Black cut from white with a razor; a turned-down hatbrim; smoke lisping from a cigarette clinging to the corner of a lip; snappy, snarling dialogue; an ice princess as wicked as any fairy-tale witch; violence cast in shadow on an alley wall.

These images remain with you like the scarlet spot inside your eyelids when you squeeze them shut against a harsh light. They belong to a genre that is uniquely American, yet bears a French name: Film noir.

Shortly after France’s liberation from Nazi Germany during World War II, that country was inundated with American crime films that had been banned from importation for years. Taken all in a lump—a blitz—these movies showed a sudden, stark contrast between the rags-to-riches-to-dusty death morality tale of the gangster film and an ambiguous world in which good and bad intertwined in a gray area in which, often as not, virtue went unrewarded and vice reigned supreme—at least for all but the last five minutes before the credits rolled. It was in that moment that the French cineastes gave the movement its name: in English, “black film.”

Its dark philosophy resonated with an audience disillusioned by corruption in high places, appeasement with evil, and a way of life altered forever.

From this primordial swamp emerged a new species of star: Humphrey Bogart, the cynical isolationist, Robert Mitchum, the resigned pessimist, Claire Trevor, Lizbeth Scott, Gloria Grahame, Marie Windsor, Ann Savage, the black widows bent on survival at any cost, no matter who perished in its attainment. Their world thrived in darkness, withered in sunlight. Bleak as it was, this world, it beckoned. Little else in a world marinated in war, Prohibition, and Depression dared to offer anything so close to the truth.

Mitchum: “I think I’m in a frame. . . . I’m going up to get a look at the picture.” Isn’t that what we all want? We sure won’t get it from Shirley Temple.

History travels on a continuous loop. Vietnam, political assassination, Watergate, 9/11, and now the Coronavirus have plunged us all into that post-Edwardian world of fear, uncertainty, and lack of faith in the Establishment. Just as Americans did at the time of the Revolution, we’ve learned to turn to the Outsider to lead us to victory: The Minuteman, the cowboy, the private detective operate both inside and outside the law, passing between the worlds of the criminal and the policeman, and wresting from the struggle something that may not be justice or mercy, but will pass for them in lieu of the impossible ideal.

It began with literature considered trash in its time: the ten-cent pulp magazines and the two-bit paperback novels that gave voice to Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Erle Stanley Gardner, Ross Macdonald, John D. MacDonald, and Mickey Spillane. As with all things American—the western, jazz, rock and roll—the New World’s major contribution to art began in the gutter, and there it remains: shouting up to the penthouse through cupped hands, gat in hand and with only a battered fedora and a soiled trenchcoat between it and the elements of cruel society.

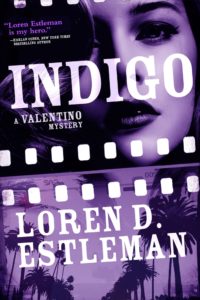

I’d been waiting to pay my personal tribute to noir ever since I began the Valentino, film detective, series in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine twenty-two years ago. The process of rebooting it in book form contributed to that delay, but the wait was worth it. Leavened with humor, but faithful to the psychological suspense and characterizations of the form, Indigo is my love letter to the best in our native cinema. I hope the shades of those who crafted it so many years ago will approve.

Some moviegoers—and I’m one of them—will on occasion slake our thirst for sweetness and light with The Sound of Music; who can resist Julie Andrews shouting joy from an alpine mountaintop (out of earshot of Hitler)? The rest—and I am most assuredly one of them—will wallow ourselves more often in Out of the Past, reveling in Jane Greer’s psychopathic glee—and emerge just as refreshed.

That’s film noir. Its effect on the human experience is as difficult to define as the genre itself. All I can offer in the way of explanation is to urge you to watch it. As it is with all real art, you will come away from it changed.