“Money, you think, is the sole motive to pains and hazard, deception and deviltry in this world. How much money did the devil make by gulling Eve?”

–Herman Melville, The Confidence-Man

The main character of my new novel, The Smack, is Rowan Petty, a down-on-his-luck con artist who finds out about two million dollars in stolen Army money stashed in a Los Angeles apartment and decides to steal it. I’d been wanting to write about a grifter for a while, and when I read an article about a crew of soldiers smuggling money out of Afghanistan, I decided Rowan would be the perfect “in” to that story.

I’ve long been fascinated by confidence artists and the scams they run. On one level it’s the process that interests me, the nuts and bolts of the cons, how they’re planned and pulled off. There’s also the psychological aspect, both of the grifter and the victims. In the majority of cons, those who are taken in by a scam know that they‘re falling for something that’s too good to be true, but greed and magical thinking get the better of them.

As for the people running the cons, I love the notion of them setting themselves apart from straight society, the common rabble of losers, lames and chumps. They see themselves as smarter than the average Joe or Jane and assume the bearing of criminal royalty. Great stuff for a fiction writer interested in extreme characters.

Below are three films and two books I revisited in the course of writing The Smack in order to immerse myself in the world of con artists and in an attempt to understand the ins and outs of a subculture that gleefully and ravenously exploits the moral failings of their fellow men and women. Watch the movies, read the books, and maybe you won’t get taken in if you should ever cross paths with a hustler on the make. And remember: You can’t cheat an honest man—so keep it honest, people!

Herman Melville, The Confidence-Man (1857)

A mysterious mute boards a Mississippi steamboat on April Fool’s Day and proceeds to scrawl proclamations about charity on a chalkboard he carries with him, much to the consternation of his fellow passengers, most of whom are grifters of one sort or another. We are then treated to a series of sketches involving these scalawags, who try to swindle one another and engage in wily discourses on gullibility and skepticism. Later, we listen in on philosophical conversations that Frank Goodman, “the cosmopolitan,” has with his fellow travelers.

Allegory? Satire? Parable? An exposé of the dishonesty at the heart of the American psyche? The Confidence-Man is all of these and more, according to the experts. The fact that some scholars peg Goodman as Satan and others see him as Jesus Christ indicates how much room there is for interpretation, but I enjoyed the book on a purely visceral level as an amusing portrait of mid-19th-century bamboozlers attempting to do each other dirty. Melville meant to entertain here, and he does, so don’t be frightened off by the reams of critical analysis surrounding the book. If, however, you wish to delve deeper, my edition was fully annotated and had an extensive bibliography that’ll help you examine this odd and endearing little novel from every angle.

David W. Maurer, The Big Con (1940)

This is the classic study of the con games and con men of the early 20th century. The scams laid out here range from those as basic as using loaded or shaved dice in a crap game to complex long cons that involved setting up fake gaming clubs populated by paid shills and transmitting phony race or fight results. It’s also filled with great anecdotes like this one: “A good grifter never misses a chance to get something for nothing, which is one of the reasons why a good grifter is often also a good mark. Indiana Harry, the Hashhouse Kid, Scotty, and Hoosier Harry were returning to America on the Titanic when it sank. They were all saved. After the rescue, they all not only put in maximum claims for lost baggage, but collected the names of dead passengers for their friends, so that they too could put in claims.”

The book is a must-read for the monikers and lingo alone. It’s populated by characters like the Yellow Kid, the Punk Kid, Fred the Florist, and Limehouse Chappie, who call banks “jugs,” nosey bastards “ear-wiggers,” and pickpockets “cannons.” The extensive glossary will have you cracking wise like a C-gee in a big store in no time. And while some of the methodology behind these old-school scams is dated, new variations are still rooking the greedy and the gullible to this day.

Paper Moon (1973), directed by Peter Bogdanovich

A grifter named Moses Pray meets his nine-year-old daughter Addie for the first time at her mother’s funeral. Moses agrees to deliver the girl to her aunt in St. Joseph, MO, and the two embark on a picaresque journey across Depression-era Kansas and Missouri, pulling a variety of scams along the way. The film is shot in gorgeous black and white by Lazlo Kovacs and features a great performance by Ryan O’Neal as Moses and an astonishing one by O’Neal’s daughter Tatum as Addie. The film is funny and sad at the same time, a true classic.

The main hustle in the film, sometimes known as “The Obituary Fiddle,” involves scanning the obituaries for the names of recently deceased men, inscribing a Bible with a widow’s name, then attempting to “deliver” the Bible to the widow, claiming that her late husband had ordered it for her and still owes money on it. Another hustle is a short-change scam called “Change Rising.” It’s too complicated to explain, so here’s a link to a scene in the movie where Moses pulls it off. People tried this one on me a few times when I worked in a supermarket, but I caught on quickly thanks to this film.

The Sting (1973), directed by George Roy Hill

This fast and funny film stars Paul Newman and Robert Redford as a couple of con men trying to get revenge on a mob boss in 1936 Chicago. I remember the main song from the soundtrack, the ragtime tune “The Entertainer,” by Scott Joplin, being all over the radio after this came out. I also remember being totally taken in and delighted by the scams in the film.

It opens with a “pigeon drop,” which is a hustle in which you convince someone to give you some of their money on the promise that they’ll receive a much larger sum later. Here’s a clip of how it went down in the movie. The main scam in the film is a variation on one of the most elaborate cons ever invented, “The Big Store.” Step one is to set up a phony gambling establishment. Step two is to people it with paid staff and customers (shills), and step three is to use this setup to take off a big-money mark. In the film, the con involves phony horse racing results. It’s a bit hard to follow, but all the clues are there if you’re paying attention. It ends with a “cackle bladder” gag. Consult Maurer’s book for the definition of that and also a detailed breakdown of the history and development of “The Big Store.”

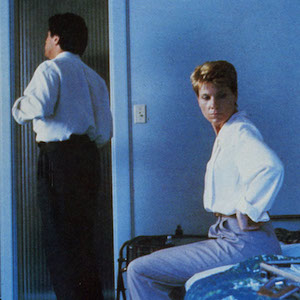

House of Games (1987), directed by David Mamet

Nobody writes about con artists as well as David Mamet. American Buffalo, Glengarry Glenn Ross, and The Spanish Prisoner are all deep dives into the world of hustlers on the make, but his film directorial debut, House of Games, is perhaps the most insightful of his works when it comes to scammers, marks, and the psychological forces at play in the relationship between them.

A psychiatrist, Margaret Ford (Lindsay Crouse) falls for a grifter named Mike (Joe Mantegna) and ends up involved in a scam with him. The whole film is a kind of long con, so I won’t go into more detail than that in order to avoid spoilers. I can say that in the course of the film, various types of short and long cons are pulled off and explained, and anybody looking for a crash course in hustles will get it here. Here’s a scene where Mike explains a classic short con to Margaret (and, yes, that’s a very young William H. Macy as the Marine).

__________________________________

Richard Lange’s latest, The Smack, is available now from Mulholland.