There are few places in the world that inspire awe and terror like the Alps. With peaks that top 4000 meters and immense crevasses cracking through granite, the Alps give a god-like vantage above the world one minute only to plunge one to its depths the next. This dizzying sensation was best expressed by the French essayist Chateaubriand when he wrote: High mountains suffocate me, and while the lack of oxygen is certainly a factor, it is just one of the elements that make the Alps the perfect setting for chilling crime, suspense, and horror fiction.

One of my favorite novels set in the Alps is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, published in 1818. Shelley perfectly captured the tone of the Alps as a majestic, claustrophobic place of melancholy and the sublime. While much of the story is set in Geneva, Switzerland—not exactly the most frightening place in the world—my favorite scene in the novel occurs when Victor Frankenstein travels to the Alps in search of his runaway creation:

The high and snowy mountains were its immediate boundaries, but I saw no more ruined castles and fertile fields. Immense glaciers approached the road; I heard the rumbling thunder of the falling avalanche and marked the smoke of its passage. Mont Blanc, the supreme and magnificent Mont Blanc, raised itself from the surrounding aiguilles, and its tremendous dome overlooked the valley. (p107 Frankenstein )

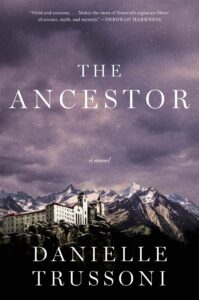

Frankenstein’s Mont Blanc was on my mind when I wrote the novel The Ancestor (2020), in which an American woman, Alberta, takes an ancestry test and discovers that she is related to the Montebiancos, an Alpine clan. As it turns out, Alberta is the last living member of the family, and has inherited a fortune, including a crumbling castle in the Aosta Valley, one of the most remote corners of the Italian Alps. When she goes to investigate, she becomes trapped by snow for the winter. Over the course of her months at the castle, she discovers the truth about her family, and a terrifying secret that the family has struggled to keep hidden.

While writing The Ancestor, I went to the Aosta Valley and found the landscape to be as dramatic as I had always imagined it. But what stayed with me—and came to be part of my novel—was the human presence that has persisted in this unwelcoming landscape: the hearty stone houses of ancient hilltop villages; the medieval castles that have survived the elements for centuries; the dialect of Franco-Provençal, still spoken some parts of the Aosta Valley; the fairy tales and legends; and the mountain guides and adventurers who have trekked into the mountains only to dissolve in the fog.

Like The Ancestor, Antonio Manzini’s Black Run (2013) is set in the Aosta Valley. A mutilated body is found on a piste above Champoluc, and a deputy prefect of police finds himself entangled in the mystery. Manzini explores the nuances of life in a small Alpine town, giving the reader the experience of seeing and hearing Italian, learning about the customs, and coming to understand the unique history of the region. Manzini is an Italian actor, director, and screenwriter—the novel was written in Italian and translated by Antony Shugaar—and his sensitivity to the nuances of Italian culture gives the novel a layered and intimate perspective, as if you’ve been invited into the home of a native. The landscape is gorgeous, the mystery propulsive, and after reading Black Run, you feel that you’ve taken a frightening holiday in far-away country.

Such is also the case in The Sanatorium by Sarah Pearse, published in March of this year: a detective takes time off from work to meet her brother and his new fiancé at a Gothic sanatorium in the French alps. The sanatorium has been rehabbed into a luxury hotel, but still retains much of its former character, which aptly reflects the gloom and dread of the mountains. While the trip is meant to be personal, when the fiancé goes missing, the vacation morphs into an investigation. The Sanatorium has everything that I love about mysteries set in the Alps: it’s an eerie drama that plays out against a landscape that inspires vertigo and claustrophobia.

Disappearing in the Alps is a theme crime writers have used time and time again, and two stories in Agatha Christie’s classic The Labours of Hercules (1940) have Poirot searching for missing persons in the mountains. In The Arcadian Deer, Poirot goes to Switzerland in search of a mechanic’s missing lover, and The Erymanthian Boar, which follows Poirot up a funicular to a mountain-top hotel where he finds himself tracking down a Parisian gangster. These stories aren’t frightening, and are characterized by Christie’s neat and satisfying style, but they underscore a perennial theme of the Alps: wander too far from fortification, and you might be lost forever.

At the very least, the Alps insure a lost internet connection. Contemporary mysteries set in the Alps have the added pressure of our 21st century fear of disconnection. This new dimension of anxiety ratchets up the tension of any situation, but the threat of being lost in a wilderness of ice and snow without cell service or Wi-Fi is, well, a nightmare for many of us. At present, there are few places on earth without Wi-Fi, but high in the Alps is one of them (deep below the ocean would be another), and this threat provides a shot of adrenaline to a story that might have been easily solved with a phone call or text message.

Being cut off from civilization is also central to Ruth Ware’s One by One (2020). Snoop, a London tech-start up, organizes a company retreat in a chalet in the French Alps to promote mindfulness. The retreat becomes a lockdown when an avalanche hits. As members of the group begin to die, Zen goes out the window. One can’t help but cheer as some of these people are confronted with the realities of nature, which cares little about tech-startups, success, or mindfulness. Perhaps because of the nature of the characters, there is little in the way of reflection to be found, and Ware doesn’t take advantage of the poetry or grandeur of the landscape. Nevertheless, One by One does what every good novel set in the Alps should: allows one to get lost in its mystery.

***