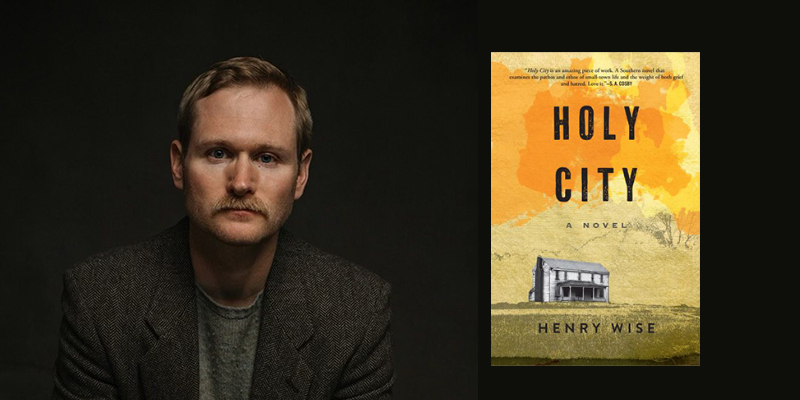

In Holy City, Henry Wise honors the Southern gothic tradition with a captivating and lyrical debut rooted in rural Virginia. At the heart of this gritty thriller, deputy sheriff Will Seems returns home after a decade in Richmond, Virginia, to restore his dilapidated family estate and face his grief and guilt over long-ago tragedies.

After Will pulls the body of an old friend from a burning house, he finds himself at odds with the sheriff who has arrested an innocent man for the murder and seems pleased to move on. The town’s Black community hires a ruthless private detective from the city to help Will find the true killer, but their partnership proves fraught. Complicating Will’s dueling loyalties to his morality and public duty, he remains indebted to a Black friend who saved his life years ago. All the while, Will wrestles with his reluctant connection to the impoverished, swampy landscape he again calls home.

Featuring a diverse cast of complex, soulful characters, Holy City offers both a tightly woven crime plot and a deeply felt treatise on loyalty, justice, courage, and humanity. This dark, lush novel has already garnered impressive blurbs and reviews and I suspect it’ll soon earn more accolades.

Henry Wise is a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute and the University of Mississippi MFA program. His poetry has been widely published. I connected with the author over Zoom to discuss his debut. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Jenny Bartoy: The theme of home pervades this story. Will returns home where a variety of ghosts and guilts await him. For several of the characters, home is fraught — whether that home is a house, a family, a culture, a county. Can you tell me more about how you played with this theme?

Henry Wise: Will’s got a foot in two different worlds, so he doesn’t really belong entirely anywhere. He’s held suspect in what he considers his home. He returns to it and it’s not what he expected entirely. And he’s got a foot in Richmond, he’s been there for 10 years, but he doesn’t really belong in Richmond either. This idea of inner division between urban and rural Virginia, and how he doesn’t really belong in either place — that sort of ended up controlling a lot of the narrative. You know, Thomas Wolfe said, “You can’t go home again,” but what happens when you do? What happens when you try to get back in touch? Drug use is a theme in the story, and Will is not a drug addict, but returning home in a way is almost like a relapse. He probably shouldn’t go back if he knows what’s good for him. But he does. There’s this thing that’s pulling him. We think of “Home is where the heart is,” and “There’s no place like home.” But what if home is also toxic?

JB: This novel feels very intimate, in that you dive deep into each point of view (POV) that is shared, but the story rotates through an impressive number of POVs. This felt to me like old-school narration, almost omniscient, but with a modern emotional depth. How did you navigate this balance?

HW: I think POV is one of the hardest things for writers. If you’re writing a memoir, it’s probably going to be in first person, it’s a little easier to make that decision. But in fiction, you can do almost anything, that’s wide open. There was a time that I thought about writing in first person from Will’s POV and the limitations there. I think what is achieved by the third person, and being able to freely follow different characters, is far greater than what it would be just following Will. I ended up realizing these characters are fascinating, and I think there’s something in the world that connects them. Will’s our lead but he’s not the only interesting character.

I didn’t set out to say, okay, I’m going to write about each one of these characters, but it’s so organic to the process for me. I ended up writing from other perspectives. I had to find something in each character, whatever made them human, even the most despicable or the most troubled. Is there a glimmer of hope in this person? Is there something I’m rooting for in this person? Writing about the complexities of each individual was also the fun part for me. Each one of them emerged from the two-dimensional to really form three-dimensionally, and I felt that I had been dropped in this fictional county, and that I was meeting everybody there.

I’ve realized in my rereading of Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim recently, how deeply he gets into the psychology of these characters and explores cowardice and heroism and the thin line between. Authors like him and William Faulkner and Willa Cather, they really get into their characters. And so maybe there was a more contemporary psychology [in Holy City] but definitely influenced by some older authors.

JB: Holy City isn’t a traditional whodunit in that we discover who the culprit is fairly early on. The mystery becomes instead whether they will be caught, and then whether the characters will get justice. Tell me about this narrative choice.

HW: Yeah, I think the crime almost takes a backseat. You think it’s going to be a whodunit, but then you’ve still got something like 100 pages before the novel ends. There is that mystery that drives the book at first, it gives us a reason to follow Will on a bit of a shallow level, a little closer to the surface. But we learn fairly early on as well that Will is driven by his past. And that’s really what the story is about, not just about Will, although he is the one coming back to face his past, but it’s really about this return home. The crime and his past collide, and he has to deal with both. And in fact, the crime functions to bring his past to a head. Some might fault some of his past behavior as cowardly, but at the same time he’s returned to face these traumas and tragedies of the past, and I think there’s a real courage in that.

JB: This is one of the darkest, grittiest novels I’ve read in some time. You cover a variety of tough topics: murder, suicide, addiction, necrophilia, incest, poverty, racism, family estrangement, to name a few. How do you keep your own head above water when exploring such darkness?

HW: It is a very dark book, but these characters are trying in their own way to deal with their lives. And I wouldn’t say that this book is uplifting, but I think there can be inspiration in the courage of a particular moment. People deal with messy lives all the time. And people deal with grief. I’ve been touched by it, everybody has, and I think it’s worth exploring.

I met Richard Ford a few years ago and I asked him, “What advice would you give somebody who’s writing a first book?” and at first he said “Don’t do it” like a joke, but then he gave me some of the best, most meaningful advice I’ve ever received as a writer: “Write about what’s most important to you, because that will sustain you.” And I think, if we’re going to write a book, let’s get in there and write it and get dirty. I didn’t want to just throw all these dark things in there — some books do that and it feels almost gimmicky — but the characters emerged organically and they surprised me. I had pictured [some of them] as 100% villain or 100% corrupt, and then this person shows a glimmer of love or wants to protect somebody. That to me as a reader is an enriching experience.

JB: You write with such compassion for each of your characters. For me, that really balanced out the darkness. There was such heart to the story. You just touched on this a little bit, but I’m curious: what’s your approach to character development?

HW: It’s a long process. [I spend] a lot of hours exploring each character and trying to see them almost as a movie. I write a lot of scenes. Everyone’s got a different approach — I write for surprise. There are a lot of pages that are written and never make it in.

Kurt Vonnegut said in his eight rules for creative writing to “be a sadist” towards your characters. To some extent, you need to find out what they’re made of. And to do that, you have to challenge them. That pressure is so important, especially for Will. He’s the deputy sheriff, and he doesn’t agree with what the sheriff and many others think about the crime at hand. He’s also doing some things illegally. He’s also facing his past. All of these things kind of put him in a vise and something’s got to give. And I feel like the setting itself also does that. The [small Southern town] setting helped me explore these characters, because they’re either stuck there and trying to get out, or they’re just stuck there and falling into the ruts of life in an economically challenged area.

JB: This novel is a delight for the literary reader. One blurb said you “bring a poet’s ear to the Southern landscape” and that encapsulates your writing style perfectly. What is appealing about the South for you as a writer?

HW: As a Southerner, I wasn’t just born in Virginia, but I was raised as many Southerners are with a real sense of “This is where you’re from” and “This is home.” I think for me, there’s always been a division within, as a Southerner, partly because I grew up outside of Richmond, Virginia, but I’ve got family and deep roots in rural Virginia. My grandmother grew up in the house that my cousins now own, that goes back to 1834. It’s got the original French wallpaper and nothing has been renovated in the old part of the house. You step into these places or into a family graveyard, and you can feel the centuries and what’s beneath them as well, the fact that Native Americans were there before. Buffalo used to roam even in Virginia.

I’ve been aware of all of these layers of history for a very long time. I think I was tired of the Civil War the day I was born! The South to me can be convoluted. It’s also a beautiful place, with beautiful people. And I think the writing almost has to be a bit convoluted as well and poetic. It’s almost a snake bending over itself — you think it’s one thing but it becomes something else. And the writing became a lens through which to see this world. I think Holy City is a book where the writing itself is a necessary component. It’s not just the story. It’s not just the plot, the writing itself also colors how you see this world. And I think it makes sense in the South, but I might write a very different book set in Wyoming or something.

JB: You have a great line in the novel, about how “Justice had no meaning, only consequence.” At first, this seems to imply revenge, but by the end justice seems to be more about redemption or maybe karmic balance. What’s your view on justice after writing this novel?

HW: There are different kinds of justice, and this book grapples with a few of them. One is of course, legal justice, which seems not necessarily the purest form of justice. And I think Will is after something pure. He doesn’t know what that is, he’s really searching for it. And it seems that the more he tries to achieve it, the more he drives people away or hurts them. Justice goes far deeper than legal justice. I think you’re right in redemption. How can you live with yourself if you’ve done something unspeakable? But we’re also talking about historic justice. There’s a sense of being oppressed by one’s own legacy and history, which is also tangled up in that landscape.

I think eventually Will realizes that he’s got to do something to get out of his head. And finally he does, and I don’t know if it’s the right decision, but it’s his decision. [The writer] Chris Offutt one time said to me: “The perfect ending is both surprising and inevitable.” I hesitate to say that something is always true, but for me, that is a really good thing to strive for. To his credit Will seems to maybe achieve some sort of redemption by the end.

JB: What’s next for you?

HW: I’m working on another book set in the same area. So this will be a series of sorts, but I want every book to be a new story. Some characters may come back. Certain threads may come back. This one is going to take place primarily in the Snakefoot region, which appears in Holy City. I’m really fascinated by that and how it harbors misfits, outcasts, secrets, and the potential of the supernatural even. It’s fictional, but there were places, particularly the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia, where entire communities of Native Americans and escaped slaves would retreat and actually live there. And I was thinking, what if we see the continuation of that? And that’s the power of fiction to me. It’s fun to write about places that may not exist, but absolutely could have.