Every writer I know has a finely honed system for avoiding writing. Some develop a sudden need to deep-clean their houses when they’re on deadline. Others (fantasy writers, in particular) convince themselves that they can’t write the story until they’ve fully developed the monetary system and international trade patterns of the world they’ve imagined.

For most writers of historical fiction? It’s research.

I’m guilty. Oh, am I guilty. For anyone working in the Gilded Age, research is a marvelously effective means of procrastination. There’s just so much fascinating historical minutia available from the period. Photographs, letters, dinner menus, personal diaries, and even telephone directories are all there for the perusing. I sit down to write, then convince myself that I desperately need to locate and study an antique transit map or check the newspaper headlines for a particular week. Before I know it, hours have gone by and I haven’t written a word.

But even though it lowers my wordcount, I can’t say I regret the time I’ve spent immersed in the history of Gilded Age New York City. After all, I wouldn’t write in the period if I didn’t love it. And it may make me a slower writer, but I also believe it’s made me a better one. I’m proud of the level of historically accurate detail I include in my novels (hopefully without detracting from the story). And the research I do frequently gives me new plot ideas.

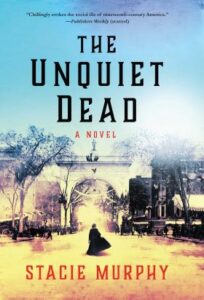

In fact, it was while researching my first novel, A Deadly Fortune (Pegasus Crime), that I conceived of the idea for its sequel, The Unquiet Dead.

My main character, Amelia Matthew, is a young psychic who works in a risqué nightclub near Washington Square Park along with her foster brother, Jonas Vincent. Although most of Amelia’s first adventure takes place in the notorious city insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island (modern-day Roosevelt Island), and I did do plenty of research on that institution, I spent an enjoyable afternoon avoiding writing about it by reading up on the history of Greenwich Village instead.

In the decades before the Civil War, the streets just north of Washington Square Park were popular with wealthy New Yorkers, who built the stately townhomes still visible there today. Their Black servants settled south of the park in an area that soon became known as Little Africa. After the Civil War, the wealthy New Yorkers moved further north, but Little Africa—concentrated in the blocks around Minetta Street—remained one of the hubs of New York’s Black community.

In the decades around the turn of the century, the racial mix of the neighborhood changed, thanks to an influx of Irish and Italian immigrants drawn to the area by cheap rents. It was one of the most integrated areas of the city at the time. It was also one of the poorest. Crowded tenements and cheap boarding houses predominated. Many of the Gilded Age’s infamous “black and tan” saloons—where Black and white patrons drank and gambled and debauched themselves side by side—were located within a few blocks of each other. Crime was rampant. It was said that the area was so dangerous that even police officers would refuse to walk down Minetta Street after dark.

Mixed in with the criminal element were hard-working, upstanding families just trying to get by. One of these, according to census records, was headed by Morgan J. Austin, a Black man who lived on Minetta Street with his Irish wife, Annie, and their children—including a 15-year-old son who worked in a laundry. Morgan and Annie Austin fascinated me. What was it like for them to be an interracial couple in New York City in the 1890s? How did they meet? How did their families react to their union? Such personal details aren’t recorded. But when I discovered that Morgan had been employed, as many Black men were at the time, as a waiter, the potential connection to Amelia and Jonas’s world was obvious. I knew I wanted to incorporate them into my next book in some way and to try to write a little bit about what their life together might have been like.

In The Unquiet Dead, Morgan Austin became Miles Alston, a waiter at the same club where Amelia and Jonas work. His 15-year-old son, Amos, who works at an industrial laundry, is accused of a heinous crime—the kidnapping and murder of a child. Miles and his wife, Polly, turn to Amelia and Jonas for help exonerating him. Their efforts to defend him, and their growing suspicion of his guilt, form the backbone of the story.

There are so many things about the Gilded Age in the United States that feel as though they parallel the United States of today: extreme wealth disparities, hostility to and scapegoating of immigrants, and very energized social reform movements.

I first had the idea for The Unquiet Dead in 2018, before the murder of George Floyd and the renewed strength of the Black Lives Matter movement. Writing it in 2021, it felt more keenly relevant, and I felt an even greater obligation, as a white writer, to portray Amos’s experience—as well as that of his family—in a thoughtful, nuanced way. Amos is a Black teenager. His alleged victim is a little white girl from a wealthy family, and her disappearance has been heavily reported by the newspapers. Everything is stacked against him. And even the people working on his behalf have biases they’ll have to contend with if they’re going to be successful.

In A Deadly Fortune, I tried to highlight the way class and gender dynamics colored peoples’ lives. In writing The Unquiet Dead, I wanted to shine that same light on the racial structures of the time and hopefully encourage readers to think about the ways things have—or haven’t—changed.

***