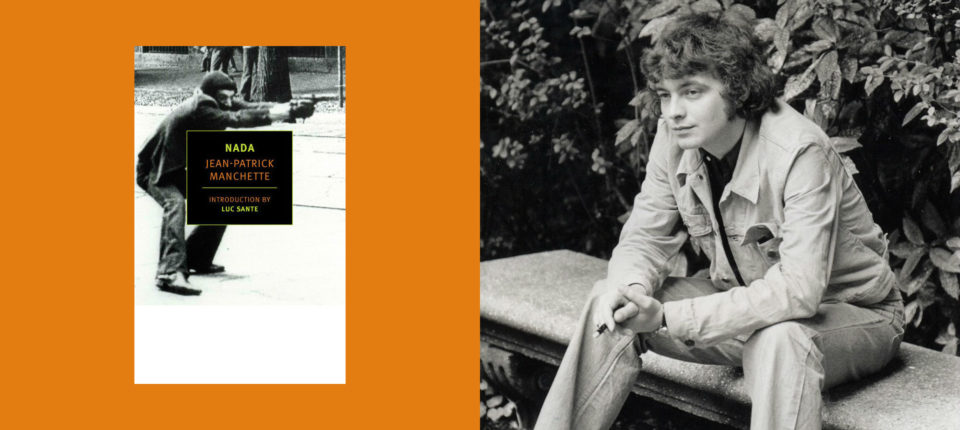

Nada, first published in November 1972, was the fourth novel by Jean-Patrick Manchette, not counting pseudonymous titles, novelizations of films, and other products of what he called “industrial” writing. He was twenty-nine and a seasoned Grub Street professional, and he was fully aware of the political currents of his time. He had joined Communist youth organizations a decade earlier and demonstrated in favor of the liberation of Algeria; more recently he had come under the influence of the Situationist International. It was natural, especially in the highly politicized cultural climate of post-’68 France, that he should merge his two reigning passions and begin writing thrillers on political themes. The first novel he wrote under his own name, L’Affaire N’Gustro (1971), was based on the kidnapping and disappearance of the Moroccan opposition leader Mehdi Ben Barka in Paris in 1965.

Nada is also about a kidnapping—of the U.S. ambassador to France by a ragtag bunch known as the Nada group, led by professional revolutionaries. The book is structured like a classic caper novel by Frédéric Dard or Albert Simonin. American readers, encountering it in Donald Nicholson-Smith’s crisp and astute translation, might consider it a cousin to the novels that Donald Westlake (whom Manchette admired and translated) wrote under the pseudonym Richard Stark, most of which involve capers gone wrong; like them it is dry and tight, and the pages fly by as if the reader were watching a movie. The caper format is here adapted to the single most newsworthy leftist-terrorist scenario of the 1970s: the symbolic abduction. The casual reader, unburdened by dates, might think that Nada was inspired by the kidnapping of Hanns Martin Schleyer by the Red Army Faction in Germany, or that of Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades in Italy, but those events would not occur until 1977 and 1978, respectively.

Nada was written early in the period that became known in Europe as the Years of Lead, a time when revolutionary fervor was cresting, as was frustration at the glacial if not retrograde pace of social change. The urge to action was felt everywhere, although it primarily resulted in meetings and pamphlets. But the Red Brigades carried out their first kidnapping in 1972—the twenty-minute abduction of a factory foreman—and the Red Army Faction also undertook a bombing campaign that year: four incidents, five dead, fifty-four injured. (The French counterparts of these groups, notably Action Directe, would not be formed for several more years.) Manchette recorded in his diary that on May 7, as he was finishing the manuscript, his wife (and frequent collaborator), Mélissa Manchette, suggested that his characters might be “positive models,” to which he responded: “Politically, they are a public hazard, a true catastrophe for the revolutionary movement. The collapse of leftism into terrorism is the collapse of the revolution into spectacle.”

The characters in the gang are the usual odd mix you expect to find in caper novels. Buenaventura Diaz is one sort of professional revolutionary, an exile who never met his father—he died in 1937 defending the Barcelona Commune—and who has invested his whole life in militant action; his only other significant interest is gambling at cards. In Claude Chabrol’s uneven 1974 film adaptation he is given the full spaghetti-western romantic treatment. André Épaulard is a professional of another sort, a former member of the Communist Resistance during the Occupation who has never been able to quench his thirst for action, and while pursuing revolutionary opportunities around the world has also dabbled in corruption. Manchette enjoys endowing his characters with Homeric epithets; Épaulard is usually “the fifty-year-old” or “the ex-FTP fighter,” referring to the “Francs-Tireurs et Partisans” in the Resistance. His name implies that he is given to shouldering his way through. In his review of Chabrol’s film, Andrew Sarris noted that the character’s essence combines Humphrey Bogart’s “wrinkled fatalism” and Yves Montand’s “wistful patience.”

Marcel Treuffais, who teaches philosophy at a suburban lycée, is the author of the Nada manifesto, their resident intellectual, a proud member of the Libertarian Association of the Fifteenth Arrondissement (Errico Malatesta Group). In keeping with genre conventions, there is also muscle: the driver, D’Arcy, a drunk (he is invariably referred to as “the alcoholic”); and Meyer, a waiter who has a crazy wife, seems to have gotten involved with the group for no particular reason, and doesn’t do much (“Meyer, who hardly ever said anything”). There is also an unofficial sixth member, Véronique Cash, the group member who provides the farm they use as a hideout, who proves to be as ferocious a fighter as Diaz and much more so than Épaulard. As she tells the latter: “My cool and chic exterior hides the wild flames of a burning hatred for a techno-bureaucratic capitalism whose cunt looks like a funeral urn and whose mug looks like a prick.”

Manchette is as ever rich in details; as always, he flaunts his encyclopedic knowledge of guns and cars. And he is sharp in his satire of both the faction-intensive Parisian left of the time and the labyrinthine corridors of the government and the police. Few thrillers have been stuffed with quite as many acronyms as this one. It is telling that a major plot turn occurs as a result of an obscure squabble between two law-enforcement agencies. For that matter, every action and statement by the gang is followed by retorts and denunciations by the variegated leftist groupuscules, which are duly noted by Le Monde in a sidebar. An entity calling itself the New Red Army dismisses them as “petty-bourgeois nihilists” and proclaims:

“Down with All Little Neumanns!”

“Neumann? You mean like Alfred E. Neuman?” asked Épaulard in alarm.

“Heinz Neumann,” Cash clarified, placing the tray and radio on the table. “A guy who had something to do with the Canton Commune in December 1927.”

From its tower Le Monde parses their manifesto: “The style is disgusting . . . and the childishness of certain statements of an archaic and unalloyed anarchism might raise a smile in other circumstances.” TREMBLE RICH PEOPLE YOUR PARIS IS SURROUNDED WE ARE GOING TO BURN IT DOWN says a wall, echoing the telegrams sent from the occupied Sorbonne to the Communist Parties of China and the USSR during May ’68: SHAKE IN YOUR SHOES BUREAUCRATS STOP THE INTERNATIONAL POWER OF THE WORKERS COUNCILS WILL SOON WIPE YOU OUT STOP. . . . Meanwhile a member of the ambassador’s protective detail is reading Ramparts and the other The Greening of America by Charles Reich.

The book is briskly paced, full of clipped dialogue and nonstop action, but it also presents a political argument. Treuffais, who seems to be something of an authorial proxy, decides not to go along with the plot, for doctrinal reasons: “Terrorism is only justified when revolutionaries have no other means of expressing themselves and when the masses support them.” By the end, Diaz, who had kicked Treuffais out of his apartment when the teacher begged o, has come to agree with him. “Leftist terrorism and State terrorism, even if their motivations cannot be compared, are the two jaws of . . . the same mug’s game,” he admits. “The desperado is a commodity.” Manchette has the press dub the gang’s hideout “the tragic farmhouse”—the epithet used by the newspapers in 1912 to refer to the death scene of Jules Bonnot, the driver and press-appointed leader of the Bonnot Gang, an earlier model of that commodity. Sixteen years after its French publication, in his preface to the book’s first Spanish edition, Manchette acknowledged that its political argument was “insouciant and obsolete,” because it “isolated” the gang from the broader oppositional social movement, and furthermore failed to account for the “direct manipulation” to which the State would have subjected such a group.

But whatever its theoretical shortcomings, Nada is a remarkable book. At the time of its publication, there was nothing like it outside of Manchette’s work; novels and politics kept separate bedrooms. As Didier Daeninckx, who began writing his political thrillers in the 1980s, put it in an interview: “Manchette seized a scorned genre that in the 1960s was right-wing, even extreme right-wing, and in one stroke shattered the conventions. With that he effected a split in the genre.” Manchette essentially launched an industry of left-wing thrillers, ranging from a historically minded stylist such as Daeninckx to the brew of crime, porn, and agitprop served up by Éditions de la Brigandine in their quickies, which are bylined with various noms de guerre and intended to lure the innocent consumer of pulp. Manchette himself would go on to produce six more novels in the course of the 1970s, each seemingly more complex and considered than the one before. But Nada was his first real hit, as in a hit song, striking an unexpected chord that resonated with the French reading public, and like a true hit it has carried on, bringing the baggage of its time into our own very different set of circumstances without losing any of its power.