Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,

there is a field. I’ll meet you there.

–Rumi (1207-73)

Several months ago, everyone I knew seemed to be watching Bridgerton, and a friend described it fondly as “a bonnet drama—one of those historical shows that are pure escape.”

This was around the time I was revising Under a Veiled Moon, the second historical mystery in the Inspector Corravan series, and I found myself mulling over the notion that an “historical show” was a “pure escape.” What did that mean? Was it a “pure escape” because we are emotionally removed? After all, none of us has a dog in the fight in Regency England. Or perhaps it was because the main romance has a satisfyingly happy ending. However, even in the well-mannered world of Bridgerton, issues surrounding class, race, occupation, and gender arise; the world of slavery and overseas plantations intrudes; and we certainly observe the harmful effects of social media vis-á-vis Lady Whistledown’s broadsheet.

I love beguiling characters and beautiful costumes as much as anyone, but I don’t consider most historical fiction to offer a pure escape – and historical mysteries, with their life-and-death situations and the fear and responses they entail, often provide even less. Indeed, while I never intend to write a novel with a “Message,” I find (often belatedly) that by diving deep into the unevenness and injustices in Victorian culture, I have inadvertently placed a fraught issue from my own world at the core of a mystery. Five books in, I have come to see that when the world inside the novel (e.g., 1870s London) and the world of the reader are far enough apart, the distance between them becomes a creative space, like Rumi’s “field” free of “ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing.” On this fresh ground, both authors and readers can set aside present-day ideas and the associated (often charged) feelings and examine a societal challenge, a response, and the psychological tendencies that underpin that response from a fresh perspective, to imagine some alternatives that are potentially kinder, more grounded in empathy, and less divisive.

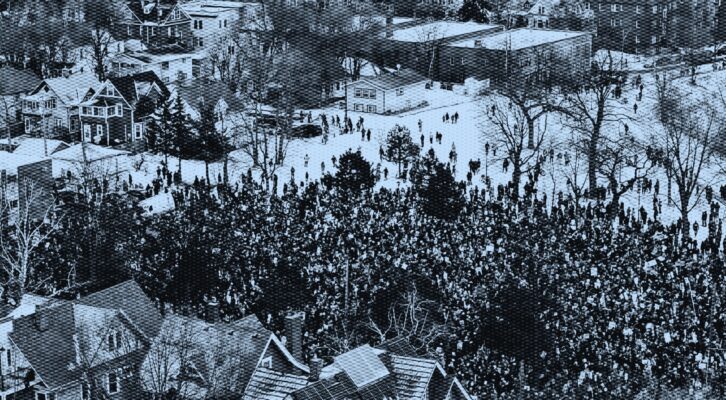

For Under a Veiled Moon, I brought together three historical elements that twine together around the challenge of racism, a response of fear, and a tendency toward simplification. The inciting event is a maritime disaster: on September 3, 1878, a 900-ton iron-hulled coal ship collided with the small pleasure steamship, the Princess Alice, and sank it, throwing all 630 passengers into the Thames River, where over 500 drowned. It is still considered the worst maritime disaster in London and threw the city into a panic – partly because with no passenger manifest, there was no way of knowing who had been on board. Naturally, there was an investigation into the cause, with the assumed goal of assigning blame to one ship, or one person on a ship.

As many psychologists explain, fear causes us to crave certainty, to want a simple narrative, to seek to locate blame in one place, so as to reduce the complexity of the problem that needs solving. However, the simple narrative is often a misrepresentation. A reduction to a single cause tends to sideline the very nuances that we should attend to. So this Princess Alice disaster enabled me to explore the dangers of fear and the resultant tendency toward simplification, even while having compassion toward those who gave into it.

True history tells us that both ships broke nautical laws. But in my book, the early clues point to the Irish Republican Brotherhood because I wanted to explore a second historical element: racism. I stumbled upon Victorian anti-Irish discourse during my research for Down a Dark River, the first Corravan mystery. One notorious example that separates the Irish “race” from English “character” comes from Benjamin Disraeli, who became Prime Minister and a favorite of Queen Victoria. In the London Times, he wrote a pseudonymous letter that is polarizing, inflammatory, and full of misrepresentations: “The Irish hate our order, our civilization, our enterprising industry, our pure religion. This wild, reckless, indolent, uncertain, and superstitious race have no sympathy with the English character. Their ideal of human felicity is an alternation of clannish broils and coarse idolatry. Their history describes an unbroken circle of bigotry and blood.”

My protagonist, Inspector Michael Corravan, immigrated as a child from County Armagh and grew up in the Irish section of Whitechapel with the Doyle family. He still has Irish physical markers and an accent, and he often faces anti-Irish (as well as anti-police) prejudice. The reader observes racial injustice as an element of Corravan’s lived experience, and our emotional empathy (rather than our intellectual “ideas”) enables us to consider the devastating effects of racism upon both a group and an individual.

The third historical element is the social media of the Victorian era: the 1,000 newspapers circulating in London. As they do today, the newspapers produce narratives that shape public perception. In my book, a malevolent group organizes the publication of fearmongering hints and rumors about the Irish Republican Brotherhood across several newspapers. Taken together, the newspapers reinforce each other’s false narratives, and the repetition has the effect of making the rumors seem like a single, straightforward truth. This version of events has material effects in Corravan’s world and leads directly to more deaths. By showing the effect of the engineered duplicative accounts in newspapers, I suggest that we cannot take even accidental repetition as producing truth.

The drive to find a single, simple account, and a single group to blame, is a strong one because fear stokes our need for certainty and simplicity. But in recognizing fear for what it is, we can separate out the feeling from our response. We can recognize that our tendencies to create simple narratives and to cast blame upon a single individual or group may be instinctive, but they are not inevitable. We have choices.

We’ve all heard the adage that we look at history, so we don’t reenact it – because (as Freud explained) we unconsciously repeat what we do not consciously remember. Perhaps historical mysteries (and historical novels generally) offer not only an escape from our world but also an escape from our initial, instinctive fears and responses, so we might find the empathy that can lead to genuine understanding and connection to people in our present.

***