders kill his and Cristobal’s entire staff in return for sparing their lives. It’s the kind of self-serving move his idol Barry would make, so Hank is shocked when Cristobal rejects this new direction and this new Hank.

Rather than face the error of his (and Barry’s) ways, he lets the love of his life get killed by his Chechnen overlords, yet another person’s path to happiness pruned away by their relationship with Barry. In the Barry-est move of all, instead of looking down at the canyon beneath his feet, Hank starts a new business named after Cristobal, rewriting his story as one of unavoidable sacrifice instead of selfish betrayal. Barry would be proud.

Back in the desert, Barry’s not concerned with his own prey’s feelings about captivity—he’s just happy he caught them. Mostly, he’s concerned with convincing them (or himself, please God) that he’s an evolved creature, needing nothing but that empty desert air. That lasts about 20 minutes of airtime, right up until a new Road Runner appears in the form of Gene resurfacing to consult on a Barry biopic. And just like that, Barry goes to dig out his TNT sticks.

Road Runner & Coyote Law #8: “Whenever possible, make gravity the Coyote’s greatest enemy.”

Gravity: as in, the inevitable tug back to LA caused by the black hole Barry left in his wake; as in, the force that finally neutralizes the levitational power of denial.

Barry never does get to use those final TNT sticks on Gene. By the time he gets back to LA, he’s captured on Gene’s doorstep by Jim Moss, who then misconstrues some info Barry gives him, wrongly concluding that Gene was the real criminal mastermind all along. Meanwhile, Sally and her son John follow Barry to LA to stop him from killing Gene, but they’re kidnapped by Hank, who wants to use them to lure Barry so a still-spurned Fuches can kill him.

It’s a mess, basically – an accelerating slide down the gravity well of Barry’s sins. Over four bloody seasons, he’s laid enough dominoes to ensure everyone’s destruction, and they’re finally cascading in a giant, every-car pile-up. These people aren’t blameless—every one of the satellite characters around Barry’s sun is a portrait in miniature of one of his fatal flaws (egoism, narcissism, rage, denial)—but they’re piecemeal. For all their sins, they also have redeemable qualities, and their lives wouldn’t have resulted in this mess if they hadn’t collided with Barry’s combustive evil.

This domino chain culminates with most of our central players gathering at Hank’s headquarters, where they’re each given a chance to do what Barry never has: come clean. First, Sally admits everything to her son. She tells him that Barry is a murderer. She tells him that she is, too. For once in her life, she sheds all ego and just does something selfless, giving her son the freedom of knowing the full size of his parents and getting to make his own decisions about what that means.

Next, in trying to get Hank to own up to having Cristobal killed, Fuches monologues about the very idea of “denial,” admitting that he’s been a poser for all of his life but that getting beat nearly to death in prison finally helped him accept what he really is: “a man with no heart.” It’s a bleak conclusion, but an accurate one – and an acceptance of reality that his protege Barry has yet to achieve. In light of this, Hank still clings to his denial for a moment, until Fuches offers him a clean slate if he can tell the truth. So Hank—finally, heartbreakingly—does.

It’s a beautiful moment, as two victims of Barry’s long arm of violent influence find something like a confessional truce. But this is still Barry, and we’d be as delusional as he is to believe that even two men coming clean could stop the final dominoes from falling after the sequence has already been put in motion. The illusion is shattered, Hank backs out of Fuches’ deal, Fuches shoots Hank, and their men destroy each other in a final act of punctuating violence.

The odd—and possibly paramount—function of the cartoon world Barry inhabits is to shade the consequences of his violence in palatable, hand-drawn colors.Well, not a final act. Sally and John survive the shootout and are mercifully spared by Fuches in a wordless exchange with Barry, who’s just arrived on the scene. While everyone else was inside, truth-telling, Barry was still in denial. Before the shootout went down, he pulled up with a car full of weapons, saying a quick prayer that his violent sacrifice could save his son and wash away his sins, redeeming him. He’s so far gone, even his plans for redemption involve killing.

But that night, when Sally tells him that he needs to turn himself in so that the wrongly accused Gene can go free, he still can’t accept accountability: “I don’t think that’s what God wants for me. I went in there tonight prepared to die… for some reason, He spared me. Honey, I’ve been redeemed.”

“The only way to be redeemed is by taking responsibility for what you did,” Sally replies. Barry chalks that unappealing piece of advice up to Sally being tired and shushes her to sleep. The joke’s on him in the morning, though, when he wakes to find that Sally and John absconded in the night. He rushes to Gene’s house, where he desperately asks Gene’s lawyer if he’s seen his wife and son. The lawyer (Fred Melamed) says that he hasn’t, and begs Barry to take the opportunity to do the right thing and get Gene off the hook.

This is the moment, and Hader’s camera closes in on Hader’s face as we watch him ponder, ponder, ponder the gravity of his situation and the dwindling options in front of him. And maybe it’s the sincere pleas of the lawyer, or the realization that he’s never getting his family back, or the acceptance of Sally’s version of redemption, but the thing that’s been missing in all of Barry’s rampaging pursuits of his Road Runner finally clicks into place.

“You should call the cops,” Barry tells the lawyer. “I’m gonna turn myself in.”

For the first time, the Coyote looks down at the air beneath his feet – and right on cue, gravity kicks in.

The millisecond the words “I’m gonna turn myself in” come out of Barry’s mouth, Gene shoots him through the chest. In fact, Barry doesn’t even get the full sentence out, as Gene’s bullet truncates the “in;” it’s as if the universe was so impatient to administer delayed justice, it was ready to go at the drop of a pin.

Looking up at Gene, the manifested consequences of his actions, Barry can’t believe it. “Oh, wow,” he says, as Gene puts a bullet through Barry’s head. Leave it to Hader and co. to wring one last demented laugh out of the death of our title character.

If only that were the final punchline. After what feels like an interminable cut to black, we’re shuttled once again into the future, where a Sally freed from Barry’s shadow is finally able to modestly succeed as the director of a local theater. John seems to be on good terms with her as well, even though her frozen stare on the drive home from her play tells us nothing and everything about the terrors she’s still haunted by.

Those terrors are illuminated through John, who goes to a friend’s house to secretly watch the inevitable biopic of Barry’s story: a whitewashed retcon that paints Barry as a troubled war hero under the employ of a maniacal Gene. Barry might have paid the ultimate price for his sins, but Hollywood did what Hollywood does, playing the cartoonist and drawing a farce out of his violence.

The final joke’s on us, as the movie’s closing title cards land a double whammy: Gene Cousineau is serving a life sentence for the murders of Janice Moss and Barry Berkman, and Barry Berkman was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery… with full honors. John smiles up at the screen. Even though we just watched him fall, the Coyote has been magically resurrected, immortalized in film so he can haunt the Road Runner forever. Ba-dum-tsss.

True to its namesake, Barry is relentless to its bitter end. But true to its creator, even its darkest moments are cut with both the humor of human folly and the humor of, well, Road Runner cartoons. By using subconsciously familiar Saturday-morning rhythms to disarm us, the show can hit us even harder with the giant ACME anvils it drops on our heads a few times per season. But even when the whiplash is dizzying, sitting dazed with cartoon birds fluttering around our heads can kind of feel like heaven, too.

That’s all, folks!