Crime fiction, which we might also call “homicide fiction,” has been popular since the 19th century, with the US and my native Britain dominating the genre. The trend continued even as violent crime rates generally declined and intentionally taking a life became an ever more unusual way for people to break the criminal law. In recent years, alongside invented mysteries and thrillers, we’ve seen the rise and rise of the true crime genre on streaming services and in audio podcasts. It appears everyone wants to know more about the minds of murderers.

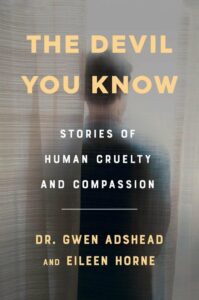

As it happens, this is my day job; I’ve spent the last 30 years working with violent offenders as a forensic psychiatrist and psychotherapist. I’ve recently joined forces with dramatist Eileen Horne to describe my experience in The Devil You Know: Stories of Human Cruelty and Compassion (Scribner). Our book is an invitation to come with me into sessions where I meet with people considered the worst among us. With 11 stories about men and women who have either killed or committed other serious crimes like stalking and sex offending, we try to fill the blank space after the Netflix or podcast credits roll, when the judge has passed sentence and the secure doors lock shut. What happens next? Can they be helped to change?

I’ve been an avid reader of crime fiction throughout my life, which sometimes surprises people who can’t help but wonder why I won’t leave all that at the office. I tell them that the best detective stories focus on restoring order to chaos, which I find relaxing and reassuring. Over the years, I’ve noticed that my patients have an interest in crime fiction too, although mainly in the form of dramas they watch together on TV. I remember one therapy group for homicide perpetrators particularly enjoying the American series Dexter, featuring a forensic professional who is secretly a serial killer. I am more ambivalent about viewing TV and films in the crime genre because they often dwell on the suffering of victims in ways I find gratuitous, and I get impatient when perpetrators are depicted as obviously weird, remarkable or preternaturally clever. As better minds than mine have defined it, evil is banal, even ordinary.

I grew up with the British greats of crime fiction who made an art form out of the ordinary, the masters and mistresses of the humdrum homicide. I have my mother to thank for fueling this at an early age; it was our weekly treat to walk down to the Barrington Street library to borrow books, stopping off to get some oysters from the fish and chip shop on the way home. It must have been she who recommended that I try reading Agatha Christie, whose works were among the first I chose. Of her characters, I’ve always liked Miss Marple best because she embodies the importance of being a good observer of human behavior.

Perhaps it was inevitable that when I qualified as a doctor and came to choose a branch of psychiatry, it would be forensic work that attracted me most. The word forensic derives from the Latin forum, meaning a place where disputes are heard or a court of law. My colleagues and I assess and manage people whose mental health issues lead to legal problems, which may land them in criminal or family court. In addition to giving expert testimony about people’s state of mind, we also care for that small number of people who have committed acts of violence while mentally unwell or offenders who have become mentally ill while in prison, which is more common. I gained an additional qualification as a psychotherapist when I realized that I wanted to focus on the human stories behind acts of serious violence.

Carl Jung once wrote to Freud that he felt “the reason for evil in the world is that people are unable to tell their stories;” I have seen firsthand that there is truth in this. The case stories I describe in our book explore my patients’ accounts of their lives and what they have taught me about our common humanity and capacity for both cruelty and compassion. It seems to me that the best crime writers have traveled the same path as they explore the ambiguities of good and evil.

I have heard it said of detective fiction, that “when you know why, you know who.” Finding that “why” is as important for me as for the crime writer inventing a story or for any real detective. Just as narrative causality is the engine of fiction, the “why” provides the basis for forensic approaches to murder trials. It is not enough for me to tell the court that a defendant had a recognized medical condition at the time of the killing. Their mental state must explain what happened, giving sense to the senseless. The jury is then free to accept or dismiss that story.

The “why” will influence a judgement in criminal court as to whether the defendant’s agency was diminished due to their mental state, which under British law would make them guilty of manslaughter instead of murder. After the trial, if they are convicted, their narrative may change in prison. One young woman I worked with, Kezia (who stabbed a care worker she thought was possessed by a demon) moves from thinking “My mental illness made me do it” to “When I was unwell, I thought I was in danger, but now I can see that I was wrong.” That is what success looks like for a forensic professional: an opening of the mind that can gradually lead a patient to take responsibility and move forward. One mind at a time, this makes the world a safer place.

A similarly ambitious mental shift is required of the psychotherapist. As a young trainee, I needed to rethink many preconceptions, some of which probably came from those mystery novels I’d grown up on. Despite the vast array of made-up murderers stalking through English country houses and quaint villages, the UK’s homicide rate today is around 700 per year in a population of 66 million. In the US (where the population is five times ours) the intentional homicide rate is about 18 times higher, but still nowhere near the roiling epidemic suggested by American crime novels, films, and television programs.

Studying the body of research into violent behavior, I would also find certain recurring risk factors had to align, like numbers in a bicycle lock, before someone committed a fatal act. These can include being young and male, in combination with things like substance abuse, social isolation, and previous criminal history. The final number which releases fatal violence will be idiosyncratic, possibly some innocuous action by a victim which has meaning only for the perpetrator. For some of my patients this may have taken the form of a simple greeting or a smile.

I learned early on that mental illness was not usually one of those “bike lock” risk factors. Despite ubiquitous ideas in our culture about crazed killers or mad sexual offenders, it is rare for anyone who is mentally ill to harm another person, let alone take a life– sadly, they are far more likely to be victims, and forensic psychiatrists will not assume that violence is evidence of mental disorder.

I recognize that writing crime fiction must be a daunting task, especially in a contemporary world where social media and mobile phones present dreadful plot problems, just as they do for real criminals. Who can disappear anymore? Who is undetectable in our time? When I sit with violent offenders in therapy, I am trying to discover with my patient what the function of their violence is for them. What problem do they think it solves in their life? I try to hold in mind that however terrible their offense, they are generally people with parents, friends, hopes and dreams; they were all children once, like any of us. In the most compelling crime writing, I’ve found that the author also allows us to consider the perpetrator’s whole of life story.

***