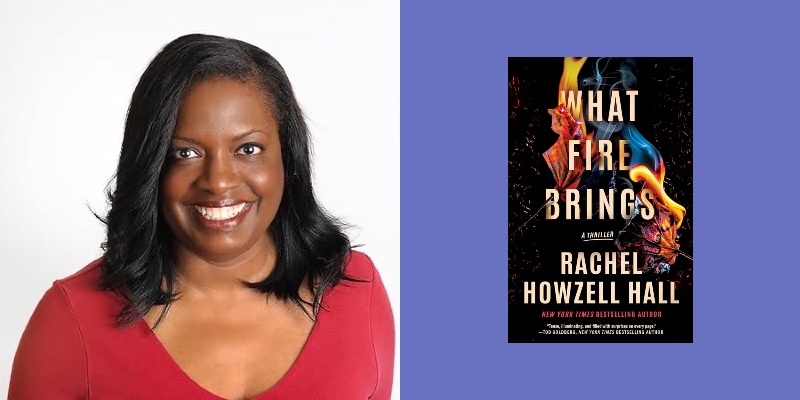

Rachel Howzell Hall had what can only be described as an annus horribilis while writing What Fire Brings, which was published on June 11, 2024. Her father, both her in-laws, and her dog all passed away during that year. But, like the protagonists who persevere in her novels, Rachel prevailed. That’s not to say there wasn’t a toll: for the first time ever, in a writing career on top of a full-time job during which she often wrote in the car before going into her office, a battle with breast cancer, and all the varied vicissitudes of life, Rachel couldn’t make the book’s deadline. Knowing Rachel, that’s not a big deal, it’s a huge deal.

Rachel’s herculean challenges are mirrored by Bailey Meadows, the protagonist of What Fire Brings. Bailey arrives for her undercover assignment posing as an aspiring crime fiction writer at the Topanga Canyon compound of one of the genre’s most successful scribes, battered, bruised and with a knife wound to her side that she’s not sure how she got. Wounds notwithstanding, Bailey is determined to find Sam, a woman who went missing in Topanga Canyon more than a decade before, for an organization called The Way Home. Neither Hell nor high water will stop her. Well, maybe Hell—in the form of a canyon wildfire—just might.

Nancie Clare:

Writing this book was a challenge, to say the least. Your father, in-laws and dog passed away during the year What Fire Brings was written.

Rachel Howzell Hall:

I mean, we write about death [in our books] all the time, but to actually be involved in it, while trying to manage your work life? So yeah, [that year] was extra crispy. It’s been extra, extra crispy.

Because of the multiple layers of What Fire Brings—it’s the twistiest story I’ve ever written—I couldn’t get it together. My brain wouldn’t. I was totally exhausted. I’ve never missed a deadline in my entire writing career. My life was one big, big strand of fish line that refused to untangle. I tend to repress [my feelings]. I have to keep going because people rely on me.

And it just gets worse and worse, and then you’re stuck, which is why we use writing in the first place: to get unstuck. I had been so invincible, but no matter how smart and talented and invincible you think you are, there’s always that thing that’s going to stop you. And you’ve done nothing to deserve it. It just is. And for What Fire Brings, it was kind of like a perfect in-class tutorial of what? Grief and being unable to solve it, to think through it, to see the fires and know that they’re fires. Until the last minute and then you pull it out with the grace of God and the grace of family and friends! That’s how it felt. I put a lot of myself in my stories, and I want to earn my twists organically. And I think that me having so many deaths back-to-back, if I didn’t experience it, I would’ve said, “That’s impossible. How could something like that, death after death after death, happen? Really?” But yeah, it did. What do you do with that? That’s going into this book. This is how it is to be lost and in the dark and needing to get going.

Nancie Clare:

Bailey Meadows is complicated. She’s posing as an aspiring writer, arriving at a literary event at the Topanga Canyon home of Jack Beckham, a famous bestselling crime fiction writer. And she’s the only Black woman there. Only she’s not an aspiring writer about to take up a writing residency. She’s an undercover P.I., there on behalf an organization committed to searching for the missing, looking for a woman named Sam who had disappeared in this same part of Topanga Canyon. And, unlike earlier in her investigation, instead of talking to sketchy people in sketchy places, Bailey is going to embed herself in the world of Topanga Canyon. Where did that come from?

Rachel Howzell Hall:

My first real job out of college was with the PEN Center USA West. And the bulk of the writers and boards of directors were wonderful, wonderful white folks of Los Angeles. They lived in Beverly Hills, they lived in Topanga Canyon. And as the administrative assistant, it was my job to go to the parties with the envelopes of tickets and take notes or show people where the bathroom was. So that comes out of my real-life experience of going to these spaces where I’m typically the only Black person there.

And a famous LA novelist who’s now passed, Carolyn See, [lived] in Topanga, and I loved her. She was one of the most wonderful writers I’ve ever met. And I just remember hearing her talk about Topanga, and I’m like, “What is it? Topanga Canyon?” I’m a native, but I live in South Los Angeles. I don’t know nothing about Topanga Canyon! [Laughs] It was always that place in the woods somewhere that I could kind of see as I passed by on [Pacific Coast Highway]. Growing up in the church, especially as a Seventh Day Adventist, Topanga Canyon felt like this kind of forbidden place for Black Christians down in South Los Angeles.

I wanted that for Bailey: to be in a place where she’s an “other,” in an “other” place. That’s me, my career going to book events in these places where you’re the only Black person. It’s like, “I’m smart, but what is happening right now?” It was just a weird kind of thing for me. And then, Topanga is a place that’s always on fire, now more than ever. The hills are alive with fire all the time.

Nancie Clare:

For someone who is obviously fond of your protagonists, you do beat them up. Mercilessly!

Rachel Howzell Hall:

I do. You know why? I feel beat up sometimes. I think: is God just putting me through my paces because He knows that I need material? I don’t know. But I think things that don’t bother other people bother writers. And because of that, we make things a little harder for ourselves. I reflect that in my characters. They’re professional women, they’re lovely people, but bad things happen to lovely people all the time. And I want to figure out how someone who seems to have it all fights to keep it. I get bored with characters who don’t have to fight for anything.

I feel like I’ve fought for every success that I’ve had. I’ve fought for it being a Black woman in this field, a woman, period. I fight for space in everything. I guess that’s just my nature. And I want people to look at my characters and say, if not a hundred percent, I’ve experienced fifty percent of what this character’s going through, and this is how she’s solving it, huh? Let me think. Can I figure something out that will help me in that? It’s part me seeing myself, part public service announcement, part making interesting stories about interesting people. People are incredibly interesting, even the most boring ones. I think [boring people] are hiding something!

Nancie Clare:

One of the things about your characters in general, and Bailey in particular is that she is continually underestimated: because she’s Black, because she’s not wealthy, or connected. She’s not a nepo baby. People assume she’s there because it’s Affirmative Action or DEI. Someone actually says to Bailey at the party, “you’re only here because you’re Black.”

Your characters fight that sort of preconception and underestimation, and to me it seems that your stories travel on two tracks: Your protagonists are investigating, looking for truth; and the fight they have with the people surrounding them. It’s as if they have to say, “yes, I am a legitimate person regardless of my sex, regardless of my color, regardless of my economic background, this is who I am.” I can feel Bailey’s frustration.

Rachel Howzell Hall:

Women especially can read this and say: I know what it is to be in a room like that where people are like, “oh, you’re only here because of whatever.” You feel it going into a space, you feel it even outright when someone reviews your book on some website and says, “I haven’t read it, but it’s probably woke, so one star.” Or “I haven’t read it, but it’s affirmative action, one star.” You can’t reach those people, but the people who leave two stars, three stars, those are the people who are like, “oh, we vote [the right] way,” but they still see you as an interloper. It’s frustrating. For Bailey, she can’t even look for a missing woman without having to deal with her legitimacy.

Nancie Clare:

Sam, the person that Bailey is looking for, is suspected of having Dissociative Fugue Syndrome. To quote from What Fire Brings, it’s “a condition that causes people under great stress or experiencing trauma to lose their identity and impulsively wander away from home.” How did Dissociative Fugue Syndrome come to your attention and what caused you to use it in the story?

Rachel Howzell Hall:

It’s a real thing. I read about it a long, long, long time ago. It’s always kind of been [in the back of my mind]. And then I saw Memento, and it’s like, “Ooh, what? I like that story.” And then I read Shutter Island, and it’s like, “okay, but how do I do something like that?” Then about two or three years ago, I read a story in the New York Times about a young teacher who wandered off after a hurricane down in the islands. She showed up somehow in the New York Harbor and had no idea how she got there or where she’d been. And then it happened again, and no one knows where she is. Then when I read that PTSD tends to bring it on, and everything that my family had been going through, it’s like sometimes you wish you could just [say] “I don’t even know what all this is or who you all are. I’m going to just create this new existence just so I can have a breath.”

There has been this back and forth over whether fugues are real or not, because you can’t see it on a CT scan. I mean, what keeps us all from just pretending to space out and wander away and not return to something that’s hard. I mean, I find it fascinating that it can’t be seen, and yet it happens.

Nancie Clare:

Let’s talk about Jack Beckham, the best-selling crime fiction writer. He’s a handsome white guy with a tragic story and a creepy vibe. Fortunately, in real life there are very, very few unsavory characters in the crime fiction community—but there are some. Was Jack Beckham inspired by one of these guys? Was he taking advantage of Bailey because having a writing partner who is a Black woman is going to appeal to a demographic that his books might not have?

Rachel Howzell Hall:

He was inspired by some of our peers as well as writers [who came] before us. Jack Beckham is [the guy who says] “I want to teach you how to do this thing, and so come to my house and I’ll show you.” Maybe I don’t know what their intentions are, but it always comes out that they are assholes; they’re not doing it for you. They do it because they will look better politically and sociologically. Beckham wants to use Bailey, to appropriate her Blackness for his own.

I was trying to come up with a character who, on his face, looks benevolent and generous because he opens up his home and he has this tragic backstory about his wife, and [the reaction he expects is] “oh my gosh, you’re so wonderful. Thank you for giving me this opportunity.” And it’s all bullshit. It’s all fiction, it’s all lies. And again, as fire comes, fire cleanses, and I wanted his whole estate to be burnt down, and never have it rise again. But eventually, if there is another story, a sequel to this book, there’d be someone like him to take his place, because that would be interesting.

Nancie Clare:

You’ve been nominated for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize a time or two, the Lefty, Barry, and Anthony Award…

Rachel Howzell Hall:

Yes, I have. Yeah. Yeah. I just like trophies, period. My dad was a trophy hound, and so I grew up in a house of trophies, and so that kind of burns me. It’s like, ah, I have to win one! But at the same time, my readers, people who enjoy my books, they really do enjoy them. And I like that. I like being able to do interesting things with each book. I don’t ever want to write the same book. As a writer, you’re also learning new ways of telling a story because you read a lot. I remember reading Dennis Lehane and saying, “oh, man, I want to write a story like that!” And it takes me years to figure out how to do it.

When I finally do it, it’s like, did I land? Did I do it right? Am I honoring my heroes? When I’m feeling like, “oh, man, why can’t I win something? Why do I constantly compare myself?” I’ll just go over to GoodReads and read reviews on Shutter Island, which I think for me is one of my pinnacles. I see how some people just didn’t get it. It’s like, okay, well, if they don’t get him, then I’m good. Because I think he’s one of the most talented writers in the existence of crime fiction ever. So that’s how I soothe myself, by looking at the Dennis Lehane reviews!