Last year, during a radio interview about my novel that had been released in April, the show’s host commented that thrillers all seem to have three elements: a car chase, blood, and naked bodies. “Does The Fourth Courier have all of those?” he asked.

I said it did with the caveat that the car could only putt-putt along, so the scene didn’t exactly qualify as a car chase.

Then he wanted to know, “What’s in your story for women? It sounds so masculine.”

I appreciated the question because I had asked it myself, though not because of the generalization that thriller is a male genre—because it no longer is. The distinctions between thrillers, murder mysteries and general crime fiction are so blurred as to sometimes be arbitrary. Murder mysteries by definition involve a murder, but there are cozy mysteries and more violent ones that can just as easily be described as thrillers. When they get lumped together, it turns out that twice as many women read crime novels as men.

It certainly didn’t start out that way when thrillers truly were aimed at male readers. The first thriller is commonly regarded to be Erskine Childers’s The Riddle of the Sands published in 1903, in which there were no female characters until the publisher convinced the author to include one, and then she had only a minor role. That remained true about thrillers for decades: women largely had only minor roles, and more often than not, they were the victims of a story’s violence: murder, rape, or some other violation. Or they were cast as femmes fatales: dangerous, conniving, lethal. Male protagonists, on the other hand, were idealized as being able to fend off physical danger, even as the threats mounted and exploded into violence.

Thrillers truly were a male domain written by, for, and about men until 1978 when Ken Follett published The Eye of the Needle, the first thriller to have a female protagonist. It opened the door for thrillers to have more than minor female characters, and for those characters to be just as tough, reliable, intelligent, and have the same sense of agency that readers had come to expect of their male counterparts.

Appealing to women readers has its clear marketing advantages, though accurately calculating that advantage is tricky. It’s generally agreed that an estimated 80 percent of fiction books sold in the US, UK and Canada are purchased by women. (They aren’t, of course, necessarily buying them only for themselves.) Other sources say that women and men read in about equal percentages, but on average, women read nine books per year versus five for men. One survey says women read more than men in all genres except history and biography; another says it’s men who read the most fantasy, science fiction and horror—but in both cases, it appears women are reading thrillers on par with men. The writers of thrillers and mysteries (which are often lumped together) are about equally divided between men and women.

So back to the radio host and his question, what about my thrillers appeals especially to women readers?

I never set out to write thrillers per se, a genre that’s typically driven more by action than character development. I want to write novels that have both. Also, I want my books to be more than a thrilling read. I want to enlighten my readers as well as entertain them. So I take a suspenseful situation or threat that reflects some larger issue, and show how that situation affects the lives of ordinary people and families. My first novel, A Vision of Angels, managed to do that, and it’s been a model of sorts for my work ever since.

A Vision of Angels is a story I felt so compelled to write that I quit a career in international development to become a full-time writer. Naively, I believed it might actually contribute to Middle East peace! I had grown up a Zionist (though I’m not Jewish) and ended my career assisting Palestinians as part of the peace process. I understood and appreciated the many sides of that conflict, and felt compelled to write about it. In the novel, a planned terrorist attack interweaves the lives of four characters and their families—an American journalist, Israeli war hero, Palestinian farmer, and Arab-Christian grocer—in a story thematically about reconciliation that becomes clear through a memory shared by an old Jewish man at a seder dinner. (Here’s a link to that excerpt (edited to be a monologue.)

My emphasis on how ordinary people respond to the extraordinary circumstances of a crime or threat appears to strike a chord with women readers. While there is always something suspenseful at the heart of my stories, they are less about heroism and more about emotional content. They aren’t lone wolf tales in fabricated set-ups, but stories about real people suddenly endangered in their daily lives.

***

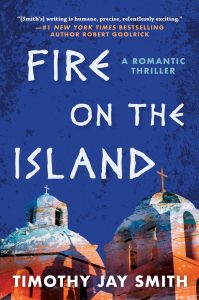

I’ve never written a female main character. That said, I’ve plenty of strong women in my books, perhaps best exemplified by my latest release, Fire on the Island, set in Greece. In it, an island village grapples with declining tourism, refugees, and family feuds, when an arsonist threatens to burn down the whole place. The FBI agent posted to Athens is sent to investigate and finds himself in the midst of a village rife with conflicts that are gradually revealed to him through three generations of women in one family.

On the other hand, all of my novels have gay male protagonists, and surprisingly, that appeals to women readers in a couple of unexpected ways. The first is the sex itself (and I don’t write erotica but sex scenes that are suggestively sensual). Until I was helping my publicist market my last novel, which has a black gay CIA agent as its real hero, I had no idea there was something called M/M romance (translated: Man/Man sex), and would never have guessed it would be largely the purview of straight women. There’s a huge demand for it, it’s simply enormous, and in my experience, 99% of M/M bloggers and website administrators are not gay and are not men. So where I was reluctant in some circumstances to emphasize the homosexuality in my stories, I now realize, it’s more an asset than a detraction.

The world of thrillers is still largely uninhabited by gays, though that’s changing thanks to the writers like John Copenhaver, Michael Nava, Neil Plakcy, and Christopher Bollen (to name a very few). Having gay protagonists is also a way to push back at the genre’s stereotype, which is so prone to gratuitous violence against women that, three years ago, the international Staunch Book Prize was launched “for thrillers in which no woman is beaten, stalked, sexually exploited, raped or murdered.” I know it happens that self-loathing gay men have, in novels, raped women to prove something about their masculinity, but that’s a very rare story. Instead, for my readers at least, they appreciate that brains matter more than brawn, and women are portrayed as more than sexual conquests, which makes more room for clever and engaging stories.

*