Each day started with a brief meditation session where I would clear my mind and say to myself, “All that matters is the characters. Follow their lead, their needs and desires, and everything else about the narrative will unfold naturally.” As after all, in fiction, it truly is the characters who guide the story.

Let them lead and the story-arc will follow.

During my brief meditation, I would ask my characters what they were doing that day, how they were feeling, what they needed, and even if there was anywhere specific they wanted to go. Then I would kindly ask them to show up to set, so I could guide them on a wild and horrific adventure. And during this new ritual, I found something of vast importance—my authentic voice. In August 2020, I had the first draft of The Sommelier complete and for the first time in my life, the entire process felt like a wellspring of creativity and command as I purged my characters’ truth onto the page.

The experience was exhilarating.

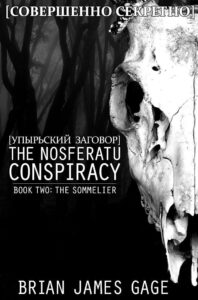

With the publication of The Sommelier, I’m now embarking on writing the third and final chapter of The Nosferatu Conspircay series. In doing so, I realized my approach isn’t specific to any one storyline or character, but envelopes a wider technique of how I have come to write supernatural historical fiction and horror.

Firstly, as all interesting fiction does, it starts with an inciting event. Luckily, we’re talking about history, so there are a slew of inciting events to choose from. Some cynics may cast this off as lazy and unimaginative, but I wholly disagree because within the constructs of a historical narrative are a wide variety of cracks and chasms to explore and situations to invent. And in many ways, it’s an even more creative process to break real world historical fact and rebuild it with pure fiction that feels authentic. The use of metaphor and subtext, a fictional narrative—specifically a supernatural historical tale—is primed to explore symbolism and parallels of modern times.

The goal is to write fictionalized history as if it were as real as what we were taught in history class, but bring it into the present by using the notion of fear to incense the reader’s emotions—reminding them through subtext that the monsters of the past can easily and readily explode into the present. These horrific beasts, although allegorical, still very much exist in the world today deep within the shadow elements of our own personalities.

Alma Katsu is one of the emerging masters of supernatural historical fiction, taking on the Titanic in The Deep, and the Donner Party excursion in The Hunger. And I think you’d be pressed to find more intriguing inciting events for the framework of supernatural history. For my inciting events, I chose the assassination of Grigori Rasputin and the Bolshevik Revolution for The Sleepwalker, and the Battle of Arras in WWI for The Sommelier.

Then comes the research.

It would be quite easy to get bogged down in every minute historical detail, reading tome after tome of nonfiction to ensure you had it all correct, but I don’t find that wise. What I’m after are the broad strokes, and from there my imagination can fill in the rest. The challenge being, it can become quite easy to offend or put off readers if you bend a historical fact they favor to fit into your fiction. For example, historically Rasputin first met the Russian royal family in 1905, but in The Sleepwalker they don’t cross paths until 1916 when my novel begins. A few readers were not pleased that I took this leap. This is where your judgment as an author comes in and you must decide what takes precedence—the narrative or the truth.

Hint: Choose the narrative.

But always try to stay as true to historical details as possible.

Which leads me to the most important component of creating authentic historical narratives—characterization. This is where you cannot cheat. The representations of the historical figures, I feel, must be as close to their real world personalities as possible. And although it looks impressive to have biography after biography of important historical figures lining your bookshelf, honestly—Wikipedia will do.

My novels feature a slew of historical figures and an equal amount of characters I invented for them to play with. The fictional characters are much easier as they can behave in any way you choose, so long as it aligns with their idiom as it were. Actual historical figures don’t have such a luxury. When merging real people into my narratives, especially if they’re in a starring role, I firstly like to look for specifics of what drives them. I feel any character, real or imagined, can be quickly characterized by understanding their desires and fears. For example, when researching Kaiser Wilhelm II for The Sommelier, I discovered he was born with a lame left limb.

Ah ha! My brain shouted.

I sat there for a long while thinking of all the grief and insecurity young Wilhelm must have endured in such a macho and rigid culture as the Prussian Empire—a time when men were to be bold, strong, and display not a shred of weakness. Don’t believe me? Check out their mustaches.

And yet here was Wilhelm—heir to the empire who couldn’t even throw a one-two punch, fire a rifle, properly chop wood, or wield a saber. It was his weakness. One that I envisioned he spent every waking hour of every waking day trying to overcompensate for. And that is the exact character you see in my book. He is overly cruel, demanding, and purposefully puts himself in harm’s way to demonstrate to his underlings that he is the strongest man in the German Empire—left arm be damned. My Wilhelm may be half a man in the eyes of Prussian machismo, but you’d be damned to ever challenge him on the matter. It’s as if every action he takes is to ensure nobody in his purview would dare mention his arm. All of the historical figures in my books are designed with the same characterization and attention to what scares them and what drives them.

When structuring your historical narratives, it is also vastly important is to understand the real-world settings, and specifically the architecture of the time as I think of the scenery and buildings as characters too, acting as monolithic prisons that our characters are confined to and must overcome, and it’s an eloquent way to include the subtext of person vs. their environment.

Then finally, well—there are the ghosts.

And that is where the fun begins. There are absolutely zero limitations as to what you can weave into the story. Be it vampires, sea serpents, or any form of monster you can dream up, from Lovecraftian to something yet to be envisioned by anyone.

There is truth in fiction. By using history and blending it with the supernatural, I find metaphor within paranormal fiction can reveal deep psychological fears and desires that drive us all, just as they do my fictional characters. What scares them may not scare you. There is a uniqueness to fear that is worthy of exploration. And oftentimes exploration requires the use of guides to navigate the rock. In this endeavor of human understanding, I believe those guides are myth, folklore, and metaphor. A vampire can be simply that, or underneath I can raise questions about what kind of monster is it that sucks the blood of decent, working-class people?

And that answer, gentle reader, I will leave for you to decide.

***