Houdini, maybe the most famous escape artist of all time, astonished audiences with his ability to shed shackles and chains (at times even bound by a straightjacket) while submerged in a tank of water without a breathing apparatus, the clock ticking, his very life on the line. It takes my breath away just thinking of it.

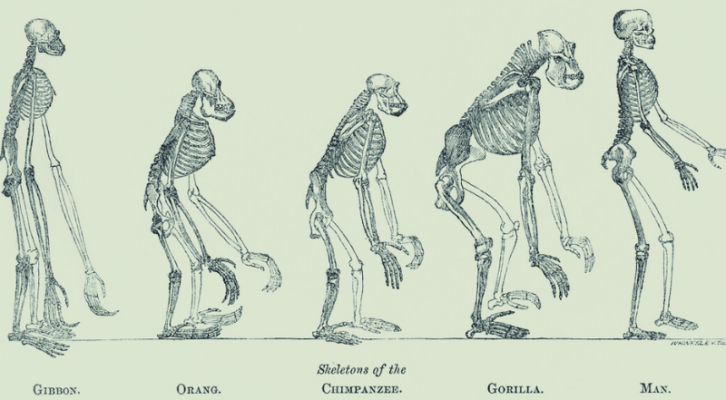

Most artists are “Houdinies” of a sort, illusionists able to free themselves from the shackles of convention, break through the rational boundaries of science, slip the straitjacket of logic, the clock ticking! Their artistic lives on the line! (Okay, maybe the “clock ticking” and the “lives on the line” is a bridge too far.)

Nevertheless, many writers can end up chained and shackled by another restraint: artistic bias. Detective novels, science fiction, horror, fantasy, romance, and just about anything else that isn’t considered “literary” is usually relegated to the category of Escapist Fiction, (Oh, my, what is that?) a term not always used favorably. Escapist Fiction helps us escape the mundane and terrifying aspects of our real world. But doesn’t all fiction, literary and otherwise, transport us temporarily from our everyday life? I mean, isn’t that kind of the point? Then why the distinction?

Let me introduce you to my little friend, The Role of Art. And what is the role of Art? Well, from what I can gather, nothing less than saving the world. Revealing universal truths, plumbing the depths of human suffering, teaching us about ourselves and our proclivities, imbuing our pointless lives with meaning. Is anyone or anything actually capable of such a Herculean task? Much art may actually realize some success in reaching these lofty goals, though art with the intent to “teach and save” from the outset usually falls prey to pretension and contrivance.

I doubt consumers of mystery, romance, thrillers, science fiction novels give one fig how literary criticism brands the fiction they love. (BUT THEY SHOULD!! Scream the literary intelligentsia. Just kidding, guys.) However, the battle rages on between accessible fiction and erudite prose, the later believed to be some nefarious conspiracy to condescend and exclude, while the former is purely some commercial ruse to make a buck. And what’s at stake in this battle between escapism and true art? Well… our very existence hangs in the balance, the future of humankind! Not really, but at times it feels that way. (Can’t we all just get along?)

But are we missing the point? Does The Stand by Stephen King engage its readers any less than The Shipping News by Annie Proulx compels its own audience? And don’t they each have their own individual audience, as well as a shared audience? I for one have immense admiration for both of these authors. And don’t these works of fiction both harness their power through the imaginative manipulation of narrative and the masterful use of language? I do find it ironic that the “art world” with its insurgents so quick to point out the injustices of a flawed society, are also very willing to construct a “caste” system to delineate the true artist from the fantastical escapist. (Aghhh! I swore to myself I wasn’t going to get snarky!)

Now you are probably asking, “Does this guy really believe that a simple painting of a red barn at some local art fair carries the same weight as the Mona Lisa?” (Hmmm, you are a tough crowd.) The truth is… (drumroll please) … I don’t have a clue. Let’s face it, today’s masterpieces may have been yesterday’s mad ravings. Consider Vincent Van Gogh, whose brother owned a successful art gallery and couldn’t traffic enough of his brother’s swirly creations for Vincent to afford a pumpkin spice latte. I can only say this, that these artists—Leonardo Da Vinci, Vincent Van Gogh, and the weekend painter—approached their subjects with the talent afforded them, through grace and hard work, and a passion for finding what is true, whether in the mysterious smile of a curious and iconic woman, the tortured and magnificent brush strokes of a starry night, or the isolation of a long ignored red barn. (Yes, it is possible to attribute meaning to most anything.)

So, just a warning here, as I step way out on this precarious limb and suggest that maybe this in-house bickering and battle for legitimacy comes from a need—for artists and those who live and love to discuss art—to feel worthy of their pursuit. Those of us who have dedicated our life to art in one way or another, want to feel that this irrational and often lonely enterprise—putting words to paper, paint to canvas, sound to tape—contributes in some practical way to humanity. After all, artists don’t build roads or cure diseases or unwrap the complex mysteries of the human genome. For artists, the planet Mars is merely a plot device or a landscape for a fictional Armageddon or part of a lyric, not an actual destination as it is for Elon Musk. Parents rarely urge their children to become painters, writers or musicians.

Most of my career was spent as a freelance commercial illustrator, a fairly practical pursuit, even if my profession is marred by dubious intent. But not everything I’ve created was for beer ads and ice cream packaging. (And please don’t hate me when I tell you I worked briefly, just briefly, on the Joe Camel campaign before he met his demise). So, please allow me to further validate my existence by telling you that I have designed over 100 commemorative stamps for the U.S. Postal Service. Over 100! Not convinced yet of my importance to society? Well, fifty of those designs were the Greetings from America stamps that (at the time nearly two decades ago) celebrated everything great about our nation! Still not swayed about my contribution? (Man, you really are a tough bunch!)

William Kowalski, author of Eddie’s Bastard and The Best Polish Restaurant in Buffalo, said of my new novel, The Cabin on Souder Hill, that it, “illustrates the power of the mind to overcome the dichotomy of what is rational and what is true.” Kowalski didn’t say it would save the world, or imbue our existence with meaning, or provide us the roadmap to world happiness (I’m not sure “world happiness” is even a thing). And though it would have been impossible for me to elucidate my own intent behind this novel, I could not have imagined a more poignant and eloquent assessment of the result. Like the painter of the red barn, I was drawing upon the skills afforded me, and trying to remain faithful to what I believed was true.

I suppose we could all take a clue from Houdini, who spent his life “escaping” self-imposed manacles and constraints, not in order to save humankind or imbue anyone’s life with meaning, and maybe not even to delight and shock audiences with his amazing illusions, but rather to rail against the boundaries of his own being, to sacrifice himself to the magic and awe of his existence.

*